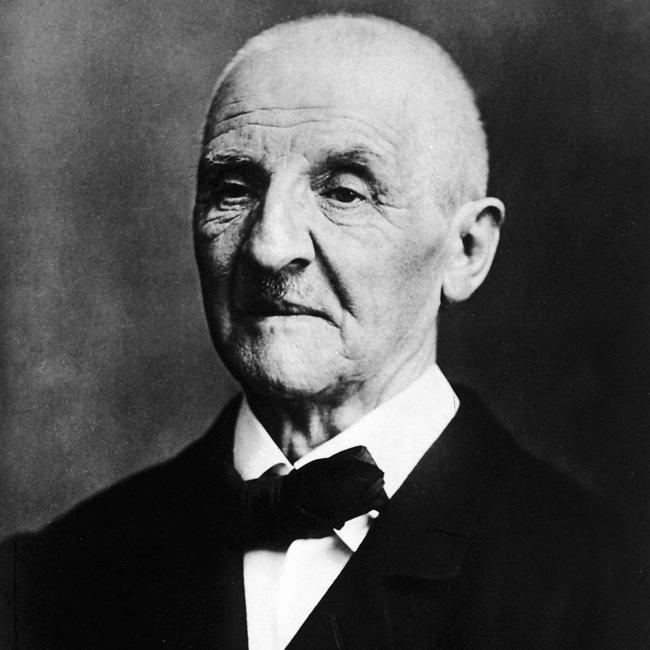

Bruckner

Born: 1824

Died: 1896

Anton Bruckner

Bruckner’s reputation rests almost entirely with his symphonies – the symphonies, someone said, that Wagner never wrote.

Discover Bruckner's life and music...

Symphonies Nos 0 & 00

Marcus Bosch on two works that reveal Bruckner’s emerging symphonic voice – inspired by Mendelssohn

➤ Bruckner’s Symphonies 0 & 00, an introduction by Marcus Bosch

Symphony No 1

Gerd Schaller on the immediacy and philosophical nature of the composer’s first numbered symphony

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 1, an introduction by Gerd Schaller

Symphony No 2

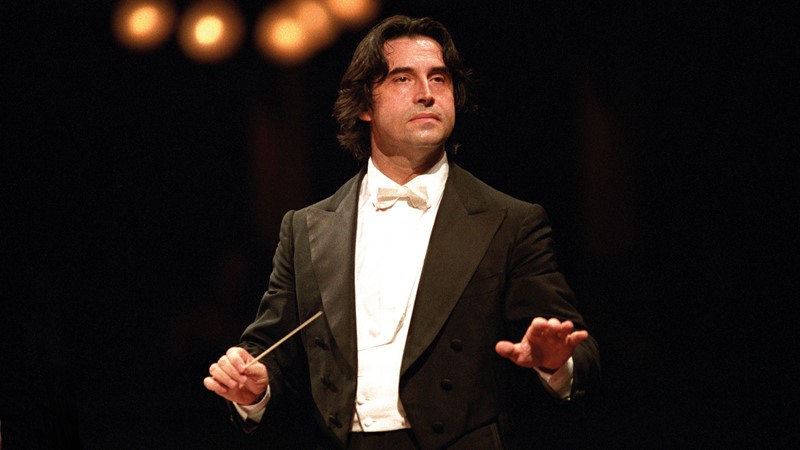

Riccardo Muti finds that this, like all of Bruckner’s symphonies, carries a message for the soul

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 2, an introduction by Riccardo Muti

Symphony No 3

Markus Poschner seeks the truth behind this early symphony

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 3, an introduction by Markus Poschner

Symphony No 4

François-Xavier Roth on a work whose different – and very unique – versions inform one another

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 4, an introduction by François-Xavier Roth

Symphony No 5

Christian Thielemann discusses this accessible work which exudes a positive energy

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 5, an introduction by Christian Thielemann

Symphony No 6

Simone Young on why this emotionally charged symphony is her favourite by this composer

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 6, an introduction by Simone Young

Symphony No 7

Lahav Shani on the lyricism of this work and the human emotion it conveys

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 7, an introduction by Lahav Shani

Symphony No 8

Herbert Blomstedt considers a work that’s nothing short of miraculous

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 8, an introduction by Herbert Blomstedt

Symphony No 9

Andris Nelsons on a symphony he places alongside the mighty ninths of Beethoven and Mahler

➤ Bruckner's Symphony No 9, an introduction by Andris Nelsons

Top 10 Bruckner recordings

A beginner's guide to the music of one of the great symphonic composers... Read more

Bruckner Redrawn

The view of Bruckner’s symphonies as vast musical statements is challenged by a ‘miniaturised’ version of the Second by Antony Payne. This ‘bare-boned Bruckner’ raises wider questions about the composer’s intentions, writes Philip Clark... Read more

‘I never had a more serious pupil than you,’ remarked Bruckner’s renowned teacher of counterpoint, Simon Sechter. Certainly, no one could ever accuse Bruckner of being frivolous and quite how this unsophisticated, obsequious boor came to write nine symphonies of such originality and epic splendour is one of music’s contradictions. You don’t turn to Bruckner the man or the musician for the light touch. His worship of Wagner verged on the neurotic for, really, there is something worrying about his debasement before the composer of Tristan. The dedication of his Third Symphony to Wagner reads: ‘To the eminent Excellency Richard Wagner the Unattainable, World-Famous, and Exalted Master of Poetry and Music, in Deepest Reverence Dedicated by Anton Bruckner’; before the two men eventually met, Bruckner would sit and stare at his idol in silent admiration, and after hearing Parsifal for the first time, fell on his knees in front of Wagner crying, ‘Master – I worship you’. His soliciting of honours, his craving for recognition and lack of self-confidence, allied with an unprepossessing appearance and a predilection for unattainable young girls, paints a disagreeable picture. The reverse of the coin is that of the humble peasant ill at ease in society, devoutly religious (most of his works were inscribed ‘Omnia ad majorem Dei gloriam’) and a personality of almost childlike simplicity and ingenuousness. God, Wagner and Music were his three deities.

He was the son of a village schoolmaster whose duties included playing the organ in church and teaching music. When his father died in 1837, Bruckner enrolled as a chorister in the secluded monastery of St Florian where he studied organ, piano, violin and theory. The story of his life until he was 40 was one of continual study, with an income derived from various meagre teaching and organ posts. Few major composers have waited so long before finding their voice. He was 31 when he began studying with Sechter in Vienna and remained with him on and off until 1861. His lack of confidence in his abilities as a composer led him onwards to more extended studies (this time of Italian and German polyphony – especially Bach) until, like Saul on the road to Damascus, the blinding light of Wagner hit him when he attended the first performance of Tristan und Isolde in Munich in 1865. All these rules and theories he had been assiduously absorbing had to be abandoned – for that was what Wagner had done.

The year 1868 saw the arrival of his first important works, though one of them, the Mass in F minor, had been prefaced by depression and a nervous breakdown which included a spell of numeromania – an obsession with counting. But if Wagner’s music had opened the door, it also put obstacles in the way of recognition. There was indecently fierce opposition to Wagner and all his works in Vienna (orchestrated by the influential critic Eduard Hanslick, whom Wagner caricatured as Beckmesser in his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg). Anyone who was so clearly under the influence of Wagner was also the subject of attack and Bruckner’s Third Symphony was greeted with catcalls from the anti-Wagner pro-Brahms faction of the audience at the premiere. Few people remained in the hall to applaud. The Fourth Symphony, given in Vienna under the great conductor Hans Richter, was better received and later Richter recalled the pathetic gesture of thanks that the tearfully thankful composer made after the first performance. ‘Take it!’ Bruckner said, squeezing a gulden into Richter’s hand. ‘Drink a pitcher of beer to my health.’ Richter wore the coin on his watch chain for the rest of his life ‘as a memento of the day on which I wept’.

In 1884 the tide turned. After conducting the premiere of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, the charismatic Arthur Nikisch wrote, ‘Since Beethoven there had been nothing that could even approach it’. During the last 35 years of his life, Bruckner combined composition with teaching and held a number of prestigious appointments in Vienna, at the Conservatoire, the University and St Anna College.

Throughout his life Bruckner searched for a woman with whom to share his life. He was 43 when he fell in love with a 17-year-old, whose parents put a stop to the relationship. He fell for another 17-year-old in his mid-fifties. Though the parents in this instance gave the relationship their blessing, the young girl tired of Bruckner and his passionate letters went unanswered. Later still he became infatuated with the 14-year-old daughter of his first love – that came to nothing and at 70 he proposed to a young chambermaid. Her refusal to convert to Catholicism ended that. Piety and pubescent girls are not an attractive combination. Bruckner died a virgin and was buried under the organ at St Florian.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.