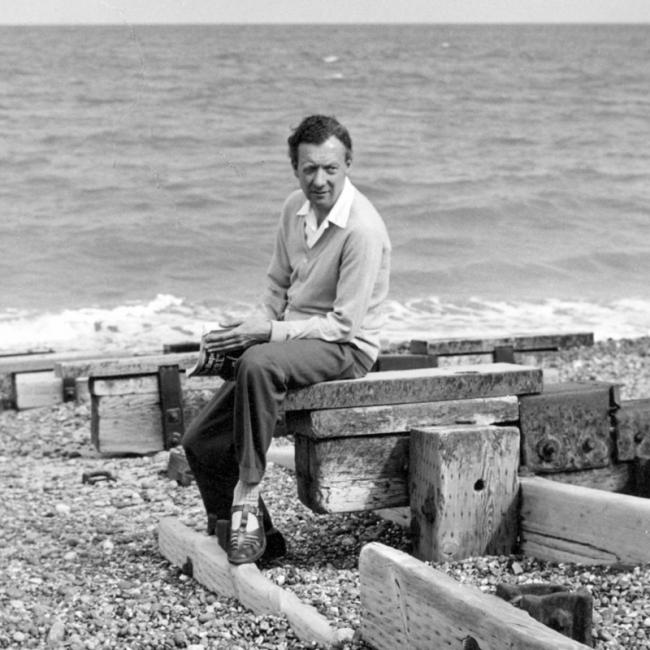

Britten

Born: 1913

Died: 1976

Benjamin Britten

Britten came of age in 1934, the year in which Elgar, Holst and Delius died. He rapidly dragged British music into another era – his own.

Explore Britten's life and music...

Benjamin Britten's first Gramophone review

by Alec Robertson (September 1938)... Read more

Benjamin Britten interview

The composer speaks to Alan Blyth (June 1970)... Read more

Britten in America

In 1939, Britten fled to the US where, for a time, he house-shared with fellow musicians, writers and a burlesque dancer, as Philip Clark reveals... Read more

England’s most significant composer in the second half of the 20th century was born on St Cecilia’s Day (November 22). The patron saint of music blessed Britten with precocious gifts for he began playing the piano at two and was reading symphony and opera scores in bed at the age of seven. By his 10th birthday he had completed an oratorio and a string quartet; by 16 he had produced a symphony, six quartets, 10 piano sonatas and other smaller works. Some of the material from these juvenile works was later incorporated into one of his first mature works, the Simple Symphony (1934).

Britten was the son of a dental surgeon and a mother who was a fair amateur pianist. He had a good education, adding the viola to his sporting and musical accomplishments at school before studying with the major influence on his musical development, Frank Bridge. Later, at the Royal College of Music, John Ireland was his composition teacher; Arthur Benjamin (of Jamaica Rumba fame) taught him piano. Britten’s unique voice was quick in arriving and soon after completing his studies he was commissioned to write the music for a number of innovative documentary films, most notably Night Mail for the GPO film unit. In this he collaborated with the second figure who was to influence his thinking, the poet WH Auden.

Not only did Auden provide the text for Britten’s first song-cycle (On this Island) and reveal to him the beauties of poetry and awareness of the possibilities of setting words and music, but he enforced Britten’s pacifist convictions. When Auden departed for America in 1939, Britten and his friend, tenor Peter Pears, followed him a few months later feeling, in his own words, ‘muddled, fed-up and looking for work, longing to be used’. Before this, the first performances of the Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge had taken place at the Salzburg Festival (1937) and in London. Aaron Copland reviewed it: ‘The piece is what we would call a knock-out.’ Not yet 30, Britten was firmly on his way.

While in America he produced his first big orchestral work (Sinfonia da Requiem, 1940) and his first dramatic work, the operetta Paul Bunyan, which was – as Britten put it – ‘politely spat at’. In 1942, with the war going badly for Britain and feeling homesick, he decided to return home. He appeared before the Tribunal of Conscientious Objectors and was exempted from military duty, prepared to do what he could for the war effort without sacrificing his pacifist ideals. He was allowed to continue composing as long as he took part in concerts promoted by CEMA (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts). Britten, apart from being a fine and exacting conductor of his own works, was always an excellent pianist (he was the soloist in the premiere of his Piano Concerto in 1939). His Mozart-playing was exquisite but as an accompanist in recital or as a chamber musician he was up there among the best.

Before the end of the war he had produced two of his most enduring works, the Ceremony of Carols and the Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, but it was his opera Peter Grimes that made him internationally famous. This was the result of a commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation in America. The resumption of artistic activity after the conflict and the reopening of the Sadler’s Wells theatre made this a keenly anticipated event and produced one of the most memorable first nights in British music. Peter Grimes was hailed as milestone in modern opera.

With only two opera companies established in Britain, Britten founded the English Opera Group. Then in 1948 he, with Eric Crozier and Peter Pears, founded the Aldeburgh Festival, then, as now, an indispensable national flagship of musical excellence. He and Pears had made their base in the Suffolk village and it was remain their home for the rest of their lives together. A string of operas followed Peter Grimes, some with the expected full orchestra, some scored for a mere 12 instruments, facilitating performances and showing the composer to be a master of inventiveness with limited forces. The Rape of Lucretia (1946), Albert Herring, Billy Budd, The Turn of the Screw, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Death in Venice (1973) have all, to a lesser or greater degree, established themselves in the repertoires of opera houses the world over.

Britten was particularly adept at writing music for children, accessible without being condescending, and works like Let’s Make an Opera, Noye’s Fludde and The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra have had a stimulating, not to say inspirational, effect on generations of young people. In 1961 he received a commission to celebrate the consecration of the newly built Coventry Cathedral to replace the building bombed in the war. The result was his powerful and profound War Requiem, using the words of the Latin Mass and the poems of the First World War poet Wilfred Owen.

In 1967 the tiny Jubilee Hall in Aldeburgh was replaced by the conversion of part of The Maltings at Snape into a larger concert and opera hall. Two years later it was destroyed by fire. The phoenix which rose from the ashes has proved to be among the outstanding concert halls of Europe and it was here that the first performance of Britten’s last major composition, Death in Venice, was given in 1973. As with so much of his work, his partner Peter Pears was the inspiration behind it, as much a confessional piece as an autobiographical one. Whether or not you are a fan of Pears’s voice, no one can deny the enormous influence exerted by Pears on Britten during the course of their nearly four decades together. Few other composers’ partners, straight or gay, can claim to have dominated a composer’s creative life to the same extent.

During work on Death in Venice, it became clear to Britten that the heart condition from which he had suffered was likely to be fatal and in the last few years of his life he was reduced to doing very little. He had been made a Companion of Honour as early as 1952 and awarded the most coveted British award, the Order of Merit, in 1965; less than six months before his death he was elevated to the peerage, the first composer ever to be made a Lord.

Britten wrote in a stunning variety of styles without ever losing the unmistakable ‘Britten sound’. More memorable than the melodies he wrote are the haunting moods and atmospheres he conjures up. The brooding, bleak flatness of the East Anglian landscape forever hovers round him. His friendship with some of the greatest artists of the day (including, most notably, horn player Dennis Brain, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and pianist Sviatoslav Richter) encouraged music which delights in virtuosity. The sea, too, played a major part in his creative process. ‘My parents’ house directly faced the sea,’ he wrote, ‘and my childhood was coloured by the fierce storms that sometimes drove ships into our coast and ate away whole stretches of the neighbouring cliffs.’ Britten came of age in 1934, the year in which Elgar, Holst and Delius died. He rapidly dragged British music into another era – his own.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.