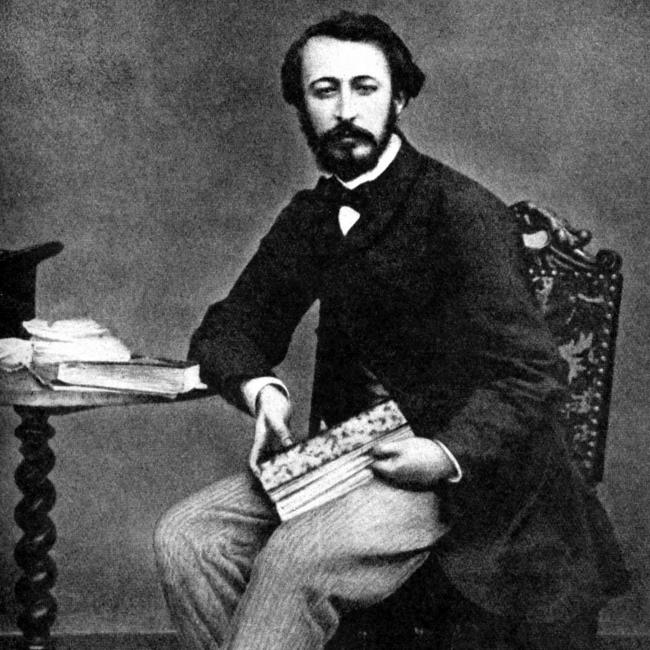

Saint-Saëns

Born: 1835

Died: 1921

Camille Saint-Saëns

Saint-Saëns was one of the most remarkable prodigies, indeed, he had an altogether remarkable mind: organist, pianist, conductor, caricaturist, dabbler in science, mathematics and astronomy, traveller, archaeologist, writer of plays, philosopher, essayist on botany and ancient music.

Explore Saint-Saëns's life and music...

Saint-Saëns's Piano Concerto No 2 – which recording is best?

This concerto may seem little more than a shallow showpiece, but there’s a lot at stake for the soloist, as Jeremy Nicholas discovers via myriad recordings... Read more

Top 10 Saint-Saëns recordings

There's much more to Saint-Saëns than the Carnival of the Animals, as these outstanding recordings amply demonstrate... Read more

Saint-Saëns was one of the most remarkable prodigies in the history of music – indeed, he had an altogether remarkable mind: organist, pianist, conductor, caricaturist, dabbler in science, mathematics and astronomy, critic, traveller, archaeologist, writer of plays, poetry, philosophy, essayist on botany and ancient music, editor of music and the composer of more than 300 works touching every area of music.

Saint-Saëns began playing the piano at two and a half (taught by his great-aunt), gave a performance in a Paris salon at five, began to compose at six and made his official debut aged 10. As an encore he offered to play any one of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas from memory. After the Paris Conservatoire, he competed unsuccessfully for the Prix de Rome – and again in 1864 when he was an established composer. His First Symphony appeared in 1853: Gounod was present and sent an admiring note of encouragement. As a pianist and organist of exceptional ability, he was much in demand and, at the age of 22, he secured the most prestigious organ post in France at the Madeleine. Here he developed his legendary gifts for improvisation – Liszt called him the greatest organist in the world – and soon famous musicians visiting Paris would make a point of stopping off at the Madeleine to hear him play – Clara Schumann, Anton Rubinstein and Sarasate among them. Hans von Bülow rated Saint-Saëns as a score reader and all-round musician greater than Liszt.

Saint-Saëns toured extensively as a pianist, both in solo concerts and in performances of his own piano concertos – his technique was apparently effortless. He became a professor of piano at the Ecole Niedermeyer in 1861 and 10 years later helped found the Société Nationale, dedicated to the performance of music by French composers. He composed at tremendous speed: his Op 12, the Oratorio de Noël, was completed in 12 days; a commission he had forgotten about produced 21 pages of full score in two hours; the popular Second Piano Concerto took three weeks from start to finish.

By the late 1860s Saint-Saëns was numbered among the top few great living composers, awarded the Légion d’Honneur at only 33, befriended by the leading musicians of the day and a habitué of the salon of Princesse Mathilde. His private life was not so fortunate. He was 40 when he married the 19-year-old Marie Truffot, sister of one of his pupils. The couple had two children but Saint-Saëns had little time for family life and in the first three years of his marriage he completed his opera Samson et Dalila, his Piano Concerto No 4, the oratorio Le déluge, a suite for orchestra and a symphonic poem, made a visit to Russia (where he became close friends with Tchaikovsky), composed numerous other short works, gave concerts and, in the spring of 1878, returned from Switzerland after writing a Requiem Mass.

His arrival coincided with a terrible tragedy: his two and a half-year-old son André had fallen out of a fourth-floor window; barely six weeks later his second son died suddenly of an infant malady. Three years after that, Saint-Saëns and his wife were on holiday and the composer one day, without warning, disappeared. Marie Saint-Saëns never saw her husband again (the couple never divorced) and she died aged nearly 95 in January 1950.

After 1890, he wrote very little of consequence and began to indulge in his passion for foreign travel – frequent visits to the Canary Islands and Algeria, and as far afield as Colombo and Saigon where, it’s said, he developed a close interest in the natives. As his music became less and less appreciated by the coming generation, he became proportionately more irritable, more outspoken in his condemnation of new music. He was still giving recitals three months before his death (he went on a concert tour of Algiers and Greece at the age of 85). When he announced his retirement in August 1921, he had been before the public for 75 years.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.