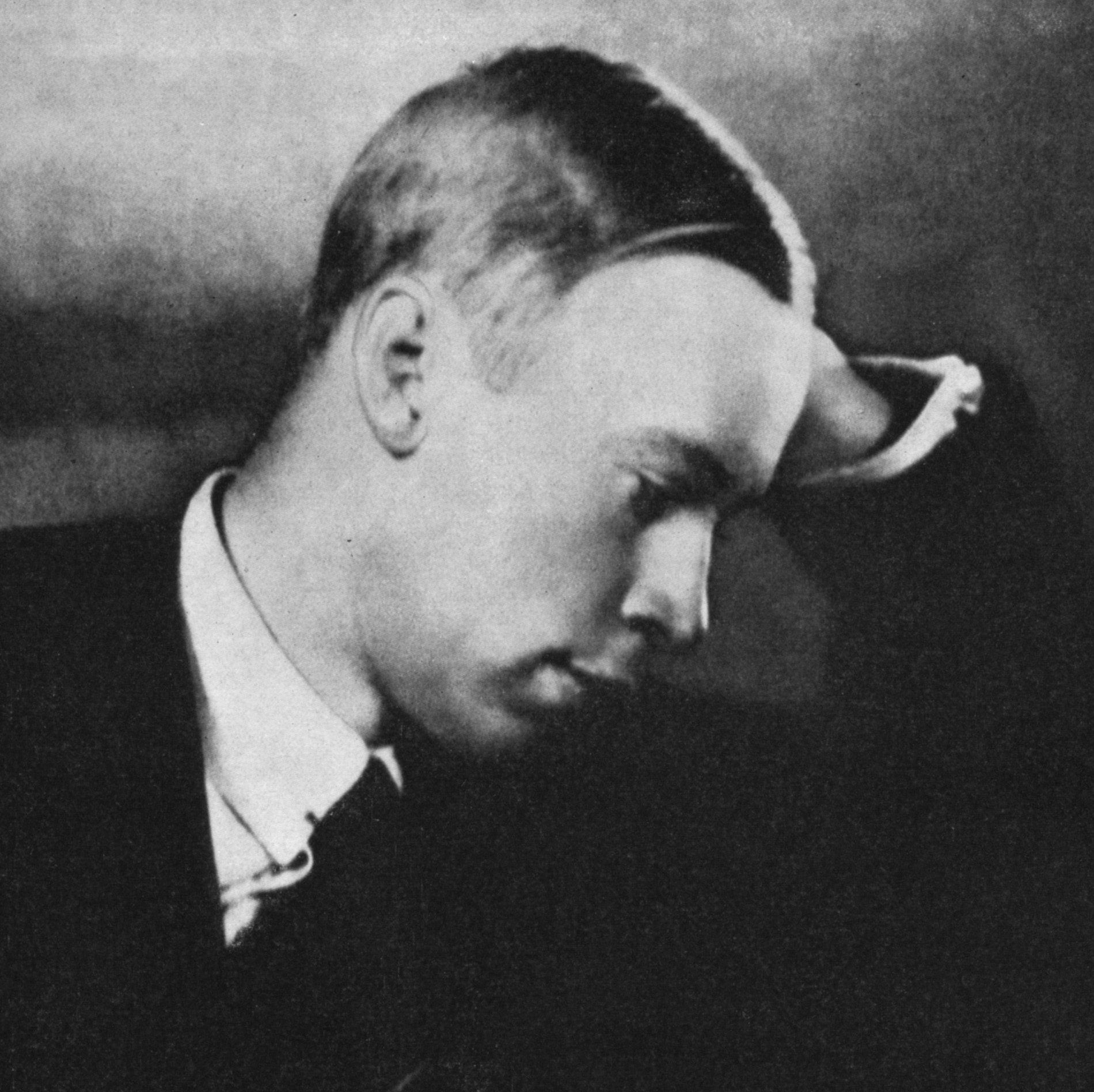

Prokofiev

Born: 1891

Died: 1953

Sergey Prokofiev

Sergey Prokofiev's (born April 23, 1891; died March 5, 1953) style seemed to be pre-formed, completely original and one which remained constant for his entire creative life.

Quick links

Sergey Prokofiev: a biography

Sergey Prokofiev died on the same day as Stalin. Apart from the final years of his life, he managed more successfully than any other great Russian composer living under the dictatorship to maintain his musical ideals.

He was a brilliant student. By the age of 13, when he entered the St Petersburg Conservatoire, he was already a good pianist and had produced an opera (aged nine), an overture and other works. He had the best teachers, including Glière, Liadov and Rimsky-Korsakov, and Anna Essipova – who had been married to one of the greatest piano teachers of the 19th century, Theodor Leschetizky – taught Prokofiev piano. Such a precocious, blazing talent inevitably rebelled against the stifling conservatism that confronted him.

Like Shostakovich and Britten, his style seemed to be pre-formed, completely original and one which remained constant for his entire creative life. Even before graduation, he caused a stir in musical circles with some of his compositions – the First Piano Concerto caused a furore with its violent keyboard gymnastics, unexpected harmonic and melodic twists and angular rhythms. Before he was 20, he was famous. But Prokofiev was no wunderkind who burns out after initial brilliance.

In 1918 he left Russia and travelled through Siberia to Japan and America, giving concerts of his own music, and in 1920 arrived in Paris. Here, he met another expatriate, Sergei Diaghilev, who commissioned three ballets, Chout, Le pas d’acier and L’enfant prodigue. Further commissions came from his publisher Koussevitzky and in 1921 he visited America again for the premiere of his opera The Love for Three Oranges.

After returning to Russia in 1927, where he was greeted as a celebrity, he flitted between his mother country, Paris and other European cities before deciding in 1932 to settle in Russia for good. Quite why he did this is open to question. Surely he knew to what political pressures artists were subjected. Stravinsky stated that it was because Prokofiev was politically naive, also because he had not met with all that much success in America: Prokofiev’s return to Russia, he said, was ‘a sacrifice to the bitch goddess’.

Why did he not live and work abroad in peace like Stravinsky and Rachmaninov? Perhaps he thought he was famous enough to be treated differently by the authorities. In this he was sadly mistaken and, after an initial period of co-habitation, the authorities and Prokofiev were at loggerheads. Nevertheless, some of his finest music was written in the 1930s and during the war years, despite increasing ill-health and the break up in 1941 of his marriage after an affair with a 25-year-old student, Mira Mendelson.

When the Central Committee of the Communist Party denounced Prokofiev, Shostakovich and others for ‘formalism’ – music that had no immediate function and did not extol the virtues of the wonderful Stalinist regime – a humiliating public apology appeared: ‘We are tremendously grateful to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party and personally to you, dear Comrade Stalin, for the severe but profoundly just criticism of the present state of Soviet music...We shall bend every effort to apply our knowledge and our artistic mastery to produce vivid realistic music reflecting the life and struggles of the Soviet people.’

Thereafter, in the few years left to him, Prokofiev churned out inconsequential scores, the equivalent of the paintings of tractors and chemical works that Soviet artists were producing.

The Gramophone Podcast: Prokofiev episodes

Freddy Kempf on Prokofiev

Exploring Prokofiev: Lisa Batiashvili

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.