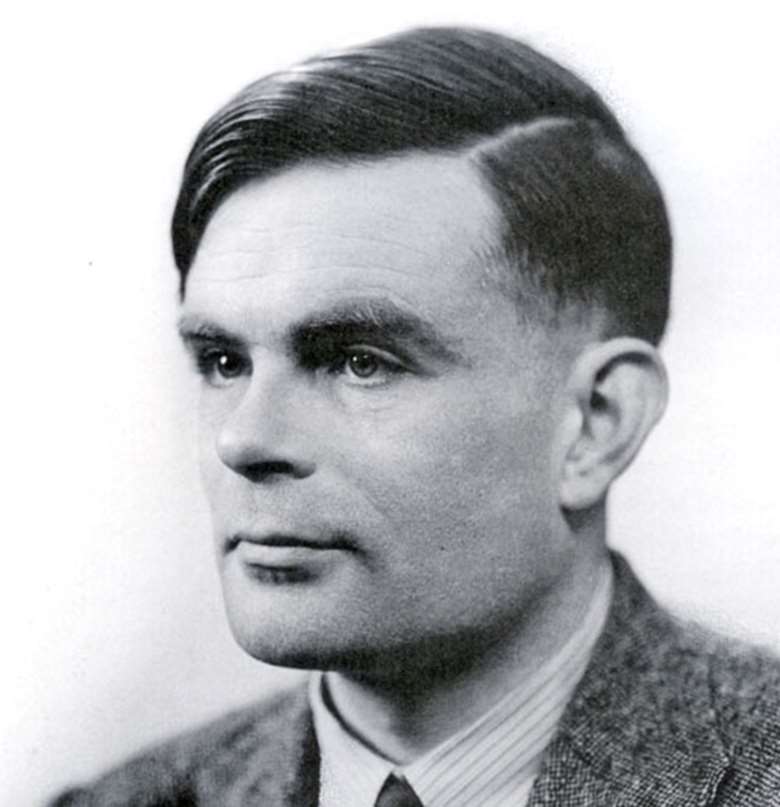

How do you explore the life, love and legacy of Alan Turing in music?

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Composers Nico Muhly and James McCarthy talk about their separate projects that aim to explore the codebreaker's extraordinary life.

James McCarthy and Nico Muhly have both recently been commissioned to write substantial new works about Alan Turing. James McCarthy’s 'Codebreaker' will premiere at the Barbican on April 26, 2014, Nico Muhly’s 'Sentences' will also premiere at the Barbican, but on June 6, 2015, starring Iestyn Davies. The two composers met up with Gramophone’s editor Martin Cullingford to discuss their different approaches to bringing Alan Turing to musical life…

James McCarthy So have you finished your piece?

Nico Muhly No, I haven’t even started it! I have sketches…

JM How long do you think it will take to write?

NM I’ve found that once I have a text that I like the actual composition is really fast. But it’s worth it to fuss over the text properly until it is correct. Basically, I can look at a page of text from a distance and know that I can set it, you can just see whether a text has a built in ‘sensibility’ to it.

JM Do you find it hard to explain to the writer why you need a text to be a certain way?

NM Sometimes what I’ll do is set an awkward phrase to music and then play it for the writer so they can see for themselves. But how did you do your text, what was your process?

JM I just thought about three key moments of Turing’s life: first, falling in love with Christopher Morcom, second was the war, and then finally his demise. Then I tried to find poetry to slot into those holes. And also I’ve got a separate character of Sara Turing (Alan’s mother) to help the audience understand what’s going on in the narrative.

NM A kind of Jiminy Cricket figure…

JM Yes, exactly!

NM And how long is the piece?

JM 55 minutes

NM That’s really long!

JM Yes – I hope it doesn’t feel that long at the premiere… And your piece is going to be around half-an-hour isn’t it?

NM It’s going to be 26 minutes. Once you get over 30 minutes then there are too many ideas!

Martin Cullingford Nico, tell me more about your piece – what aspects of Turing’s life are you going to explore?

NM I’m actually more interested in the science aspect, it’s much more abstracted. But we do spend some time in Cambridge and we also have the actual trial. The sentence of chemical castration is really crazily worded. But I have the advantage of just one singer, which is a faster moving fish than many combined voices…

JM In my piece the choir are all portraying Turing. I had this idea of getting them all to Method act, change their clothes and their hair and sing differently, like a proper Daniel Day-Lewis thing, and see if you can get 150 people to represent one mind. Because Turing’s mind was so polyphonic and interesting I felt that you could appropriately use 150 singers to represent that.

MC So are you trying the capture the mechanical nature of the enigma machine in your piece?

JM Well, yes, but more important is the Bombe machine that Turing perfected in order to decrypt the codes. I went to Bletchley to listen to the Bombe there. Nico, is your soloist playing Turing?

NM No. I asked the writer to avoid the first person pronoun. First of all because it’s impossible to set, don’t you think? ‘I’ – It’s so cumbersome. So, it’s more abstract. He’s a sort of observer, an observer with privileges.

JM Is it chronological?

NM Yes, I think chronological is the right thing. It ends with him dying. Actually, it will probably start with the Pardon, then go back, then end with him dying.

JM Oh, you have the Pardon, of course. I’d finished mine before the Pardon…

NM The Pardon was so offensive, I thought. It was bizarre.

MC James, did you feel like you wanted to change the piece in light of the Pardon?

JM No. I think it would have muddied the waters. I have got Gordon Brown’s apology on behalf of the British Government, which he made in 2009, which seemed a more genuine expression of regret. I could have written half an hour just about the Pardon alone.

MC Nico, at what point did you start exploring Turing’s life?

NM Well a couple of years ago there had been a resurgence of interest in Turing. And at the time I was reading about the Navajo language and how it had been used by the American Army as an internal code. That’s the kind of thing that I would spend weeks just obsessively researching for no reason at all. I tend to research things with no real goal in mind, I’m not thinking ‘I could really write an opera about this’. I just want to know more. I’m obsessed with everything. And then I read that book by Singh...

JM The Code Book.

NM …and it was so great. I started finding myself in the under-depths of the internet exploring codes and people who were interested in codes. And I thought, it’s such a musical thing, really. I had a vision of just doing something about codes and then I thought about Turing, but there’s actually not a lot of information to go on. Despite the fact that there’s so much information, there’s no information.

JM That’s true. We don’t really know what he really thought about much at all.

NM Right. And as with a lot of people who worked through the war there’s a real moral ambiguity. In America of course our big anxiety is about the atomic bomb. Thousands and thousands of people worked on this thing and, with the exception of Oppenheimer, there’s an intense dryness about the whole subject, you know, no one talks about it. And no one talks about it heatedly. You kind of think, did it actually happen? And similarly with this, you know that in breaking a code you’re saving lives but also, saving lives in war time means killing people. So it’s a complicated thing.

JM For me the image that resonated in my mind was of Turing working with this constant noise, rhythms of machines going on in the background and at the same time this puzzle that he was doing was going to affect the outcome of thousands of lives every day. And how that must have felt.

MC Nico, it’s interesting that with Iestyn Davies you’re using a counter-tenor voice because it is the most ethereal and pure kind of voice…

NM Right. It’s also the voice most linked to castration – chemical or otherwise.

MC In Two Boys you tried to capture the sound, as it were, of the internet, that vast mass of code that’s so complex and yet meaningful. Did that almost lead you into what you’re planning with this piece?

NM Yes, I think so. I mean, I think everything I write is about that. About code.

MC Where code, maths, science and humanity meet in a powerful way?

NM Exactly.

JM It’s the organic and the mechanical coming together, I think that interests both of us. I’m certainly interested in creating mechanical musical processes and then destroying them. There’s a moment when the war breaks out half-way through Codebreaker where you get 1940s dance music mixed with the fear of war and the sounds of the machines in a kind of cocktail.

MC Is that recreation of period quite an important part of the piece?

JM It is, yes. And the music for Sara Turing is bedded in a kind of Victorian parlour chamber music, just little whispers of it.

MC Historically, opera and oratorio has taken fictional stories or Biblical stories and often they are coded ways of being polemical, whilst being separate from reality. Recently in the last few decades we’ve seen an increase in the number of works that are very polemical, John Adams’s operas for example. Do you think this says important things about the relevance today of classical music?

NM What you are doing is asking composers to talk about the relevance of music, which is incorrect, because we’re writing it so we don’t know. We’re inside it. It’s your job to observe trends, not ours.

MC Yes, except that if you’re consciously choosing the subject matter, you’re bringing to audiences…

NM Well surely we’re not all being taught ancient Greek myths as we once would have been.

JM I do think that by setting an ancient Greek myth you’re immediately distancing yourself from our world today.

NM Yes. That’s the choice.

MC So for you it’s just natural. You’re just someone in this era writing about this era, whereas other people are consciously making the choice to distance themselves from that.

NM Yes.

MC So this just feels like the most natural thing to do as a composer.

NM Right. But on ‘Team Journalism’, it’s always like ‘why are you participating in this trend of writing operas that could be from CCN?’ And it’s so incorrect, but we have to answer and be polite, but I’m done with it. Choosing topical things is the norm. We don’t live in an allegorical situation. Once, the idea was that boys were taught Latin and Greek and made to tease out life-lessons from the ancients. But that’s not the method of educating children any more and instead you are taught to be a reader of things, read the world around you and produce art based on that reading. That is the default. So going back to Greece, going back to mythology is an affectation. Setting Nixon is correct.

JM What you’re effectively saying when you choose to set ancient myths is ‘my music has this timeless, mythic quality that speaks for eternity’. Whereas we’re just dealing with subjects that are important to us now, and 50 years from the now the music that was written now will all take care of itself.

NM James, does the orchestra function as a mechanical presence? I can see in your score that the chorus and orchestra do a bit of both. Sometimes the chorus has repeated text and the orchestra is more lyrical, so how do you get to the heart of the matter?

JM First of all, I don’t see a distinction between the chorus and orchestra. They are completely interchangeable in terms of the material. I think it all comes from the love, actually, I just set a love poem and all the music comes from that. There was so little that Turing wrote passionately about, but he wrote about that love for Christopher Morcom. I think it drove him onwards for the rest of his life.

NM And it’s easy to imagine that at the end, when all the maths have cancelled each other out in that algebraic way, when the code is solved, what’s at the end of it is Christopher, or the idea of Christopher.

JM I tried to read some of Turing’s mathematical papers, but I just couldn’t find much music in them.

NM I found music in the actual maths itself. The sense of constant data going around. For me the love mechanism animates the mechanical music. Maybe that’s the same as what you said. It’s either exactly the same or precisely the opposite!

MC Nico, how did your relationship with the librettist come about?

NM Adam Gopnick is a writer I’ve followed for years. He writes a lot about food. What I like about him is that he is an obsessive. He’s written a wonderful book about French table manners. Really it’s just an excuse for us to eat together!

MC And with a librettist you don’t have complete control over the words, whereas, James, you do.

JM Yes, I like that. I’m a bit obsessive in terms of control over a piece whilst I’m working on it. Once it is finished then it is over to the performers to play as they wish. I don’t sweat about the performance, just what goes on the page.

NM But you’ve done the ‘War Requiem thing’ of setting poems, which is hard, I have to say, because for me, the better the poetry the harder it is to set.

JM I’ve set a lot of music to words by a poet called Sara Teasdale in this piece. It’s great poetry for me as a composer, but as poetry per se...

NM But that is exactly what you want, you want bad poetry! That’s why Christina Rosetti sets so great. If you ever look at the words to Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony they are so bad, but the music is so good.

JM When you first start to compose you think you should be doing Tennyson…

NM But you really shouldn’t do it!

James McCarthy's 'Codebreaker' will premiere at the Barbican in London on April 26 (click for ticket info). Nico Muhly's 'Sentences' will premiere in June 2015 (click for ticket info).

For more information about 'Codebreaker' watch the short film below: