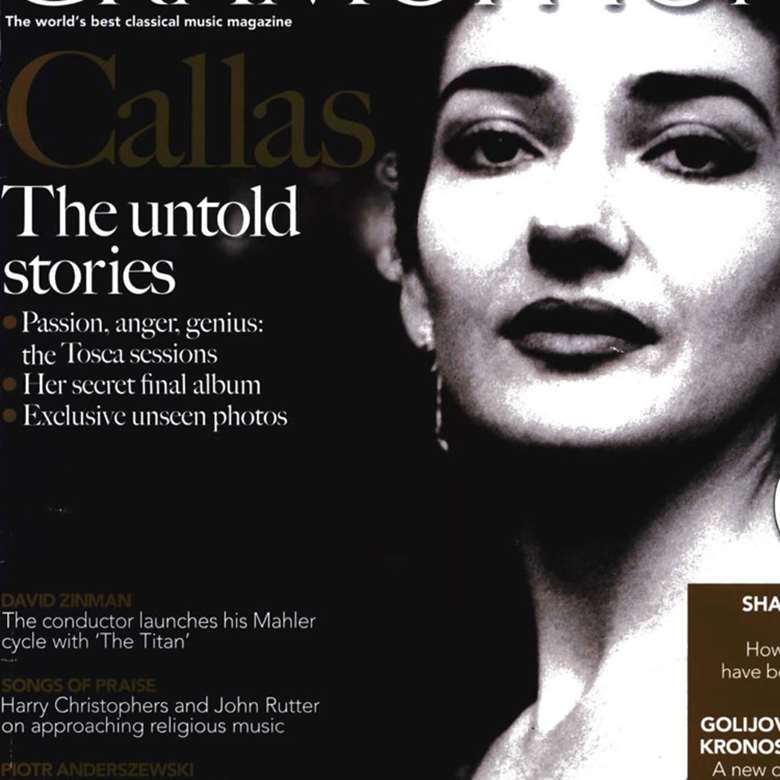

Maria Callas – the Tosca sessions

Gramophone

Thursday, March 12, 2015

Maria Callas’s famous 1953 Tosca, as Christopher Cook reveals for the first time, was riven by tension and driven by a relentless quest for perfection

This Tosca was always different; headstrong and full-blooded both when the red recording light was on and when it was off. Truly dramma per musica. Her co-star, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, called it ‘one of the finest recordings [I] had participated in and one of [my] best experiences of this kind’. Sixteen years after the sessions in August 1953, the Svengali-like Walter Legge listened again to the Tosca he had produced for EMI. They had ‘made immortal contributions through records to the artistic history of our time,’ he wrote to his heroine, Maria Callas, who was by now living in semi-retirement in Paris. The two had become estranged, and it was, wrote Legge, when he re-listened to their Tosca that he realised how trivial their disagreements were in the face of what they had together achieved (the letter worked: the producer and his Tosca were reconciled).

Art had begun as commerce, as is usual with the record business. In the early 1950s, Legge and EMI faced a problem. They were about to launch their own label in the United States, HMV Angel, rather than rely on American companies such as CBS for distribution. To run the new operation they had cunningly poached the formidable husband-and-wife team of Dario and Dorle Soria from Cetra records. EMI knew that Italian opera was a big seller across the Atlantic and the Sorias, according to EMI music consultant Tony Locantro, ‘were skilled at marketing and promotion and knew the American market very well. Certainly Callas to them looked like an extremely promising and exciting artist who would add lustre to the new Angel catalogue’.

As Legge wrote later: ‘I was rather late on the Callas bus. Italy was not officially my territory.’ He felt more at home north of the Alps, with Mozart and Herbert von Karajan in particular, but business was business and was, as ever, driven by talent – and the talent who had everyone talking was Callas. ‘At long last, a really exciting Italian soprano!’ wrote Legge. ‘My appetite was further whetted when one of her famous male colleagues described her as ‘not your type of singer’.’

A performance of Norma in Rome in 1951 convinced the deeply competitive Legge that he had to have her for EMI, though it would be a year and many meetings before he got her signature on a contract. It hadn’t been easy, he recalled. ‘She expected tribute at every meeting, and my arms still ache at the recollection of the pots of flowering shrubs and trees that Dario [Soria] lugged to the Verona apartment.’

Almost at once they began recording. First Lucia di Lammermoor in Florence, with Tullio Serafin conducting and Tito Gobbi and Giuseppe di Stefano in the cast. ‘I had found a fellow-perfectionist as avid to prove and improve herself as any great artist I have ever worked with,’ wrote a delighted Legge. Callas, and all of them, would need to be single-minded in their pursuit of perfection when they moved north to Milan to record what was clearly the headline project, Tosca onstage at La Scala. As well as solving the practical problems of finding a chorus and an orchestra, the La Scala connection was another marketing inspiration. Nothing ‘said’ Italian opera more clearly in North America than La Scala. By the first week of August 1953 Legge and his engineers were installed in the theatre. A recent revival of Tosca meant orchestra and chorus were already well inside the work. It had been conducted by Victor de Sabata, the formidable de facto music director of La Scala. His daughter Eleana calls him ‘the brain and the heart of that theatre’. The first session was planned for August 10.

Outside the theatre, and so inside too, the thermometer climbed relentlessly. It was the hottest summer Milan had known for over a decade. ‘I remember my father always conducting in a suit as if he was going to an office and certainly not to sweat on the podium. He never changed the way he dressed even when he was rehearsing,’ Eleana recalls, ‘but that recording was different. It was so hot, I have a picture in my mind of my father wearing a shirt with short sleeves, which is unbelievable for him!’

The heat was by no means the only pressure with which Callas and her colleagues had to contend. Legge was in his most determined mood, going to incredible lengths to get every detail perfect. According to Locantro, they spent hours recording each shout of ‘Mario’, as Tosca approaches the church of S Andrea della Valle, separately, with the singer in a different position. ‘Legge wanted to get the effect of her coming towards the church from the distance. He had in his mind something like reproducing an [actual] performance…So that the listener sitting in front of his gramophone would feel that they were sitting in the stalls in La Scala.’

Legge was not the only perfectionist in the theatre: the uncompromising de Sabata was his equal. Gobbi’s daughter Cecilia, watching the sessions, was ‘absolutely fascinated by de Sabata’s perfectionism. He wanted the orchestra on the stage and he took tremendous care in placing the instruments in different positions so that they would have distances between each other. I remember my father telling us that de Sabata wanted microphones spread in a certain way and he tested certain parts over and over again, checking the effect of putting the instruments and the microphones on different parts of the stage…There was no stereo then and what he was looking for was stereo avant le lettre.’

Once he was happy with the microphone and instrument placings, de Sabata turned to the performers. For half a century admirers have commented on the power the recording achieves at the end of Act 1, with the chorus singing a Te Deum as Gobbi’s godless Scarpia fantasises about Tosca. It was, recalls Cecilia Gobbi, a gruelling process. ‘The Te Deum was repeated 48 times. The orchestra was perfectly all right – it was after all the orchestra of La Scala. And my father didn’t make any mistakes – he knew the part so well. But de Sabata was never happy because he couldn’t find the right balance between all the elements.’

It was, for everyone, utterly exasperating. The implacable de Sabata drove them back over the music again and again. Years later Gobbi told producer and Gramophone critic Mike Ashman how the cast were pushed to their limits: ‘We kept on retaking the end of Act 1 from the last bit of the scene with Tosca. What really infuriated us was that everyone knew that Take Nine was ‘it’ – the hot one.’ And indeed, that was the take which was finally used.

Just how many takes there were depends on who you talk to. Ashman says it was 16 or 17, Cecilia Gobbi 48, Legge plumps for 30 and Eleana de Sabata goes for 37. After one take, Eleana remembers ‘my father furiously throwing away the phone [which connected the conducter with Legge and his engineers]…From upstairs they told him, ‘Maestro, it was fantastic but there is a strange sound’. It turned out to be a coal merchant delivering fuel for the theatre’s ancient heating system which had ‘created some kind of dark vibration’.’

Eventually, Callas had had enough. Gobbi told Ashman: ‘De Sabata called for yet another take, and Callas stopped, pointedly took off her glasses and said, looking straight at de Sabata, ‘‘Maestro, I cannot see you any more’’.’ Without her glasses Callas was notoriously short-sighted. A gasp went around. It was the closest Callas came to going on strike. A battle of wills had been joined with one of the most fearsome conductors, and it was de Sabata who backed down.

But not for long. The bells of Rome at the beginning of Act 3 found the conductor and his producer pursuing perfect balance once again. Eleana remembers her father ‘was moving the bells into different areas to receive an echo that would be like a stereophonic effect. And eventually he did obtain a special effect of a space between the sounds by…moving the bells a little bit away from the microphones’. They eventually put them in the second gallery.

Legge and de Sabata were working technical and musical wonders. Among his players, the conductor attracted admiration tinged with fear. ‘He was a severe musician like many others, but he was a good character,’ says Franco Fantini, a pit violinist. ‘He had a musical intelligence, a clarity of beat.’ Armando Burratin, a viola player who was there throughout the sessions, said ‘when De Sabata did ‘‘Vissi d’arte’’ he always asked for more. He was never satisfied. He was great, but he went a bit too far. He was strange – always the artist. And we know what artists are like!’

Callas’s musicianship would have come as no surprise to de Sabata but, when it came to Tosca’s great aria, even he must have been thrilled by her total concentration, the way in which she seemed to live every bar of ‘Vissi d’arte’. None the less, Walter Legge wrote about her being ‘put through de Sabata’s grinding mill for half an hour until he was satisfied with her line at the end of Act 2, ‘‘E avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma’’.’ It’s hard to believe that tempers didn’t continue to fray and temperament flare up that hot August. Callas was notoriously volatile, Legge writing that she ‘was not a particularly lovable character except to her servants and her dressmaker.’ But she had the La Scala musicians rapt. ‘Callas, apart from being a great singer, was a great actress, a personality,’ recalls Fantini, ‘She was a woman of the stage, she was never just a singer. When she performed you saw the character transformed in the setting. She played Tosca and she was a grand woman of the Roman aristocracy.’

Listen to the recording and it’s clear that Callas and Gobbi are developing a very special partnership, particularly in Act 2, he the oily-tongued oppressor with that menacing hooded quality to his voice and she the desperate victim allowed one brief moment of emotional repose in her great secular prayer ‘Vissi d’arte’. That relationship is perhaps not so surprising. Cecilia Gobbi says the kinship between them ‘was there from the very beginning because they were both theatre animals’. To which Tony Locantro adds: ‘Remember that [Gobbi] learnt his trade in Rome under the conductor Tullio Serafin, who encouraged him to look into the dramatic side of things and to dig deeply into a role to find the character and the right tone of voice. The same things that Callas was so good at.’ For if de Sabata brought his own special brand of genius to the Tosca recording, the influence of Serafin still pervades Callas and Gobbi’s performance. Both credited him with teaching them the fundamentals of musical drama. ‘[Serafin] taught me that there must be an expression; that there must be a justification,’ Callas told one interviewer. ‘He taught me the depth of music, the justification of music. That’s where I really drank all I could from this man.’

One could argue that the emotional power they generated on this recording changed the way we hear Puccini’s opera. If Tosca had once belonged to the artists – Tosca the singer and Cavaradossi the painter – now it’s the torturer and his victim we hear. ‘When you have one singing actor on one side and another singing actor on the other the result is not one-plus-one-makes-two. It makes more because they interact and something grows,’ says Cecilia Gobbi. ‘The very special thing which Maria and my father had, is that they could convey this through a record. You could listen and see them.’

The last session at La Scala was on August 21. They had been recording with just two free days since the 10th. All were utterly exhausted. Costs, as Walter Legge later grumbled to Lord Harewood, had spiralled as – thanks to the relentless perfectionism – the number of sessions needed had doubled. Wearily, Legge looked at the reels and reels of tape that he and his team would turn into the final product and invited de Sabata to help them select the best takes. ‘My work is finished’, said the maestro. ‘We are both artists. I give you this casket of uncut jewels and leave it entirely to you to make a crown worthy of Puccini and my work.’

For Callas, for Gobbi, for de Sabata himself, this Tosca had been perhaps the most intensive recording project they would ever undertake. And yet, despite the heat, despite the extended recording schedule and the temperament, for once everything locked into place. Callas and her co-stars had set new performance standards for Puccini’s opera, which many feel have yet to be surpassed on record. And for the soprano’s many fans, just about everything you need to know about her talent, her unique dramatic gifts and the interpretative power of a truly magnificent singing actress is here on this recording.

This article originally appeared in the June 2007 issue of Gramophone.