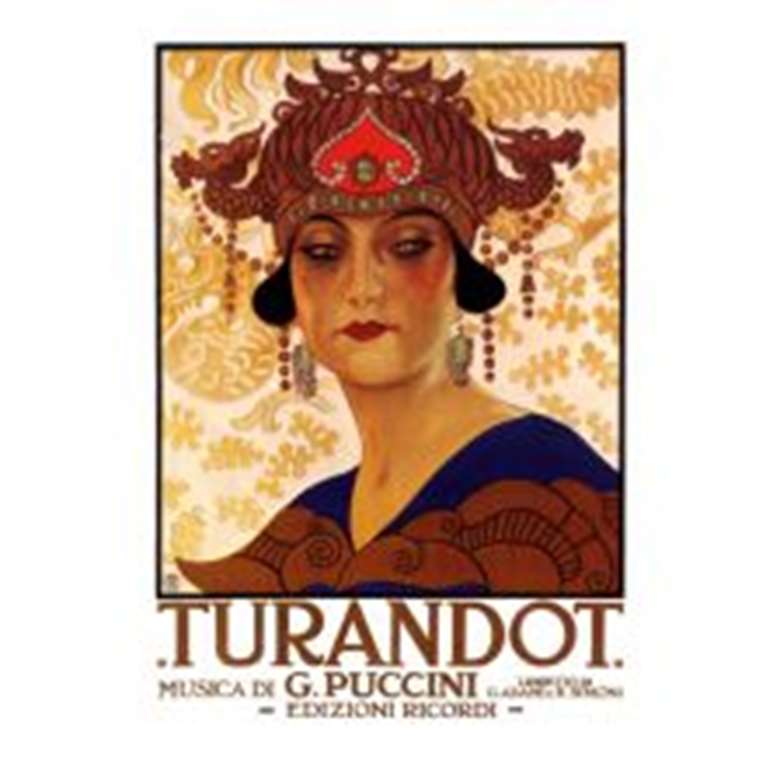

Puccini's Turandot: a survey of recordings

Gramophone

Thursday, April 24, 2014

On the anniversary of the premiere on April 25, 1926, John Steane looks at the recordings of Puccini's last opera

(First published as the 'Gramophone Collection' in July 2008.)

In the Land of Might-Have-Been is a department of Recordings That Never Were. The ledger for the year 1926 has an entry for April 25 reading 'Milano: Teatro alla Scala: Puccini: Turandot: Prima'. A brief note explains that the premiere of this, Puccini’s last opera, ended with the conclusion of section figure 34 in the Third Act and that at this point the conductor, Maestro Arturo Toscanini, turned to the audience and spoke the following words: 'A questo punto termina l’opera per la morte del compositore'. Using the hypothetical mood favoured by the scribes of Might-Have-Been, the entry notes that 'Otherwise the opera were recorded complete'.If only! And yet it could so nearly have happened. Just one month later, on May 31, engineers of His Master’s Voice moved their equipment into London’s opera house at Covent Garden to record the famous bass Chaliapin live from the stage in a performance of Mefistofele. The experiment was successful, the quality fine, and arrangements were made to record Turandot in its second run at Milan under Ettore Panizza. All that emerged were a couple of choruses. Test pressings of unspecified passages were made – and accidentally destroyed.

This tale of woe must continue for one more paragraph. Excerpts from live performances at Covent Garden were indeed recorded in 1937. That year Eva Turner returned to the house in the role for which she had become famous the world over, and the veteran tenor Giovanni Martinelli reappeared after 18 years’ absence. The Liù of one performance was Mafalda Favero and of the other Licia Albanese. John Barbirolli conducted. Liù’s 'Signore, ascolta', Calaf’s 'Non piangere' and 'Nessun dorma', Turandot’s 'In questa reggia' and the Riddles scene are heard from two performances: that is, each is recorded twice. They were issued, remastered by Keith Hardwick, by EMI in 1988. Of them much could be said; unfortunately the disc is no longer available!

The first complete recording dates from 1938 and survives well. Initial reaction to the sound may well be one of startled gratitude. The good, authentic Italianate resonance of the Mandarin’s voice is caught with such immediacy that one might be treating oneself to a front seat in the stalls. When the other principals enter it is like having the aural equivalent of opera-glasses trained on them. Francesco Merli was one of Italy’s leading tenors (this is no reach-me-down cast), and his voice has something of the thrill of Corelli’s and the body of an Otello. The Liù is the subsequently still more famous Magda Olivero, her quick vibrato a feature common then but rarely heard nowadays, the character that of strength animating frailty. The Ping is Afro Poli, of all the Italian baritones of his generation perhaps the most likeable in all-round accomplishment. And then, at last, at the start of the second disc, we hear the voice of Turandot herself, the formidable Gina Cigna, phenomenal in the power, the fullness of tone and the breadth of her high notes. Orchestra and (particularly) chorus perform well under the Turin house conductor Franco Ghione, and, despite the shallowness of perspective which gives a rather unremitting effect to the sound especially in the big scene of Act 2, this is definitely not a recording to write off on account of its age.

Of the four early post-war sets three remain available (the casualty had Gertrude Grob-Prandl, whom many will remember in the role at Covent Garden, singing Turandot and was on the long-defunct Remington label). If one of them had to go it should probably be the Decca recording under Alberto Erede, yet this too would be a loss, principally in the distinguished performance of Inge Borkh in the title-role. Her Calaf, Mario del Monaco, is rigidly, implacably loud, and the Liù, rather too close to being a Turandot herself, Renata Tebaldi.

The princess of the era

The Turandot of her age was, of course, Birgit Nilsson. As Eva Turner had done before her, she embodied the role as it is usually understood, the steely determination represented by firm, penetrative tones, the obsessive programme of sexual retribution voiced in those high, cleaving notes as by some nightmarish bird of prey. Singers whose attributes fit this description tend to produce sounds that are harsh and maybe shrill; and if their voices do not show signs of wear (and many do) when they first undertake the role it will not be long before they do so if they continue in it. Turner and Nilsson were glorious exceptions: their voices were like musical glass, clear, shiny and unflawed. It was in this matter of quality that they surpassed successors such as Ghena Dimitrova and Eva Marton, and records make that clear enough. The earlier of Nilsson’s studio recordings might have slipped out of circulation by this time but for the casting of Jussi Björling as Calaf, one of his last complete opera recordings and in a role he never sang on stage. At times he is squadrato, a word Puccini used of a very different tenor, Alfred Piccaver, meaning 'square'. Confronted with the riddles and later alone with the 'principessa di morte' he presents a front of merely stolid determination, yet from time to time he flares up with exultancy and often the scrupulous legato and a touch of tender feeling combine movingly. Chorus work is fine but the Rome orchestra is not always at one with its conductor for the occasion, Erich Leinsdorf. And Nilsson’s Turandot can be enjoyed at least as well elsewhere.

Five years later her Calaf in the studio, as in so many stage performances, was Franco Corelli. This was a partnership that struck sparks: there was always a frisson, a sense of occasion and expectancy on Nilsson-Corelli nights. The same Rome Opera forces are in use, under Francesco Molinari-Pradelli whose feeling for Puccini is more idiomatic than Leinsdorf’s and his approach equally energetic. The new Liù is another Renata, this time Scotto, her voice at that time (1965) still an apt instrument, her responsiveness to words and music altogether more imaginative. As for Nilsson and Corelli, they sing the parts they were born to, magnificently both.

But here an excursion is in order. On March 4, 1961, the famous 'Saturday afternoon at the Met' broadcasts transmitted a performance so excting that news of it spread far and wide. I had a letter telling how it had thrillingly filled a flat in Montreal with its glory, especially that of its 'new tenor' ('There’s a voice-and-a-half'). The conductor, as I remember, was unnamed by my correspondent, but turned out to be a still more eminent newcomer to the house, one Leopold Stokowski. He made his way through the orchestra, so the radio announcer observed, 'slowly, very slowly' on crutches, having recently broken his hip. Of course, with Stokowski you were never quite sure, but as a man of almost 80 years he probably deserves the benefit of any doubt. His taste for exotic coloration found plenty of scope and he clearly relished the splendour, the barbarism and the breadth.

As we hear in what I suppose was a pirated recording (but now with a respectable place in the catalogue), the singers were in fine form. The young Anna Moffo sings an appealing Liù (the appeal directed perhaps a little too pointedly at the audience on the conclusion of her first aria). Nilsson’s voice sounds warmer and fuller, and Corelli is caught so faithfully that the thrill of recognition, usually confined to a singer’s first notes, is potent throughout. But what also makes this so exciting is that the recording has exceptional presence, so that one is in the thick of it. The later of the studio versions is more safe (and in the concluding duet more complete), but this from the Metropolitan is an experience, unique in kind among all these recordings.

Getting to the heart of the role

Nilsson was a natural for Turandot. It might be assumed – but wrongly—that Maria Callas was another, and – wrongly again – that Sutherland was not. The Callas recording (Serafin the reliable conductor) was made eight years after she had given up the role on stage. In its present reincarnation on CD its value lies largely in Callas’s psychological insights (her voice having an acidic quality on high notes) and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf’s pure tone and stylistic promotion of the slave-girl Liù to the aristocracy. The Calaf, Eugenio Fernandi, justifies his own promotion but his casting still has something of a faute de mieux about it.

The genius of Callas herself finds most eloquent expression in Turandot’s great solo on her entrance. She seeks out the humanity of this monstrous woman and finds the source of her vengeful mission in a deep tenderness. In doing so she points up the hardest riddle of all, for how, given the way she presents herself in the fable and, usually, in her singing, can anybody love her, as Calaf evidently does? And, strangely perhaps, it is not Callas’s own vocal performance that provides the answer, but Joan Sutherland’s. The idea of Sutherland as Turandot seems all wrong (and she never sang the role on stage), but she had the necessary power and the ease on high, and the recording shows that she could summon up the rest. And hers was a beautiful voice. The type of voice 'made', as we think, for Turandot is bright and steely, its high notes mercilessly penetrative, its strength that of the warrior-soprano. But that isn’t loveable. To be psychologically credible, the voice (which in recorded opera is the character) must have humanity latent in its power, and there must be some element of feminine beauty in its timbre.

Zubin Mehta, the conductor of Sutherland’s Turandot, is most clear of all in his appreciation of structure, and is as effective as any in his control of dynamics. The London Philharmonic Orchestra bring a freshening touch to the score and the John Alldis Choir are the most expressive of recorded Pekinese. Perhaps they are inspired by their Emperor, none other than Peter Pears, singing with an almost saintly distaste for the whole barbaric business. Luciano Pavarotti is an inspired Calaf, Caballé a Liù whose soft B flats are the perfect answer to Turandot’s fortissimo. With Tom Krause as Ping and Nicolai Ghiaurov as Timur, the cast list is spicy with promise, all of it richly fulfilled.

This is the last of the classic recordings. Montserrat Caballé went on to record the role of Turandot herself but it is no pleasure to hear that lovely voice brought under such pressure. The Strasbourg conductor Alain Lombard favours enervatingly slow speeds and the recorded sound is not always well balanced. José Carreras’s Calaf, young and ardent, is the best feature here, as it is again in a recording live from Vienna, though by this time, some six years later, the openness of his upper notes is beginning to spell danger. Eva Marton has succeeded as the reigning Turandot, well up to it in volume, range and stamina but impure in tone, frequently unsteady and nearly always unsubtle. Maazel treats the score, sometimes excitingly, as a sequence of effects.

Katia Ricciarelli, the very acceptable Liù of that recording, becomes the miscast Turandot of another from Vienna, this time a studio product conducted by Herbert von Karajan. His masterly handling of the score and Domingo’s royal Calaf almost suffice to add this to the classics; but it’s Turandot without the Princess. Ricciarelli is thoughtful and musical in her approach but is not equipped vocally. Eva Marton certainly had the equipment but by 1990, when she recorded the role again, the quality had deteriorated further. Again the Calaf and Liù do much to recommend the recording: Ben Heppner is incisive in tone (though he doesn’t make the words work for him) and Margaret Price brings the warmest voice to be heard in the part on records. Roberto Abbado conducts a faithful, well controlled performance.

From stage to screen

Another admired Turandot of the 1980s was Ghenna Dimitrova and one much in demand in recent years is Giovanna Casolla. Dimitrova, recorded in a live performance from Genoa under Daniel Oren, is not unlike her contemporary Marton in the balance of faults and virtues: I personally prefer her relatively compact tones, though the upper notes have the familiar surface-scratch. Few (I hope) would find Casolla’s uneven tones acceptable on record even if her high notes proved exciting in the flesh. The Calaf opposite Dimitrova is the very adequate Nicola Martinucci, Casolla in her version on Naxos has the undistinguished Lando Bartolini. The Genoa recording is strengthened by Cecilia Gasdia’s often exquisite Liù and Roberto Scandiuzzi’s sonorous Timur. Casolla and Bartolini sing in a performance the best feature of which is the work of the chorus; with the admirable Sergei Larin, Casolla’s other recording, under Mehta, was made live in the Forbidden City itself and is skilfully engineered to make the best of a well nigh impossible job.

The DVD of that production is a curiosity rather than an artistic experience. I’d no doubt have been impressed by the spectacle like everybody else if I’d been there, but on the small screen it is pure goggle-box. The principals, especially Larin, gain nothing by being seen, and the sound is certainly no better. Far preferable is a production filmed at the Verona Arena in 1983 with principals (Dimitrova, Martinucci, Gasdia) from the Genoa recording. Here the singers actually benefit from being seen and the setting is magical. Magic is, however, a notable absentee from the San Francisco production of 1994, celebrated for its sets by David Hockney, whose straight lines, primary colours and flat surfaces will swat dead any story-teller’s emergent fantasy quicker than he can say 'Once upon a time'. And how good it would be if one could then recommend the 1958 black-and-white for the handsome presence of Corelli. But no; his face is mostly expressionless and still more often not clearly visible at all.

All of these, video or sound recordings, play the final scenes, after Liù’s death, according to the printed score (many omitting Turandot’s solo 'Del primo pianto'). As we now know, this is a significantly shortened version of Alfano’s original reconstruction. The full version has now been performed and recorded, and though most critics were unconvinced my own reaction, for what it’s worth, was very positive. Since then, another version has been composed (and received with much more respect) by Luciano Berio. At least it makes us think again. Berio was impressed by evidence which suggested that the reason why Puccini failed to complete the opera was not so much his failing health as the problem of Turandot’s change of heart and the doubtful validity of the grand love duet he proposed as the main feature of the finale. Like Alfano, Berio uses Puccini’s sketches but exploits modern harmonic and orchestral resources to make us feel how problematic the relationship is. The opera now ends quietly and though the chorus has a part there is no one-more-time altogether-now reprise of 'Nessun dorma'. The writing is thoughtful and subtle, and the effort to absorb and integrate Puccini’s surviving ideas impresses as sincere. On its own, it stands well: the trouble is that it has to stand with the rest of the opera, the musical language and dramatic mode of which are of another kind.

The Top Choice: Sutherland; Pavarotti / Mehta (Decca 414 274-2DH2) Buy from Amazon

'Sutherland as Turandot' does not sound right – till heard. All the musical requirements are met and, dramatically, her change of heart becomes credible with the more feminine voice-character. Pavarotti, Caballé, Ghiaurov, Krause and Pears are strongly cast. Mehta’s conducting and Decca’s recording: both admirable.

The Live Choice: Nilsson; Corelli / Stokowski (Memories HR4535/6) Buy from Amazon

March 4, 1961: an exciting Saturday afternoon at the Met. Seventy-eight-year-old Stokowski conducting his first opera there, Nilsson and Corelli singing their great roles together, and the recording places the listener in the thick of it.

The Video Choice: Dimitrova; Martinucci / Arena (Castle CVI2004) Buy from Amazon

The Verona Arena makes a magical setting and the production is skilfully filmed. And the singers (Dimitrova, Martinucci and Gasdia in the lead) look at least as good as they sound.

The discography

Date / Artists (Turandot) (Calaf) / Record company (review date)

1938 Cigna (T) Merli (C) Turin RAI Orch / Ghione Arkadia 2CD78016; Naxos 8 110193/4; Warner Fonit 5046 71223-2; Nuova Era HMT90002/3 Buy from Amazon

1955 Borkh (T) Del Monaco (C) Santa Cecilia Academy Orch / Erede Decca 452 964-2DF2 (4/99) Buy from Amazon

1957 Callas (T) Fernandi (C) La Scala Orch / Serafin EMI 556307-2 (11/87); 509683-2 Buy from Amazon

1959 Nilsson (T) Björling (C) Rome Op Orch / Leinsdorf RCA 09026 62687-2 (9/87R); RCA 82876 82624-2 Buy from Amazon

1961 Nilsson (T) Corelli (C) Metropolitan Op / Stokowski Memories HR4535/6 Buy from Amazon

1965 Nilsson (T) Corelli (C) Rome Op Orch / Molinari-Pradelli EMI 769327-2 Buy from Amazon

1972 Sutherland (T) Pavarotti (C) LPO / Mehta Decca 414 274DH2 (5/85) Buy from Amazon

1977 Caballé (T) Carreras (C) Strasbourg PO / Lombard EMI 565293-2 (12/94); 509173-2 Buy from Amazon

1982 Ricciarelli (T) Domingo (C) VPO / Karajan DG 423 855-2GH2 (5/85) Buy from Amazon

1983 Dimitrova (T) Martinucci (C) Arena di Verona Orch / Arena Castle DVD CVI2004 Buy from Amazon

1983 Marton (T) Carreras (C) Vienna St Op / Maazel Sony Classical M2K39160 (10/85) Buy from Amazon

1989 Dimitrova (T) Martinucci (C) Genoa Teatro Comunale / Oren Nuova Era 678687 (11/89) Buy from Amazon

1990 Marton (T) Heppner (C) Munich Rad Orch / R Abbado RCA 09026 60898-2 (12/93) Buy from Amazon

1994 Marton (T) Sylvester (C) San Francisco Op / Runnicles ArtHaus DVD 100 088 Buy from Amazon

1998 Casolla (T) Larin (C) Maggio Musicale Fiorentina Orch / Mehta RCA 74321 60617-2 (1/99); 74321 60917-2 (1/00) Buy from Amazon

2001 Casolla (T) Bartolini (C) Malaga PO / Rahbari Naxos 8 660089/90 (7/03) Buy from Amazon