The return of the LP – what lies behind the renewed appeal of vinyl?

Andrew Mellor

Thursday, June 30, 2016

What’s the appeal of vinyl records, and will they eventually outsell the CD? Andrew Mellor investigates

Drive east into the wilderness from Santa Fe, and after about two hours you might spot an elliptical pattern of circles and diamonds etched into the New Mexico desert floor. It’s the logo of the Church of Spiritual Technology, a branch of the Scientology movement. Somewhere deep beneath that spot is a set of steel-lined tunnels housing thousands of titanium records, each preserving the voice of L Ron Hubbard, Scientology’s founder. The records can only be played, apparently, using a specially designed, solar-powered turntable. In the event of a global holocaust, new or surviving species are invited to consult the pictorial instructions, set the turntable in motion, and get a gratis crash-course in Scientology, courtesy of its legendary patriarch.

As underlined in Greg Milner’s penetrating history of recording, Perfecting Sound Forever, the Scientologists are on to something with their New Mexico record library, whether or not you subscribe to the beliefs their records espouse. Perhaps they know that with digital music we have, in one sense, been sold a myth: that digital files aren’t only (more often than not) subjected to the worst kinds of compression, but that they’re also, as this magazine’s Audio section has explored, impermanent – even more susceptible to decay and disappearance than magnetic tape. That’s before you’ve considered the availability of the specific technology needed to ‘access’ those files, whether they’re floating on a screen or embedded with the plastic of a compact disc. If you want to make a recording that you’ll be able to hear long after the earth’s scorching, cut it onto a record and bury it deep underground.

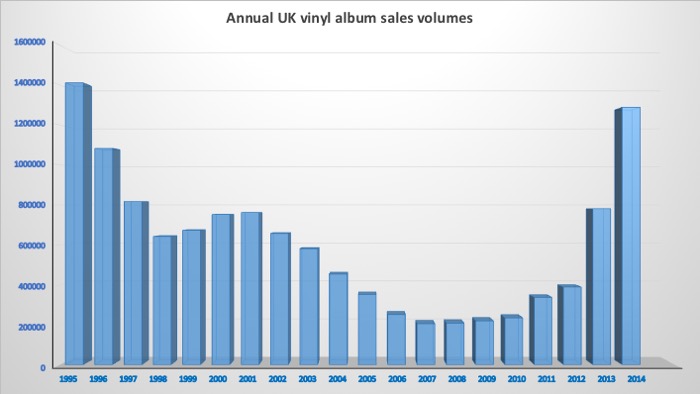

However much importance you might attach to the idea of physical permanence, it’s worth stopping for a moment to consider the tenacity of the humble old record and its technology rooted in Edison. Who would have thought, when the digital revolution took hold over a decade ago, that the music industry would soon be looking hopefully in the direction of the long-lost LP? For the past seven years, vinyl is the only physical format that has seen consistent growth in sales across all genres. That’s right, vinyl records: heavy, oversized, expensive to warehouse, extortionate to ship, but somehow unerringly appealing – objects of desire and promise that have stirred feelings of collective optimism in the belly of an industry eager to recapture the good old days.

When Milner’s book was published in 2009, this growth in vinyl sales was in its infancy. Milner was able to refer affectionately to today’s analogue music lovers as ‘a crowd forced on to a reservation, speaking a dying language…on the wrong side of history and proud of it.’ But before we rejoice in that crowd’s emancipation, it’s worth checking on the statistics. Of all the music sold in 2014, 1.5 per cent was on vinyl, which means the format still hasn’t recouped its market share of two decades before – which was 1.6 per cent (the figures for classical music in isolation aren’t available, though experts predict the percentage would be even smaller). What’s got record labels so excited isn’t necessarily that percentage figure, but the fact that it’s moving – and in an upward direction. Most labels haven’t seen growth like that for years.

All three classical ‘majors’, along with a small gaggle of independents, are steadily releasing vinyl right now. And that’s despite significantly higher manufacturing costs (against manufacturing costs of a little over zero for digital music). Sony Classical took the extraordinary step of launching its new cycle of Mozart’s Da Ponte operas on the format; quite a way to announce one’s return to a niche market. Last October, Warner Classics’ Erato imprint released Alexandre Tharaud’s recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations on LP. As of 2012, Linn Records has channelled between two and four of its yearly headline classical releases onto vinyl – recordings from John Butt, Robin Ticciati and Kuniko – as a counterpoint to digital releases, physical and virtual. The Universal labels started to offer samples of their reissue box-sets on vinyl a little over two years ago, and now release single-disc reissues and frontline new recordings on the format as well. Linn’s equipment arm, meanwhile, shipped 70 per cent more new turntables in 2015 than it did in 2012.

When Universal re-entered the market via a slimmed-down, six-LP edition of its 53-disc Decca Sound CD set in 2013, it was, in the words of the company’s Vice President for Classical Catalogue Barry Holden, ‘to dip our toes in the water’. If the water wasn’t exactly hot, it was at least lukewarm. ‘We made 2000 sets, which doesn’t sound like much – actually, it isn’t that much – but over the course of a year they seemed to all filter out through our retail channels. So we tried it again with our Mercury Living Presence box – Mercury being a cult label and originally a vinyl label. And that set did even better. When I say even better, I mean no more than 3000 sets for the whole world.’

For once, the headline numbers might not be the most important, which is why Holden qualifies his statement. Universal can make its vinyl reissues schedule work because a high manufacturing spend is offset by low design, editorial and royalty costs. For box-sets already issued on CD – or for classic albums, many from the so-called ‘TAS List’ (compiled by the US-based audiophile magazine The Absolute Sound) of the finest sound recordings, reissued with original artwork and liner notes – there’s no new editorial to pay for and minimal mechanical rights to negotiate with Universal’s individual copyright-owning labels. ‘That made it easier to justify,’ says Holden, ‘but there was no question that it was a bit of a risk.’

It still is. ‘If you can tell from the look on my face that we’re still tentative about it, then we are,’ says Holden. ‘Vinyl is a significant and useful niche but it’s still a niche. In terms of subsidiary costs like shipping and storage, it gets quite an easy ride through Universal’s systems. Having said that, I’m pleased to have it. If vinyl adds 1 or 2 per cent to our revenue without losing money and without the company rearing up in revolt, then we’ll do it. It’s not going to reshape our business but we’ll support it as long as it supports itself.’

The question, then, is who’s buying it? ‘We just don’t know,’ says Holden. ‘All we have is anecdotal evidence, things we gather from Amazon reviews and the like. Our gut tells us that it’s very market-specific; that there are significant pockets of interest in Asia, Japan, China, Hong Kong, the US and Germany; France and the UK to a lesser extent. Anecdotally, it seems to appeal to wealthy people aged 40 plus. Some of them are returning to vinyl and some are establishing a first relationship with it.’

Snapshot data from Linn Records echoes that perceived geographical trend. And like Universal, Linn has recognised that if the market is small, at least it’s reliable. Typically, a vinyl record on Linn will account for 5 per cent or less of an album’s total sales across all formats. ‘That may be small, but we do limited pressings and it’s a fairly set group that responds,’ says Linn’s Kim Campbell. ‘We’re talking about an older demographic, people who loved vinyl in its heyday and are rejoicing that it’s coming back.’ There’s little evidence to suggest that the hordes of youngsters buying LPs from Tesco and Urban Outfitters are impacting the classical market; format trumping musical content remains the preserve of a tiny sliver of audiophiles who are as happy listening to Beethoven as they are comparing recordings of train whistles.

Remarkable as it might seem, there are still those rare occasions for which the industry is willing to put ideology before profit. When the British-German composer Max Richter signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon in 2014, it was on the condition that albums of his works were released on vinyl: DG was effectively forced into pressing its first frontline (as opposed to reissue) vinyl material in years through artist will rather than market strategy.

Richter’s feelings about the format echo those of many self-confessed analogue music enthusiasts, but they also hit upon some of the most vital opinions tapped into by Milner in his book: that digital-capturing techniques like Pro Tools have sucked as much life from the process of recording as they have from the results in playback. But what he and the vinyl lovers miss most from our brave new digital world is ‘presence’ – the elusive sonic quality that many claim the CD never managed to bottle. ‘There’s just something very sterile about a CD – this arid noise that comes out of it,’ says Richter. ‘I found that very difficult to warm to.’ Don’t take just his word for it. Milner’s book includes multiple erudite opinions straddling both sides of the analogue/digital divide. But perhaps its most fascinating episode is an encounter with the tantalising character that is Dr John Diamond, a pioneer of holistic healing who believes digital music can be held accountable for much of the world’s misery, angst and violence.

Diamond’s thesis is rooted in science he claims to be able to prove. But when Richter and so many others talk about the ‘sound’ of analogue music, their language is more romantic. ‘We have this collective memory of what vinyl sounds like and we associate it with the great music of the past,’ the composer says. ‘Many of us will have encountered Mozart, Beethoven, Bach and The Beatles through the medium of vinyl. It has a specific sonic signature and I think that becomes inextricably linked with that repertoire.’ You can see why his own work, with its roots in past sounds and its certain wraparound, spatial presence, might have found a natural home in this format. Richter maintains that his vinyl recordings are for core fans who followed him long before he signed to DG. But the Yellow Label is pushing vinyl’s emerging ‘hipster’ factor with Richter: it recently released excerpts from the composer’s work Sleep on 180g transparent vinyl, the ultimate in turntable chic.

Encountering opinions like Diamond’s and Richter’s can set you on quite a path. Particularly if, like me, you came to maturity listening to classical music via digital means. I bought my first turntable after reading Milner’s book, and the first record I played on it was Sony’s 2014 recording of Le nozze di Figaro from Teodor Currentzis. I felt the shock of that ‘presence’ from a recording made digitally but rendered by a stylus vibrating in a groove. And yes, it does sound different. There’s an embracing quality and a certain spatial clarity, despite the sonic limitations that are imposed on the recording to stop the stylus jumping out of the groove (something like MP3 compression, but nowhere near as indiscriminate or bland). The question is: was I hearing the music, or hearing the recording?

It’s a longstanding paradox that classical music – strewn with silences, encompassing a wide dynamic range and featuring unending variations in texture and colour – should be linked to a medium as inaccurate, as ‘low-fi’, as vinyl; a medium in which you hear the mechanism of the reproduction at all times, absolutely not as music is heard in the concert hall. While this is fine for Richter’s scores with their ambient halo, it’s not so good for an Enescu symphony in all its horizontal complexity. As for that mechanical noise, is it the fuzzy course of the needle that we talk of when we describe the ‘warmth’ of a record’s sound? Not if you speak to the people at Linn Records, who claim that their customers are constantly upgrading their systems to mitigate that noise.

I felt compelled to ask Greg Milner, who steers a central course through the choppy analogue-versus-digital waters in his book. ‘I’ve discovered in my own listening that acoustic instruments sound a lot better through analogue means,’ he tells me on the phone from his home in New York. ‘I don’t know what it is, but they just do.’ In the final pages of his book, Milner recounts the experience of recording his own voice on a wax cylinder using an 1889 Edison lathe. He makes a powerful observation: that the uneasy feeling many of us experience on hearing our own voice played back through a digital recording – is that really how I sound? – has gone.

The arguments around sound quality will spin round and round just like the old acoustic-versus-electrical dialectic that occupied Edison and his competitors. Proponents of digital music will ‘prove’ scientifically that there’s no competition between the two formats while analogue fans will dismiss those experiments as irrelevant, measured against the wrong scales. Meanwhile, the rest of us appear to have moved on; we’re talking less of analogue versus digital and more of convenience versus ceremony – an argument in which we appear to want a bit of both, throwing a very precarious light on our old friend the compact disc. ‘There’s a spectrum here,’ says Richter. ‘At one end you have high-resolution files, which sound good and are convenient. At the other end, you have the very inconvenient but wonderful-sounding vinyl. And in the middle, you have the CD, which is neither convenient nor wonderful. So the CD is over. Finished.’ Milner has a different slant on much the same sentiment: ‘If anything, vinyl has more relevance now than the CD does,’ he says. ‘And that is something I definitely didn’t see coming.’

Is that why labels big and small are bending over backwards to nurture the tiny market that is vinyl, with its splendid immunity to the havoc visited upon unit sales by digital downloads and streaming? Research from the industry body in Britain, the BPI, colours the picture a little more subtly. Two thirds of music consumers consider themselves ‘multi-channellers’, says a report from the BPI published in December, meaning that they stream music using the likes of Spotify and Qobuz before buying selected favourite albums on CD or, increasingly, LP. There is a new desire among music fans ‘to emotionally engage with the recording and the cover artwork it comes with’, it is suggested. The BPI threw its weight behind this perceived new desire when it launched a chart for vinyl sales to coincide with Record Store Day in 2015. But for many of us classical collectors, that ‘desire’ is anything but new.

The vinyl chart might be little more than a marketing tool, but what looks interesting is the loosely definable ‘art music’ or ‘classic album’ make-up of a higher-than-usual proportion of its listings: albums bought by people whom you might presume place a certain value on focused listening. Richter sees the vinyl trend, as a whole, as ‘an immune reaction against the virtualisation of art and culture’. As he claims, ‘There’s something about the haptic quality of holding an object in your hand that embodies and contains the work. We are physical creatures and we can’t really get past that.’ Sure. But isn’t the size and shape of a CD even more satisfying than that of a cumbersome record?

That might be a controversial statement. But just as the ‘original’ vinyl lovers have felt the need to rally around their beloved format as it faced extinction in the face of the cassette and CD, so Richter’s talk of the demise of the CD can induce feelings of protection in those of us who were ensnared by the art of music in the time just before the CD became mainstream. I’m not sure there’s anything immediately more satisfying about a cardboard vinyl sleeve – prone to bending, tearing and scuffing – than there is about beautiful CD artwork, sitting resplendent inside a shiny jewel case. The only physical difference, perhaps, is psychoacoustic: the fact that you see your LP turning; that – in theory – you can even see the music cut into its surface.

Ultimately, it’s that ritual of playing the music that appears to be behind vinyl’s comeback. Unsheathing the record, placing the stylus, flipping to the B-side – all this requires a certain amount of devotion, representing a homage to those who created the performance, even the music itself. ‘For our customers, it’s about taking a record, placing it on the turntable, sitting down with a glass of wine and enjoying the listening experience,’ says Linn’s Kim Campbell, and it is an argument you hear time and again. In an age of total accessibility, vinyl poses a tantalising invitation to those of us who value concentrated listening, irrespective of opinions on sound.

So what of Milner’s ‘crowd forced on to a reservation’? Does that crowd now have the ear of the record industry, or even the music-consuming public? ‘I’m sure vinyl has a future, but I’m not so sure it’s anything to bank on,’ the author says. ‘When I wrote the book, I thought it was amazing that you could carry thousands of songs around in your pocket. And now, with streaming, I can own something like 90 per cent of the world’s music – that is, if “owning” means listening to it whenever I want. I will go to my grave thinking that vinyl sounds better. But I’m sure that for the last years of my life I will have listened to more digital music than analogue music.’

Milner is not alone. And if the BPI’s research is correct, cross-media music consumption is the future. Perhaps the most encouraging signal we can take from the miniscule but growing vinyl market is that musical curiosity and a penetrative attitude to listening are qualities that are still valued, and might even be on the up. Many readers will remember the days of subscription-CD purchasing through music clubs, a model which has sprung back into life off the back of vinyl’s resurgence. A new breed of vinyl ‘clubs’ will despatch a curated batch of art-house, limited-edition LPs to your door once a month (with a classical slant, if you so desire); members simply have to entrust their aesthetic tastes to the judgment of a stranger rather than putting their faith in ads and airplay.

But there’s a string attached – and it’s a digital one. Many of those records come with numerical codes that also allow you to access the music in digital form via your computer. In terms of company-customer satisfaction, it’s a win-win: the label already has your money and the download mechanism costs next to nothing (Amazon got wise to the economics of this early on with its ‘Auto-Rip’ service) while we get to hear our music in more than one room. It has taken a music industry in dire straits to prompt this buy-your-cake-and-eat-it attitude. And on the basis of that model, why not, like the Scientologists, squirrel away permanent records rather than transient CDs – even if you prefer digital sound? ‘I absolutely love vinyl,’ says a glowing Barry Holden as I leave him in his office, surrounded by the decorative sleeves of his latest releases. ‘There’s a magical warmth to the music that comes out of a record. It’s incomparable. But it’s never going to work in my car.’

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, the world's leading classical music magazine, please visit: magsubscriptions.com