Beethoven's Fidelio: a complete guide to the best recordings

Mike Ashman

Monday, November 16, 2020

In the composer’s anniversary year, Mike Ashman seeks out the finest recordings of his revolutionary operatic masterpiece

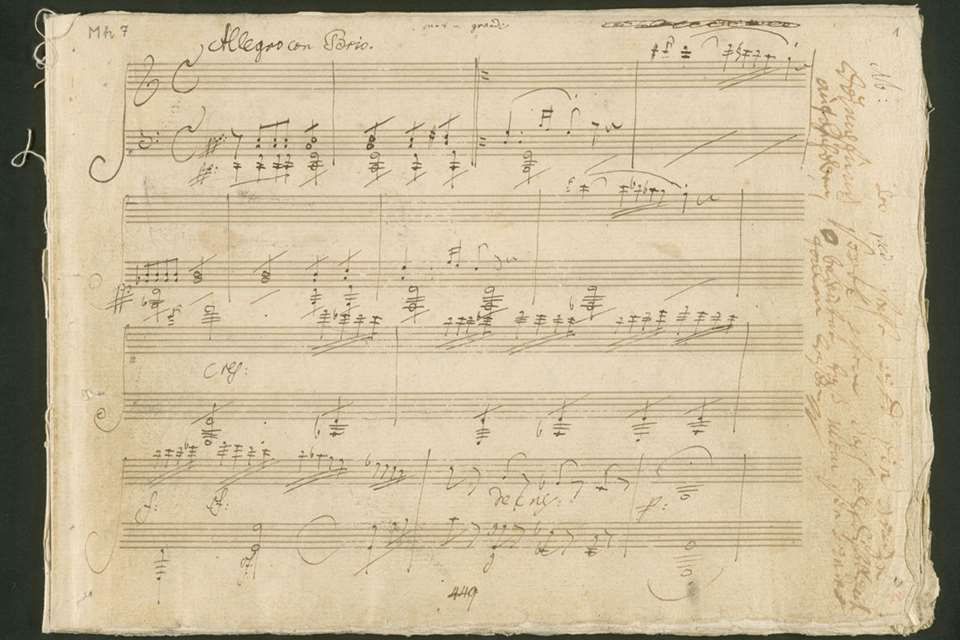

Both before and after the three differing versions (1805, 1806 and 1814) of Fidelio he tried out, Beethoven practised writing opera in extenso, taking lessons from Salieri (although fiercely rejecting his criticism of the eventual product) and starting a first full-scale opera, Vestas Feuer, in collaboration with Die Zauberflöte librettist Emanuel Schikaneder. But, dismayed to discover from the latter’s drafts that ‘Rome’s holy vestal virgins spoke with the tongues of contemporary Viennese shopgirls’, Beethoven took refuge in the winter of 1803/04 in J‑N Bouilly’s Léonore, ou L’amour conjugal. Written for one of the Paris companies of the Revolution period, the Théâtre Feydeau – whose repertoire of, literally, ‘music-theatre’ demanded a new brand of actor and singer in one – it was already a success in Revolutionary Paris as set to music by actor/singer Pierre Gaveaux and was currently being worked on also by Ferdinando Paer and Simon Mayr.

The form and style of Beethoven’s own Leonore/Fidelio project (he always preferred the heroine’s name as title) was influenced by the contemporary French operas – the work of Dalayrac, Méhul and Cherubini – in which he had played viola in the Elector of Cologne’s court orchestra between 1789 and 1792. Like these, Fidelio was in two-act opéra comique form, a ‘rescue’ opera alternating spoken dialogue with a formal succession of set-piece arias and ensembles.

Beethoven was to extend both ‘rescue’ opera tradition and Bouilly’s libretto. Pizarro (a spoken role in the French original) was allowed a large-scale aria of remorseful self-examination, a marker for the later Romantic monologues of Weber’s demons (Kaspar in Der Freischütz or Lysiart in Euryanthe) or of Wagner’s tortured Holländer and Telramund. Beethoven also demanded from his Viennese librettist Joseph Sonnleithner an actual text for a scene (imagined to be offstage in the Bouilly) where Rocco is bribed to help with Florestan’s murder. He set this to music as a duet, and also gave Leonore a large-scale aria and recitative (the last added only in 1814), another forerunner of later 19th‑century music drama.

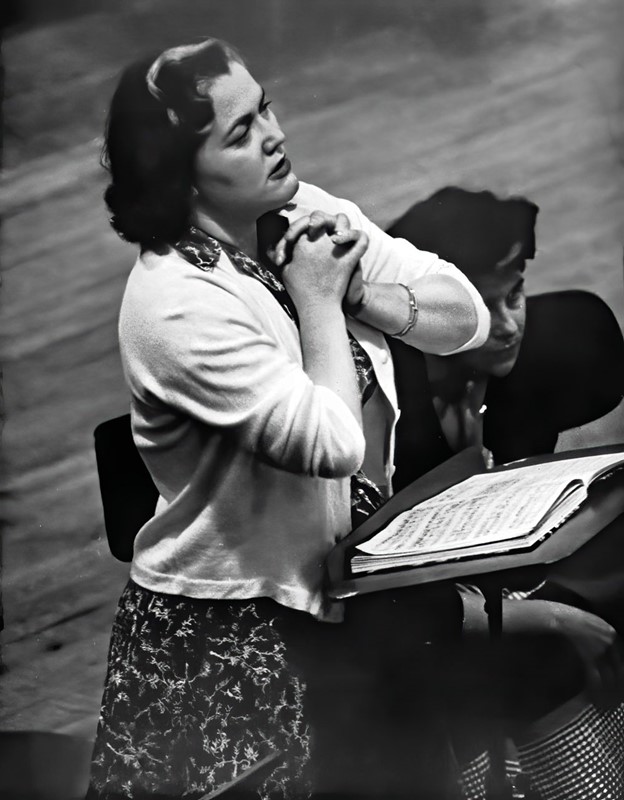

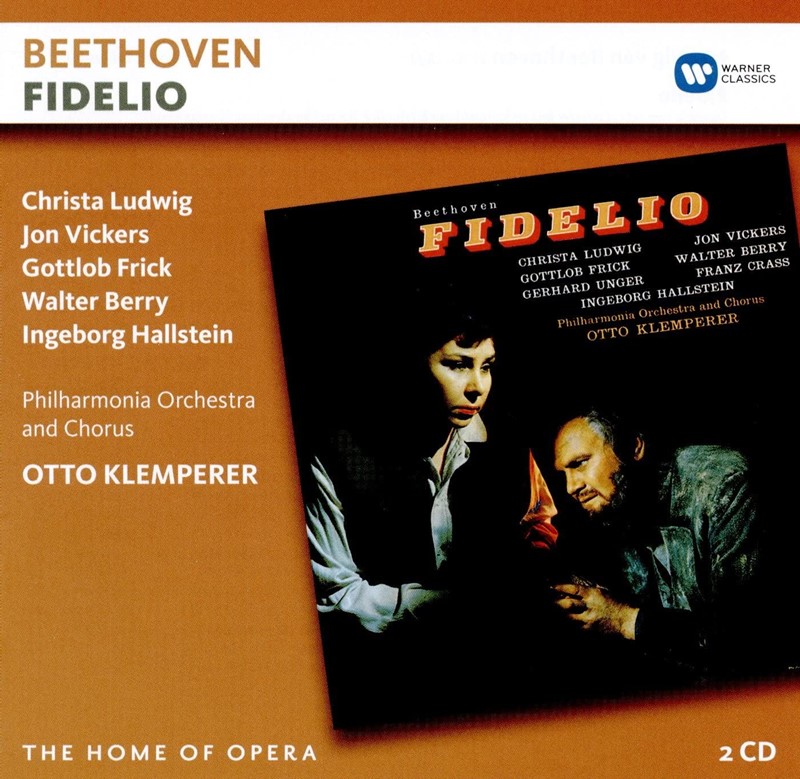

Kingsway Hall, 1962, under Klemperer: Ludwig, Vickers and, second from right, producer Walter Legge (Brian Seed / Bridgeman Images)

Beethoven sought to maximise the effect of Bouilly’s drama by setting most of it to music (its other composers stayed with the spoken word): the gravedigging duet with its eerie bass; the trio of hope (‘Euch werde Lohn’); and the apocalyptic Quartet where Leonore’s hidden pistol and the announcement of minister Fernando’s arrival spare Florestan’s life. Then, harnessing music from the abandoned Vestas Feuer (for the ‘Namenlose Freude’ duet) and stylistic tropes from his own early Cantata on the Death of Joseph II and Christ on the Mount of Olives, Beethoven – for his 1814 edition – constructed a mixed‑form finale.

A Salieri-style deus ex machina – Minister Fernando arriving like a Baroque god to solve mortal problems – was followed by a (French) Revolutionary cantata with shades of Méhul and Gossec. It represented a huge staging challenge to conductors and directors who had already to carry an audience in a single work from music and images suggestive of the low comedy of Rocco’s domestic concerns to those of the Day of Last Judgement. Like Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (which Beethoven so admired), Fidelio remains difficult to perform, and sometimes to appreciate, precisely because of this abrupt mixture of contrasting theatrical elements – ‘the everyday and the marvellous’, as Michael Tippett once neatly termed them.

Fidelio on disc

The history of Fidelio on record or film is a strange one, even suggesting the loss of a tradition or, more recently, of confidence in the work. Decades have slipped by without the official major recordings that one might have predicted. Its discography easily becomes a history of past rather than present achievements. Expect, also, to find here varying amounts of dialogue or substituted narration, and either the absence or presence of Rocco’s Act 1 ‘Gold’ aria and the Leonore No 3 Overture which, since the early 19th century, has been often inserted into Act 2 – either as a useful scene-change cover or to show off conductor and orchestra.

Bruno Walter conducts the opera idiomatically like the opéra comique it is: changing styles in an instant and avoiding the fabrication (Furtwängler-style) of neo-Romantic links that simply aren’t there. There are big names in Walter’s cast – Kirsten Flagstad, Alexander Kipnis (Rocco) and Herbert Janssen (Fernando) for three – but it is Walter himself who provides the reason for collecting this performance in a 1941 sound cured but still dated. Flagstad manages the showpiece recit and aria ‘Abscheulicher’ and the Act 2 heroics with predictable impact and weight of tone. But, like many of her contemporaries, she sounds determined to make the deliverance of her husband solely a spiritual thanksgiving. You forget the human side here (Anja Kampe’s more truly acted Leonore in the 2014 Daniel Barenboim/Deborah Warner La Scala telecast offers a good corrective). Yet in the 1941 finale Walter creditably holds out for an opéra comique’s weight, tempos and balance rather than a Missa solemnis’s.

Arturo Toscanini’s performance naturally demands attention for his achievements as a Beethovenian and experienced theatre conductor (can it fulfil the promise of a pirated radio Act 1 in nigh-on impossible sound from pre-war Salzburg?). Of course his conducting is detailed and exciting, yet the boxy, airless sound and uneven casting get in the way. The cast includes Rose Bampton, Jan Peerce and Herbert Janssen (as an under-evil Pizarro) but they do not compensate as actors of the text for the lack of dramatic focus in their singing. It’s a duty of love rather than a properly realised show.

Kaufmann and Pieczonka in a shadowy 2015 Fidelio from Salzburg under Welser-Möst (Monika Rittershaus / Unitel / Sony)

Under Wilhelm Furtwängler, tempos seem purely subjective, governed by his mood – they’re often slow (or, at least, starting slow) with pauses/fermatas guiding the overall line. Most excitement has been focused in the past on the combination of Kirsten Flagstad and the clever tenor Julius Patzak (an especial master of text) in 1950 live from Salzburg. But, rather as in the case of the two Furtwängler Ring recordings, it’s a less famous cast – 1948 with the underrated Erna Schlüter as Leonore, Furtwängler favourite Ferdinand Frantz as Pizarro and Otto Edelmann other-wordly as redeeming minister Fernando – that provides the more dramatic performance, if less used to the infamous Furtwängler beat and hence rougher in terms of ensemble.

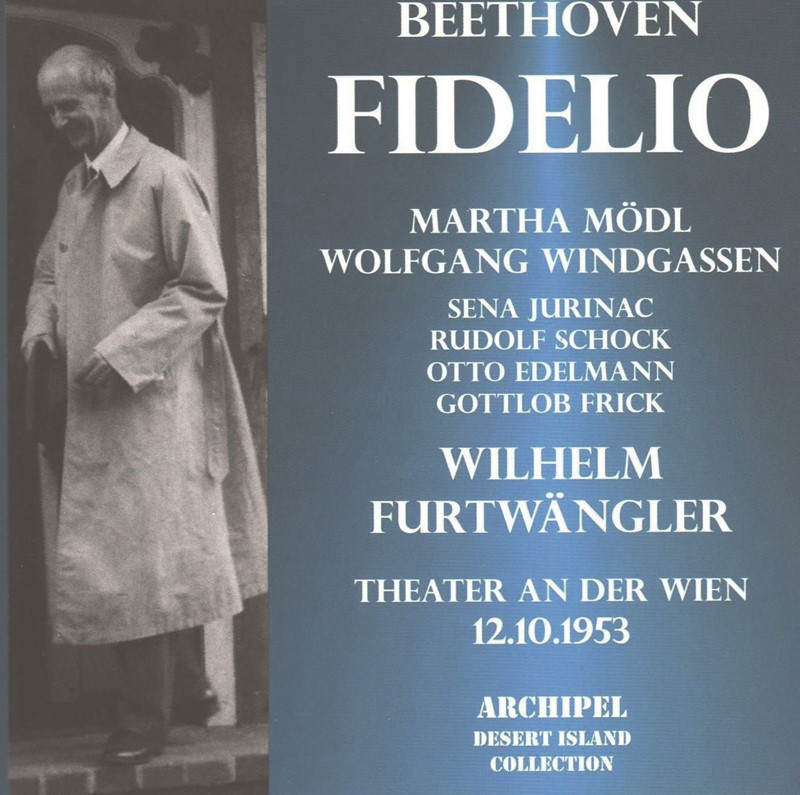

Also exciting is the live performance in October 1953 that trailed a first studio EMI recording. Martha Mödl is one of the 20th century’s most versatile Leonores in her ability to convey side-by-side fury and tenderness in ‘Abscheulicher’. You can really hear Leonore’s distraction at the first sight of Florestan in the gravedigging duet with Gottlob Frick’s plain-man Rocco (a well-worked contrast to his villainous or comic roles). Furtwängler’s spooky basses and wind accent the accompaniment like the clash of a spade’s metal on stone and earth. Windgassen’s early Florestan has spirited resistance as well as fear, and eschews the sentiment that heavier voices often drag. Otto Edelmann has become a noble yet evil Pizarro. This is more worth acquiring and noticing than the dialogue-less studio version.

Comparing Erich Kleiber’s radio broadcast to live work from leading contemporaries makes his Fidelio, as presented, seem dated. The bore of a narrator – maddening after frequent repetition, not to mention the stylistic clash with other ultra-realistic spoken dialogue – takes us to the university lecture room rather than the theatre. Late-coming guest Birgit Nilsson (surprisingly often out of tune), bullish Hans Hopf and the ubiquitous Paul Schöffler’s Pizarro make only workmanlike contributions. Kleiber, however, like his sometime colleague Clemens Krauss, manages never to blow up the emotions into grand opera. The bleak fanfares that introduce Florestan’s Act 2 dungeon, the climaxes conjured up for Pizarro’s attempted murder or the chorus’s final entry confirm this conductor’s theatre-hardened grip on what the music is describing. But those mixed-up narrations and neutral singers’ contributions water down dramatic impact.

To date, so far as Fidelio is concerned, historically informed performance has been exclusively the preserve of those excavating the two earlier versions of the work under the title Leonore. We’re not discussing those here but René Jacobs, John Eliot Gardiner and Marc Soustrot will take care of your needs for 1805 and 1806. But Ferenc Fricsay’s 1957 recording still sounds much like a bolt from this blue, with its slimmed-down orchestral weight and Mozart-scaled approach from the singers. Using relatively quick speeds and no 19th-century dynamics, Fricsay frames a fluent, emotional Leonore (Leonie Rysanek), a martinet-like threatening Pizarro (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau) and a lyrically sung and not Heldentenor‑ish Florestan (Ernst Haefliger). Only the misplaced ambition to record ‘real’ actors in the dialogue instead of singers gets in the way. The vocal jump alone from Pizarro/Fischer-Dieskau to Pizarro/actor in the character’s first scene in Act 1 should have put that idea out of the producer’s head.

Karajan and Klemperer

Herbert von Karajan’s first ‘official’ recording (Warner, ex-EMI) – five others have been issued so far – proved less of a compelling new look than a dutiful revival. From a recent tranche of Salzburg Wagner recordings Karajan carried forward Jon Vickers (the drama of extremes as ever but better joined up earlier under Klemperer), Helga Dernesch (never quite the emotional equal of earlier guest Scottish Opera performances), Helen Donath (almost too weighty a Marzelline after her Meistersinger Evas), Zoltán Kélémen (as Pizarro – a part that has attracted many Wotans here at last gets a successful Alberich) and Karl Ridderbusch (a pointlessly more noble-sounding Rocco). There’s also a live Vienna recording – long pirated, now adapted by DG: stronger meat altogether, although Vickers (singing through illness, although some have denied it’s actually him) sounds strange at times. With Christa Ludwig as Leonore and Walter Berry as Pizarro the cast is virtually tracing out a copy of Walter Legge’s studio version – with, as often happened, Karajan taking tips from his one-time producer.

The pair of Otto Klemperer recordings – one, the Testament, from an ROH broadcast – capped off, for an old Fidelio hand, acclaimed 1950s London symphony cycles with the Philharmonia. Excitement about the live performance – actually two were preserved – was felt for a cast apparently preferred by Klemperer to Legge’s studio roster: Jurinac’s experienced, feminine and moving Leonore, Hotter’s far from merely evil demon Pizarro (his dialogue is exceptional too, and Klemperer allowed them all much more than Legge) and the vice-like grip of Covent Garden’s orchestra and chorus on Klemperer’s unfamiliar beat. But for Columbia, now Warner, Klemperer (together with Legge’s studio nous) obtained another, completely separate reading – but a strong one, beautifully cut together. At nearly 60 years old it’s still a leader in the field. And this despite the risks of a debutant Leonore who was a mezzo, a Pizarro who seemed more character singer than principal villain (but remember Berry was on the way to Wotan for Karajan and trying out Sachs at Bayreuth), and a Marzelline who needed a dialogue actress (they chose Elisabeth Schwarzkopf!). As for Testament, Jon Vickers delivers an excellent and, on the whole, unmannered Florestan.

Rysanek: an emotional Leonore for Fricsay (1957, Tully Potter Collection)

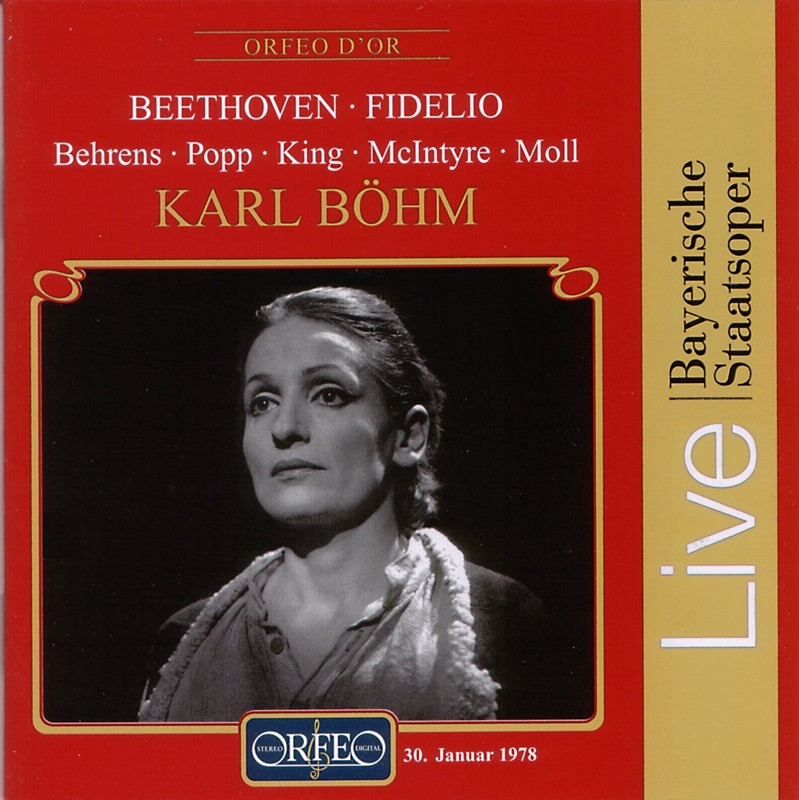

If you’re keeping track of recordings, Karl Böhm, with 11 traceable including a video, must count as a Fidelio obsessive. James King was often his Florestan, less expressionist than Vickers but a sincere conveyor of experienced grief and family heartache. His DG Leonore is Gwyneth Jones in one of her best roles. A few vocal insecurities are swept aside in a flood of righteous passion. The Staatskapelle Dresden have the score massively in focus although the chorus prisoners get to sound almost indecently buoyant. Almost a decade later, from a staged performance in Munich, Böhm – always a collector of new stars – had placed the then Leonore of the moment, Hildegard Behrens, alongside the more familiar Donald McIntyre’s Pizarro (another Wotan dominant in this role, but one not afraid to show worry) and Kurt Moll’s steadily conventional Rocco. And there’s still a spring in Böhm’s conducting step – it’s hardly touched by historical research but it lovingly conjures up the opera’s place and space, matching a Götz Friedrich staging that aurally impacts on the performers.

Leonard Bernstein oversaw a less specifically worked-out RAI performance with Birgit Nilsson in 1970 (issued in Nilsson’s ‘Great Live Recordings’ box-set – Sony, 10/18), but with the 1978 Vienna cast – also once on DVD in Otto Schenk’s generalised staging – he presents clearer musical ideas. A picture-book gentleness informs the early Rocco scenes, then dynamics and seriousness increase as the opera’s do. René Kollo, both an intelligent worker with words and actor of unhackneyed passion, is an apt partner for Gundula Janowitz’s smaller-voiced than usual but equally text-conscious Leonore. Fischer-Dieskau’s grandly acted Fernando is every inch an official in his dealings with the ‘poor people’ and shows (as not so often occurs in these recordings) a clear emotional response to the discovery of Leonore and Florestan.

Digital Fidelios

Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s Fidelio is both smaller-scaled than grand and precisely rehearsed with a high-class chamber orchestra and chorus. Margiono and Seiffert, again of less tonal weight than one used to expect, present detailed readings of their roles’ emotional range. There are one or two tempo eccentricities characteristic of this conductor: the perversely slow speed for ‘O namenlose Freude’ turns the duet into two private asides rather than a joint celebration. (The conductor does the same in a rather dull Zurich video a decade later in which a young Jonas Kaufmann and a strikingly period male-made-up Camilla Nylund, again of a lighter voice than one might expect, are creditable soloists.)

The Michael Halász set with Inga Nielsen and Gösta Winbergh is one of Naxos’s little miracles – a ranking cast on good, keen form assembled at budget price. Halász accompanies with a high-class chamber orchestra and a definite ear for historically informed practice. Especially given the lack of up-to-date modern competition, this is a serious contender.

The Simon Rattle and Claudio Abbado sets have been the only relatively recent ones featuring leading conductors of today. The Abbado is cast from a starry roster – although Stemme was only just starting in the role and Kaufmann was at the beginning of a move towards heavier parts. Fischesser’s Rocco (who, regrettably, gets to speak much of the Act 1 dialogue as if he were the narrator) and Falk Struckmann’s Pizarro are solid rather than exceptional. Abbado’s musical direction doesn’t quite match the searching vision or the touch in scaling down accompaniments that distinguished his Mozart operas – although the Mahler and Lucerne orchestras make an effective joint ensemble. But it’s not the set for modern times that it could have been.

Nor is the Rattle, from a live April 2003 concert following staged performances. Everything is crisp and smacks of its class but seems to have not yet reached a wholesale understanding of or sympathy for the piece. The dialogue is poorly cut and feels like it was added later, rather as the 1950s would have done with a team of actors; stage production has left no compelling vision of the piece with the cast. Magical little touches flash through occasionally to remind us of the quality of the participants – the timpani at the start of ‘Ha! Welch ein Augenblick’, an accent, or a pause leant on – but overall it remains unfinished work in progress. The soloists, perhaps an unpredictable line-up for the time, haven’t combined well.

Fidelio on film

Many of the not large number of Fidelios available for the small screen seem to focus on the less extreme productions. As the 1970s turned into the 1980s, Bernard Haitink worked with a Leonore who, even less than a generation before, might have been considered vocally on the light side. In Peter Hall’s tidy, relentlessly logical Glyndebourne staging (first released on video in 1979), Elisabeth Söderström shows off the watchable detail and focus on colleagues that distinguished her Jenufa and Marschallin. Haitink often leans towards a gentler, more formal side of the music drama but the orchestra, with whom he had completed a Beethoven symphony cycle a few years before, have absorbed his precise way with this composer.

A completely other route was taken in Salzburg in 2015 when Franz Welser‑Möst and Claus Guth presented the opera as a pageant of Freudian symbols with sound effects replacing dialogue and many characters doubled by shadows. Brilliantly achieved performances by Adrianne Pieczonka and Jonas Kaufmann help the quite frightening non-naturalistic medicine go down.

The most recent small-screen Fidelio comes from Covent Garden this year and both its initial run and its cinema release were interrupted by Covid-19. Broadcast on BBC Four at the end of July and since acquired by Apple Music (with plans for a future DVD release on Opus Arte), it sees Antonio Pappano conducting (with a well-balanced range of emotion and style) a strong cast featuring the new star Lise Davidsen as a most credible Leonore especially strong at the top of the range and in rhythmically awkward passages. Tobias Kratzer’s production commutes from a conventional 1960s-style staging of Act 1 to a more abstract Act 2 with all the chorus on stage and on TV screen throughout, and the dungeon represented by a rocky outcrop. Expect short dialogue additions from Messrs Grillparzer and Büchner, and surprising extra involvement from Marzelline. Rather like last year’s Bayreuth Tannhäuser from Kratzer, some of these ideas seem like work in progress but overall it’s certainly fresh and original.

This pick of currently available Fidelio recordings focuses almost totally on those which treat the opera as it was written – as an opéra comique. This vital balance of speech, lower-life comedy and higher-life danger (if not quite tragedy), however it is presented visually, makes the 1814 version the success it is. It’s precisely the lack of this balance that has promoted so much modern tinkering to ‘improve’ the work from a wrongly perceived status of good music/bad drama. The list of conductors who have missed the mark on disc is long and distinguished. It includes Solti, Colin Davis, Maazel and Barenboim, all of whom ironically enough have/had more than regular experience of conducting in the opera pit. Solti’s Chicago set – the first digital recording – feels like a high-class exercise in ensemble. Of Maazel’s two recordings, the first – for Decca, and often praised in these columns – lacks flesh-and-blood emotion in its central relationship, interesting and bold though the casting of James McCracken was. Davis seems unsure (on his first RCA recording) whether to borrow the weight and space of Klemperer or (with the LSO) to attempt his version of historical performance not unlike his Handel. Barenboim on relay from La Scala (commercially nla) makes more sense than his recording, which is upstaged by Waltraud Meier’s narrations.

The selection here has been limited also by the present bias towards the older in extant recordings, and also by a low level of availability (this opera’s discs have never been long-term catalogue occupants). But the world still needs a good modern Fidelio on disc as well as a period-informed one.

The Modern Choice

Hálasz

Naxos

When Naxos assembled an almost surprisingly starry cast, the performance really took fire. Nothing bargain-basement here, from the great sense of style and period scale achieved by this Florestan and Leonore and their distinguished colleagues, to Michael Hálasz’s alert conducting. Inga Nielsen in particular shows how effective a more lyrical Leonore can be.

The Well-Balanced Choice

Böhm

Orfeo

You can trace Böhm’s Fidelio on disc back to wartime Vienna. This live one from January 1978 is the most recent (of 11!) to appear. The conductor’s gentle touch and subtle steering make this an object lesson in achieving the piece with modern instruments and balance. The strong and experienced cast includes Lucia Popp as an ideal Marzelline.

The Historical Choice

Furtwängler

Archipel

Really this choice is a tie but the 1941 sound on Bruno Walter’s Metropolitan Opera set is just that bit too faded. Furtwängler spent a lot of his last six years using Beethoven as proving ground for his philosophical and compositional theories. A thrilling evening in the theatre with Martha Mödl, Wolfgang Wingassen et al.

The Ultimate Choice

Klemperer

Warner Classics

As in the symphonies, Klemperer in Beethoven – all wind, brass and drums – remains essential, as do his rhythm and feel for the drama. He was a great opera conductor. Good sound, too. You can have Klemperer live at Covent Garden on Testament, but with this set you get Legge’s studio magic as a bonus.

Selected Discography

Recording Date / Artists Record company (review date)

1941 Flagstad, Maison; Metropolitan Op, New York / Walter Guild GHCD2269/70; Naxos 8 110054/5 (4/00)

1944 Bampton, Peerce; NBC SO / Toscanini RCA GD60273 (10/56, 10/92)

1948 Schlüter, Patzak; VPO / Furtwängler Wallhall WLCD0149

1953 Mödl, Windgassen; VPO / Furtwängler Archipel ARPCD0181-2

1956 Nilsson, Hopf; Cologne RSO / E Kleiber Capriccio C67 186/7

1957 Rysanek, Haefliger; Bavarian St Orch / Fricsay DG 453 106-2GTA2 (10/58, 5/93)

1961 Jurinac, Vickers; ROH Orch / Klemperer Testament SBT2 1328 (2/04)

1962 Ludwig, Vickers; Philh Orch / Klemperer Warner Classics 2564 69561-4 (6/62, 10/00)

1969 Jones, King; Staatskapelle Dresden / Böhm DG 477 5584GOH2 (11/69)

1970 Dernesch, Vickers; BPO / Karajan Warner Classics 948172-2 (4/71, 4/88)

1978 Janowitz, Kollo; VPO / Bernstein DG 474 420-2GOR2 (10/78, 10/03)

1978 Behrens, King; Bavarian St Op / Böhm Orfeo C560 012I (2/02)

1980 Söderström, de Ridder; LPO / Haitink Arthaus 101 109

1994 Margiono, Seiffert; COE / Harnoncourt Warner Classics 2564 63779-2 (10/95)

1998 I Nielsen, Winbergh; Nicolaus Esterházy Sinf / Halász Naxos 8 660070/71 (12/99)

2003 Denoke, Villars; BPO / Rattle Warner Classics 9029 57375-3 (11/03)

2011 Stemme, Kaufmann; Lucerne Fest Orch; Mahler CO / Abbado Decca 478 2551DH2 (9/11)

2015 Pieczonka, Kaufmann; VPO / Welser-Möst Sony Classical 88875 19351-9; 88875 19352-9 (A/16)