Mahler Symphony No 5

Rattle’s new Fifth is proof positive that the Berlin Philharmonic has made great strides with Mahler since Barbirolli

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Gustav Mahler

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Great Recordings of the Century

Magazine Review Date: 12/2002

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 78

Mastering:

Stereo

ADD

Catalogue Number: 5 67925-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 9 |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Gustav Mahler, Composer John Barbirolli, Conductor |

Composer or Director: Gustav Mahler

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: EMI Classics

Magazine Review Date: 1/2002

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 68

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: 5 57385-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 5 |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Gustav Mahler, Composer Simon Rattle, Conductor |

Author: Richard Osborne

Barbirolli’s 1969 Mahler Fifth already has its place in ‘Great Recordings’, and rightly so. The work is a terror to bring off but, brought off, is a joy beyond measure. It made a fine nuptial offering for Rattle and the Berliners on September 7 – festive yet challenging, a tragi-comic revel and a high-wire act to boot. ‘The individual parts are so difficult,’ wrote Mahler, ‘they call for the most accomplished soloists.’ I watched the television transmission slack-jawed as the principal trumpet performed dazzling feats of virtuosity without for a moment violating the tenets of good ensemble playing.

,BR>Rattle brought the prodigious first horn to the apron of the stage for his obbligato contribution in the Scherzo. Mengelberg’s conducting score, which Mahler used for the work’s Amsterdam première in 1906, has an annotation to this effect, and the practice was followed at the work’s English première in 1945, but I am left wondering what would have happened had Rattle not brought the player forward. EMI’s recording is splendidly explicit, but the horn section, which plays a crucial role at key moments in the symphony, seems oddly distant on CD.

The tutti sound Rattle draws from the orchestra is clean and sharply profiled, not unlike the Mahler sound Rafael Kubelík tended to favour. Like Kubelík, Rattle separates the first and second violins, a mixed blessing in the Fifth Symphony where Mahler exploits the use of an antiphonal layout in contrapuntal passages yet also experiments with the sonic possibilities of unison fiddles. On the other hand, I doubt whether Kubelík would have been as solicitous as Rattle is of the Berlin strings with their suave legato and potentially inaudible pianissimi. Rattle’s tempo for the Adagietto is a good one by modern standards (not too slow) and the string playing has a lovely diaphanous quality, but you may find the playing over-nuanced.

Over-nuancing was a problem with Bernstein’s early New York recording. As Deryck Cooke observed in July 1964, it should have been a much more moving experience than Bruno Walter’s surprisingly brisk and uninflected 1947 account with the same orchestra. In the event, the Bernstein was less involving, not more. Nowadays it is not unusual to hear rhythm and line sacrificed to detail and nuance as old-established symphony orchestras are made to re-think their readings by conductors schooled in the arcana of ancient performance practice. Rattle has done his fair share of this. What is interesting about this live Mahler Fifth is the degree to which the detail is absorbed and the line maintained.

Like most latter-day conductors, Rattle tends to underplay the march element in the first movement. Mahler in his 1905 piano roll, Walter, and Haitink in his superb 1969 Concertgebouw recording all preserve this. Some may find the approach too dry-eyed in the long-drawn string threnody at fig 2. But an excess of feeling can damage both opening movements (the second is a mirror of the first) if the larger rhythm is obscured. Rattle, like Barbirolli and Bernstein in his superb Vienna Philharmonic recording, treats the threnody more as a meditation than a march but the pulse is not lost and the attendant tempi are good. The frenzied B flat minor Trio is particularly well judged. The second movement is superb (the diminished horn contribution notwithstanding) and none but the most determined sceptic could fail to thrill to the sense of adventure and well-being Rattle and his players bring to the Scherzo and finale, even if Barbirolli (studio) and Bernstein (live) both reach the finishing line in rather more eloquent and orderly fashion that this talented but still occasionally fragile-sounding Berlin ensemble.As a memento, the CD is undoubtedly a triumph of organisation and despatch.

As a performance and as a recording, it has rather more character and bite than Abbado’s much admired 1993 Berlin version. Indeed, it can safely be ranked among the half-dozen or so finest performances on record. It is not perfect, but show me one that is.

Explore the world’s largest classical music catalogue on Apple Music Classical.

Included with an Apple Music subscription. Download now.

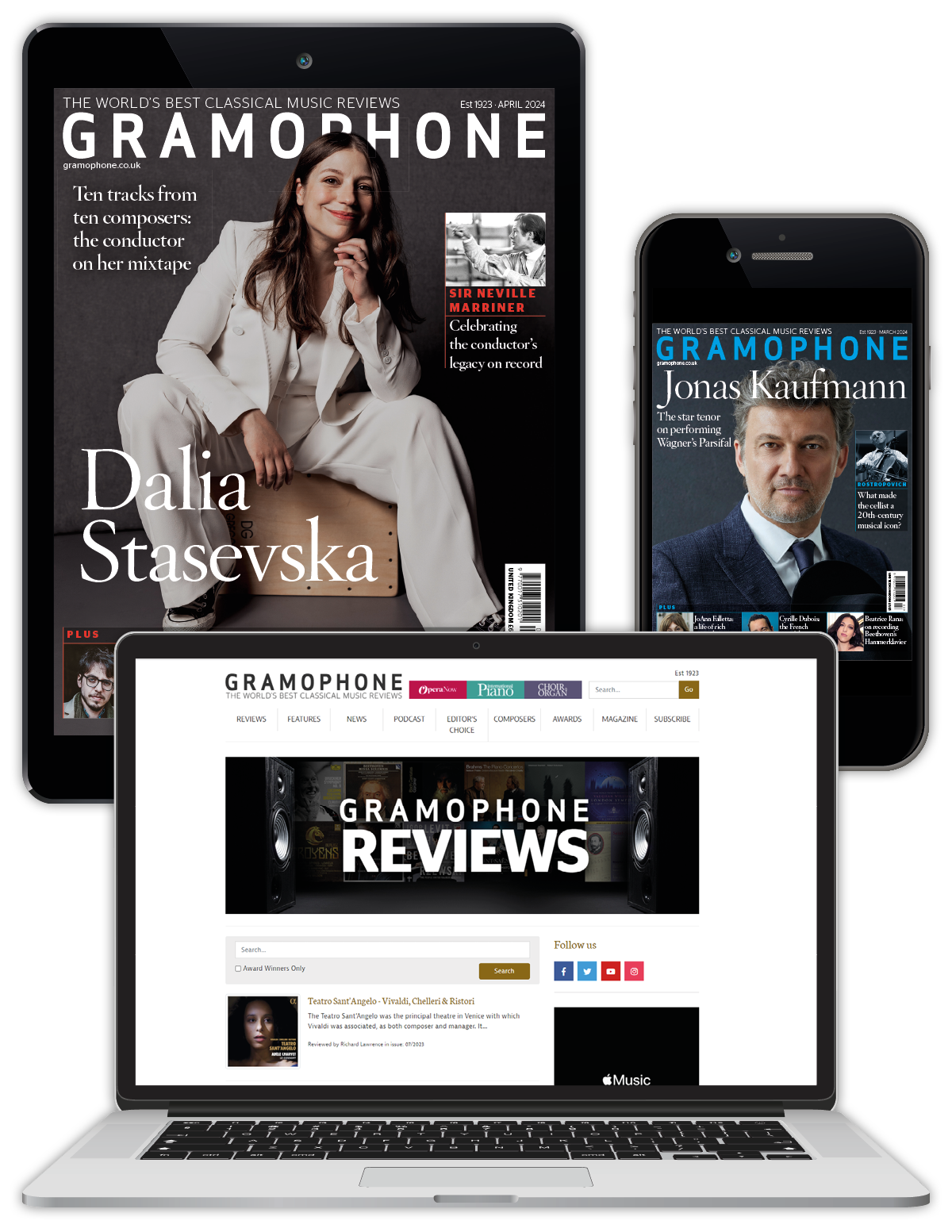

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.