Robert Helps - the musician's musician

Distler

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Spectrum Concerts Berlin have been responsible for some of the most interesting and valuable chamber events in recent memory, both in concert and via a series of CDs on the Naxos label. Their founder and director cellist Frank Sumner Dodge has especially devoted himself to the cause of the late Robert Helps (1928-2001), and if you happen to be in Berlin on May 12 and June 20th, you can catch two concerts largely devoted to Helps’ chamber music.

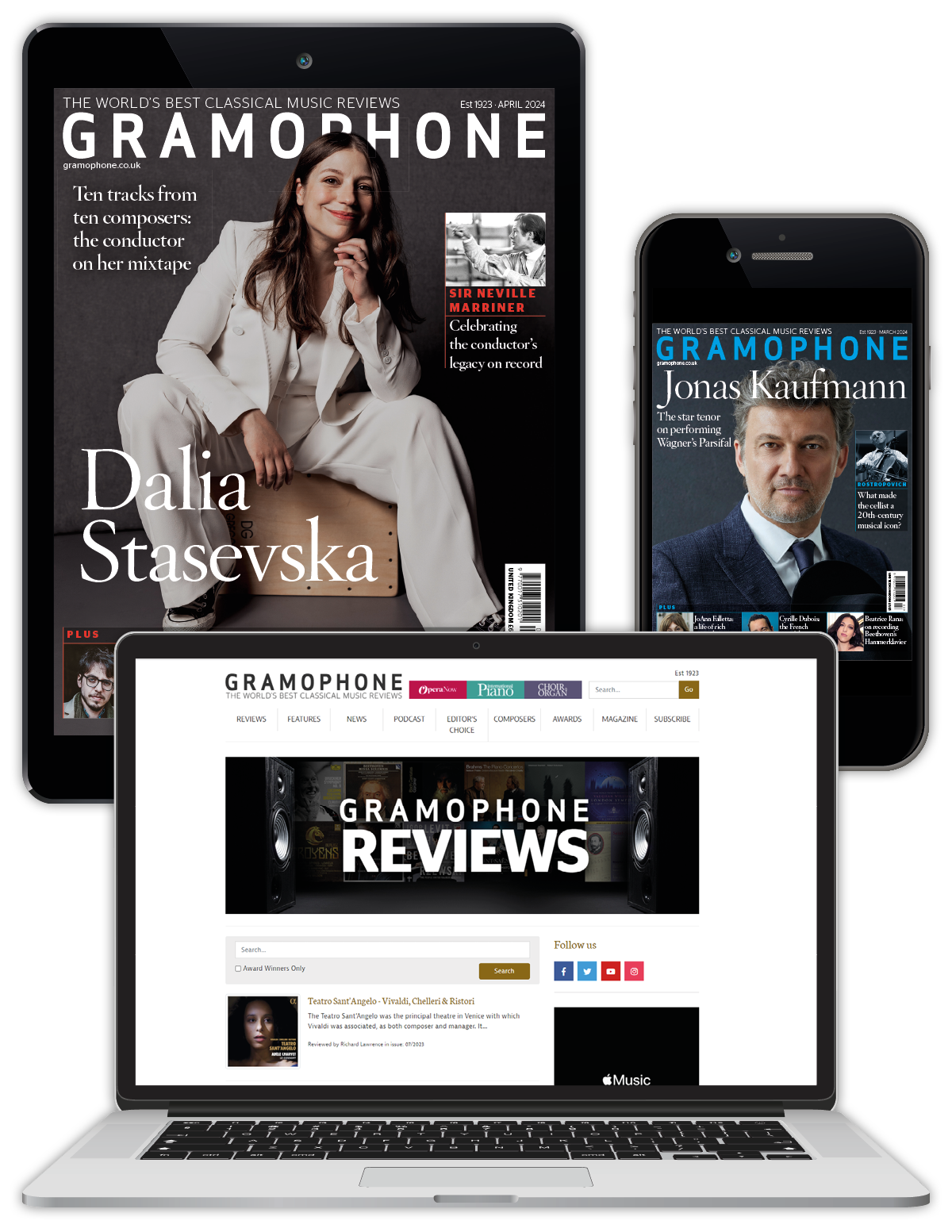

I mention this because Helps was a musician’s musician, and one of the most unique pianists in my experience. Back in 2002 I wrote a memorial piece about Bob that appeared in Gramophone’s North American Section, discussing his position among the coterie of American new music pianists who emerged in the late forties and early fifties alongside Paul Jacobs, William Masselos, Robert Miller and David Tudor. Although Helps’ compositional style was hard to pin down, looking back from a distance, it seems to stand as a kind of missing link between postwar serial trends and the New Romanticism movement that granted tonality its current lease on life.

Bob always credited his teachers Abby Whiteside and Roger Sessions as early and lifelong influences. Whiteside's theories of musculature and physical rhythm stood apart from the mainstream of piano pedagogy in her day. According to Whiteside, power and speed were generated not from the fingers alone but from the larger muscles of the torso and upper arms into the fingers: the fingers being the tip at the crack of the whip, so to speak. Whiteside aimed for a systematic coordination of torso, arm, and finger movements that would enable pianists to tackle difficult passages with fluency and physical economy, as well as freedom from stress and pain. Helps not only put these ideas into incandescent practice, but also passed them down to hundreds of students.

I didn’t study with Bob, but his longtime student William Komaiko suggested that I go and hear him play, which I did. It was an eye and ear opener. He’d sail through Sessions’ Second Piano Sonata (from memory), and shape it with unbelievable tone color and flexibility. We became good friends in the early 1990s. At our first get together, he sported a beard and long, flowing gray hair, sort of “Franz Liszt gone hippie,” entirely befitting Greenwich Village, where he'd stay during his infrequent trips from his Tampa, Florida teaching home base. I think we mainly bonded over a mutual obsession over historic pianists (he adored Friedman and Hofmann).

Certainly Bob wore his genius lightly. Showered with awards and commissions from the Guggenheim, Naumburg, Ford and Fromm Foundations and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Bob was loathe to promote himself, or play the publicity game. He exuded gentleness and charisma, and was an unfailingly generous colleague whose warm, gravely voice accentuated his sharp sense of humour. At the same time, he suffered serious bouts with depression that caused him to withdraw and cease communication with the outside world.

Bob paid no heed to trends and practical programming. Typically, he'd devote an entire recital to Sessions or John Ireland: box office poison. He once gave an all-nocturnes concert - from Gottschalk and Fauré (a specialty of Bob’s) to late Liszt and, of course Helps himself. Whenever Bob played, musicians showed up in droves. I attended his 1996 all-Sessions program at New York's Merkin Hall (also featuring violinist Jorja Fleezanis), and so did Milton Babbitt, Alfred Brendel, Elliott Carter, Garrick Olhsson, and David Del Tredici.

A year later, my organization ComposersCollaborative, inc. produced what proved to be Bob’s last New York recitals. He played the Chopin/Godowsky etude No 45 as an encore both times, and it was a revelation, with all of the elaborate polyphony crystal clear, gorgeously contoured, and judiciously spaced. Bob made many wonderful recordings, but this Godowsky selection is how I like to remember him, and I invite you to hear for yourself (Amazon).