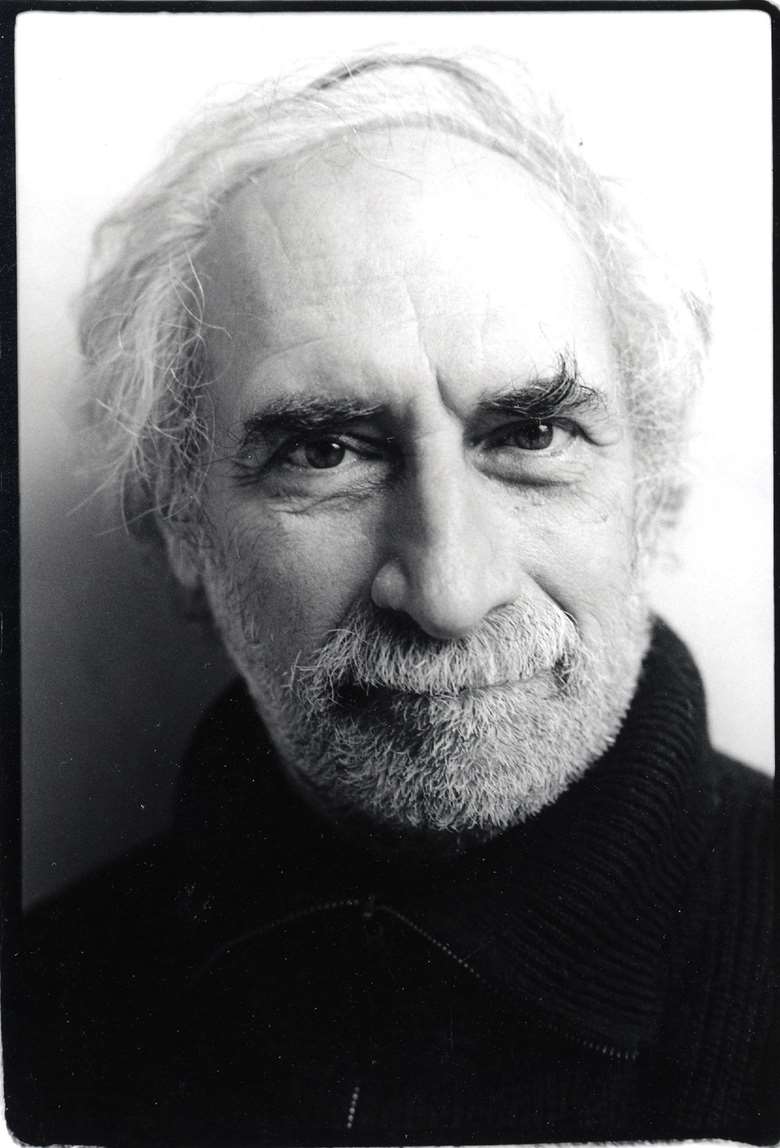

The American composer and pianist Frederic Rzewski has died

Saturday, June 26, 2021

Born April 13, 1938; died June 26, 2021

We learn of the death of the composer and pianist Frederic Rzewski. In tribute, we revisit a Gramophone 'Contemporary Composer' article written by Jed Distler and first published on our August 2018 issue.

Manifesto more than music seemed to hover over New York City’s music scene in 1976. On the one hand, modernists like Babbitt, Carter, Boulez and Charles Wuorinen cast their uncompromising shadow; on the other, local premieres of music by Steve Reich and Philip Glass edged minimalism closer to the mainstream. Rediscovered swing-era veterans like singer Alberta Hunter and stride pianist Joe Turner held forth in Greenwich Village, while soon-to-be-gentrified Soho provided a forum for avant-garde jazz and genre-bending experimental music. It was a dizzying time for us budding undergraduate music students torn in all directions; likewise for Europe-based American composer and pianist Frederic Rzewski, then living in New York (he returned to Europe in 1977, settling in Brussels). He briefly played with the Glass and Reich ensembles, yet you also could catch him giving heady recitals in small venues, with repertoire ranging from Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata, Eisler’s Third and Beethoven’s Hammerklavier to Tom Johnson’s An Hour For Piano.

I knew something about Rzewski’s formidable pianism from my well-worn LP of Stockhausen’s Klavierstück X. But my fellow musician classmate David Feingold turned me on to something even wilder, more atonal and more freewheeling than the free jazz occupying my attention: a recording by Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV), an acoustic–electronic improvising aggregation whose founder members included Rzewski, Richard Teitelbaum and Alvin Curran. He also brought over an LP with dayglo cover art containing Rzewski’s composition Coming Together (1972). Instead of MEV-like mayhem, this music abounded with gritty, chugging rhythms, along with obsessive repetitions of musical phrases and texts from a letter written by the convicted radical activist Sam Melville, a key figure and victim of the 1971 Attica Prison riots. It felt improvisatory, yet it clearly wasn’t improvised. Nor was it quite jazz, nor rock, nor classical. It seemed closer to Terry Riley’s In C in terms of style (maximal minimalism?), if not content.

None of this, however, prepared me for Ursula Oppens’s November 1976 New York premiere of Rzewski’s piano piece The People United Will Never Be Defeated! (1975). Following a defiant Chilean resistance tune, 36 virtuosic variations unfolded, alternating between brash romanticism, pointillist post-Webern explosions, jazzy reflections, pompous marches, modal musings and increasingly intensified allusions to the theme. It lasted about an hour. To my ‘expert’ 19-year-old ears, it felt like an eternity. How could Rzewski write something so pretentious and self-indulgent? I resolved never to hear it again. But I did – when Rzewski himself played it in upstate New York. This time it bowled me over. Its stylistic juxtapositions now sounded audacious and daring rather than contrived, unified by a tightly knit structure that I hadn’t noticed before. Before the theme’s final recapitulation, Rzewski improvised a long, dazzling cadenza. Suddenly the idea that one could be a classical pianist, a composer and an improviser all at the same time hit home, and I unwittingly landed a role model, who eventually become a mentor, a colleague and a friend.

Rzewski started playing the piano aged four, and was already trying to compose. His first music teacher, Charles Mackey, was a crucial influence. ‘When he saw that I was writing little pieces that fooled around with dissonances,’ Rzewski told me, ‘he said, “If you want to write this kind of music you should really listen to the people who are experts at it,” and turned me on to Schoenberg and Shostakovich. Mackey talked to me about Hegel and Schopenhauer and had strong leftist sympathies. He instilled in me the idea that music shouldn’t be just notes and sounds and numbers but have something to do with reality. Reality is both rational and irrational. The universe has a structure with elements that can be predicted, but there are things that have no structure and that cannot be predicted. I think it’s interesting to have pieces with an elaborate structure and, at the same time, a basically chaotic spin which goes nowhere and that may lead to unpredictable and even incoherent results. And I think this helps to make the music more like real life.’

Rzewski found this attitude severely lacking in his subsequent studies at Harvard and Princeton, and he gravitated instead towards fellow radicals like David Behrman and Christian Wolff (who introduced him to Cage and Tudor). Yet he does remain grateful for his early grounding in traditional counterpoint, and finds that many younger composers lack this skill.

Moving to Europe, Rzewski claims, helped him to stake out his identity. A Fulbright scholarship (1960) allowed him to study in Florence with Dallapiccola; at the same time, he established his reputation as a dynamic, incisive new-music pianist, collaborating with Gazzelloni, Maderna and Stockhausen, among others. When MEV was formed in Rome during the mid-1960s, the city was a hotbed of artistic innovation. This atmosphere lent itself to MEV’s organic fusion of improvisational and theatrical elements, and spilt over into Rzewski’s evolving compositional output. Aspects of what would later emerge as minimalism are present in Coming Together and Attica (both 1972), and also in the additive melodic formulas throughout Les moutons de Panurge (1969). In Jefferson (1970), composed following the 1970 Kent State massacre, Rzewski sets the opening of the Declaration of Independence in the fashion of an incantatory cantus firmus, where the metrically shifting piano writing makes a fascinating foil to the text’s sober, lofty sentiments.

Another crucial contact was Cardew, whose last piano works embraced 19th-century tonal idioms in order to depict social realism. Rzewski developed these ideas in No Place to Go but Around (1974), a short set of variations. In retrospect, its harmonic and pianistic characteristics seem to be a prototype of the longer The People United. Political and social issues similarly inform other piano variation sets such as Mayn Yingele (1988), as well as The Price of Oil (1980) for mixed ensemble, and two choral pieces, Stop the War! and Stop the Testing! (both 1995).The North American Ballads (1978-79) for piano are four fantasies based on traditional folk songs addressing social issues. Originally written for Paul Jacobs, they count among Rzewski’s most frequently performed piano works, particularly ‘Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues’. It begins with relentless, motoric rhythmic patterns in the piano’s deep bass. The patterns become forearm clusters of almost unbearable intensity, although moments of lyrical respite seep through the grim exterior.

Political overtones are less pronounced yet still present in Rzewski’s 1991 Piano Sonata, in which popular song and classical rigour engage in heated battle. Its central movement is a murky, haunting fantasy on the military bugle call Taps. By contrast, the first movement features six themes that no one in their right mind would juxtapose: L’homme armé, ‘Ring around the rosie’, ‘When Johnny comes marching home’, ‘Santa Claus is coming to town’, ‘Three blind mice’ and Lennon’s ‘Give peace a chance’. What’s more, the movement is partitioned into sections, each lasting half as long as the previous one, so that the tunes crush and compress, vainly struggling to breathe. L’homme armé returns in the third movement as the theme for a madcap set of variations. When I asked Rzewski why variation form so often features in his music, he said, ‘I don’t know, I guess it’s just a bad habit.’

Although Rzewski makes no great claims as an orchestral composer, his A Long Time Man (1979) for piano and orchestra and his Piano Concerto (commissioned for the BBC Proms, 2013) are inventive and skilfully wrought. His extensive chamber music output tends to embrace unconventional instrumental combinations and open scoring. For stylistic breadth and dramatic impact, his two-hour oratorio The Triumph of Death (1987-88; for string quartet plus any number of singers) may well be his theatrical masterpiece. It’s based on Peter Weiss’s play Die Ermittlung, encompassing harrowing testimony from both victims and perpetrators at the Nuremberg trials. Antigone-Legend, Rzewski’s 1982 setting of Brecht’s poem translated into English, also qualifies for oratorio status, covering terse, turbulent and technically demanding ground over 53 minutes, as piano and voice weave in and out, barely pausing for air.

By and large, the piano remains Rzewski’s primary creative focus, although he often incorporates sounds from household and novelty items, utilises the piano lid percussively, or asks the performer to gesticulate, vocalise or whistle. While Rzewski may not have invented the ‘speaking pianist’ genre, he has incorporated spoken text into solo piano works to powerful and original effect, notably in the 1992 De profundis, an abridged setting of Oscar Wilde’s letter to Lord Alfred Douglas from Reading Gaol. The full gamut of Rzewski’s keyboard aesthetic can be found in The Road (1995-2003), whose eight large sections divide into a total of 64 smaller ‘miles’. The sections grow longer as the music progresses, with the whole lasting around nine hours – or more, depending on tempos or whether one improvises or not (Rzewski often indicates places in his scores to insert an optional improvised cadenza). Michael Schell describes The Road as ‘a postmodern counterpart to Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage’, and Rzewski likens it to ‘a novel for piano’, in the sense that its structure alludes to the tradition of solo piano long-form literature like the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, or Bach’s Das wohltemperirte Clavier, to be played at home, in one’s own time. Yet one might say the same for Rzewski’s cycles of shorter pieces, such as the books of Ludes (1990-91), or his series of 56 Nanosonatas (2006-10), mainly written in tribute to family and friends.

At 80, Rzewski remains a protean pianist who continues to perform his own works with a sense of dynamism, concentration and personal projection from which aspiring Rzewski interpreters can learn. Yet he’s also happy that recent big works commissioned for younger pianists like Daan Vandewalle (Songs of Insurrection, 2016) and Igor Levit (Ages, 2017) are in safe hands. In essence, Rzewski is continuing to shape and revitalise the time-honoured composer-pianist tradition. Jed Distler (August 2018)

Igor Levit's Sony Classical recording of Rzewski's The People United Will Never Be Defeated! (coupled with Bach's Goldberg Variations and Beethoven's Diabelli Variations) was Gramophone's Recording of the Year in 2016, a recording that prompted David Fanning to write, in November 2015, that 'if a finer piano recording comes my way this year I shall be delighted, but frankly also astonished'.

Listen in lossless audio on Apple Music below