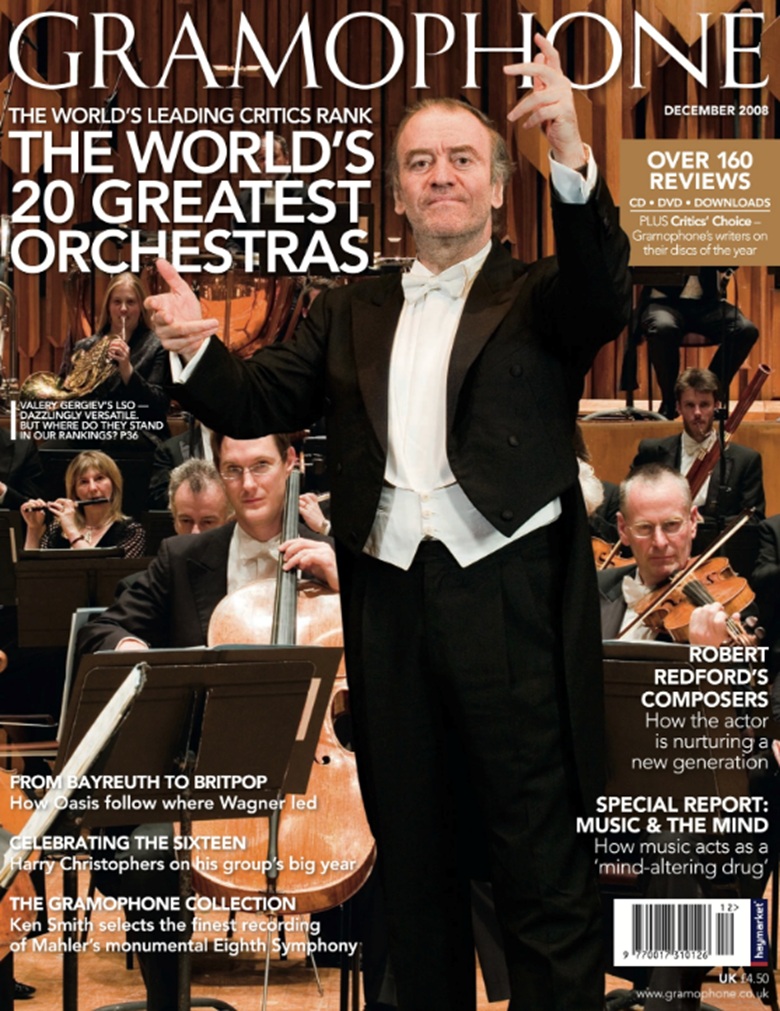

The World's Greatest Orchestras

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

The votes are in. Time to celebrate the best of the best. It’s a classical title showdown! Swapping gloves for glissandi and punches for prestos, players from around the globe square up for the hotly contested spot of World’s Best Symphony Orchestra

Ranking the heavy hitters is by no means an easy task, but Gramophone has manfully taken the job in hand. Our panel of leading music critics comprised: Rob Cowan, James Inverne, James Jolly (all from Gramophone, UK), Alex Ross (the New Yorker, US), Mark Swed (Los Angeles Times, US), Wilhelm Sinkovicz (Die Presse, Austria), Renaud Machart (Le Monde, France), Manuel Brug (Die Welt, Germany), Thiemo Wind (De Telegraaf, the Netherlands), Zhou Yingjuan (editor, Gramophone China) and Soyeon Nam (editor, Gramophone Korea).

To compare like with like, we have limited ourselves to comparing modern romantic orchestras rather than period bands, but apart from that distinction it’s a completely open field. The panel have considered the question from all angles – judging concert performances as well as recording output, contributions to local and national communities and the ability to maintain iconic status in an increasingly competitive contemporary climate.

The results have proven fascinating and will no doubt be as controversial as the question itself. But if nothing else, the task gives us all a chance to celebrate the forerunners of exciting, cutting-edge music-making. And that can’t be a bad thing…

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

The best of the rest…

We start our countdown from 20th to 11th place

20 Czech Philharmonic

Under current chief conductor Zdenek Mácal, one of the most characterful of orchestras has embarked upon recording projects that include the complete symphonies of Dvorák, Mahler, Tchaikovsky and Brahms. Eliahu Inbal is to take over as chief conductor from 2009.

19 Saito Kinen Orchestra

Formed by Seiji Ozawa in 1984 in honour of Hideo Saito (founder of the Toho Gakuen School of Music), this exciting orchestra is resident ensemble of the annual Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto in the Japanese Alps, and has made a number of acclaimed recordings for Philips and Sony.

18 Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

Since Peter Gelb took over as its general manager in 2006, the Met has rarely been out of the spotlight. But the roster of crowd-pleasing opera stars is apt to eclipse the great work done by the orchestra. Under James Levine, the players have toured in concert since 1991 and each year perform a subscription series at Carnegie Hall.

17 Leipzig Gewandhaus

Boasting a roster of former music directors including Felix Mendelssohn and Wilhelm Furtwängler, the Gewandhaus orchestra has been presided over by Riccardo Chailly since 2005, and under his leadership has released recordings of Mendelssohn, Brahms and Schumann symphonies. They carry their sense of heritage in everything they play.

16 St Petersburg Philharmonic

Russia’s oldest symphony orchestra celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2007. Under the direction of Yuri Temirkanov, who has been at the helm since 1988, this incredibly active orchestra toured Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China in October and November.

15 Russian National Orchestra

Since its founding in 1990 by music director Mikhail Pletnev, the orchestra has achieved considerable and consistent critical acclaim for its concerts and more than 60 recordings for DG and Pentatone. The RNO will launch its own annual festival in 2009.

14 Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra

Thanks to the vision of artistic director Valery Gergiev, the orchestra of the Mariinsky (formally Kirov) in St Petersburg has gone from strength to strength, with recordings on Philips covering much of the core Russian ballet and opera repertoire.

13 San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

Under the precise direction of Michael Tilson Thomas, the San Francisco Symphony has developed a beautifully polished, often theatrical sound. The orchestra’s own SFS Media label, launched in 2001, has thus far focused on a lauded Mahler symphony set and orchestral song-cycles.

12 New York Philharmonic

The USA’s oldest active orchestra is still going strong, and earlier this year, in an effort to form artistic ties with one of the world’s most politically isolated nations, made history by performing in Pyongyang, North Korea. Young and dynamic conductor Alan Gilbert should ensure the orchestra’s continued vibrancy when he takes over as music director in 2009.

11 Boston Symphony Orchestra

A classy and sophisticated orchestra, which each year provides the backbone for one of the world’s best summer festivals – Tanglewood. Its recording of Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs under current music director James Levine won the 2008 Grammy Award for Best Classical Vocal Recording.

10 Dresden Staatskapelle

This is one of the very few orchestras with its own distinctive sound. By which I mean a sound that is, perhaps more than with any other orchestra, immediately recognisable. This has to do with the orchestra’s heritage, somewhat with the fact that it was isolated during the Cold War, and also with the players’ awareness of this sound and their own wish to preserve it. And so the players pass on the knowledge of how to produce it to their pupils, who often succeed them in the orchestra.

I admit, my name is Nikolaj Znaider and I’m an addict. I’m addicted to this orchestra, and to the intoxicating, central European sound it creates today and that can be heard even on those old recordings under Wilhelm Furtwängler from the 1940s and ’50s. It’s an orchestral sound that almost no longer exists elsewhere. It’s hard to describe, because to do that one must become subjective, but I would aesthetically define it as a dark, wooden quality.

Less subjectively, the Dresden players play music the way I believe it should be played – with what is invariably called “a chamber-music quality”. That of course simply means actively listening to what goes on around you and relating what you do to that. With certain orchestras, definitely this one, you sense that every musician takes responsibility not just for their own part but for the music as a whole.

As I grow and develop, increasingly I have a need for that act of creating something that does not yet exist – something that must be brought into the physical world from the metaphysical. To do that it’s not enough to play my solo violin part; it is vital to play with a great conductor and a great orchestra, with people who have musical vision and share that need to express collectively something in the music.

So I play with the Staatskapelle whenever I can. Recently I have started sitting in the orchestra for a concert’s second half. Last year we played some dates in Dresden and each time after the interval I sat with them to play Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. To be in the midst of this group of people thinking and breathing as one, while still acting as individuals taking responsibility for their part in the whole, is the ideal. I can’t imagine any list of the world’s great orchestras without the Dresden Staatskapelle at or near the top.

Nikolaj Znaider

Violinist Nikolaj Znaider returns to conduct and play with the Staatskapelle in January 2009, for concerts marking Mendelssohn’s 200th anniversary

9 Budapest Festival Orchestra

For an orchestra that is only celebrating its 25th birthday this year, the BFO has risen to the top with extraordinary speed. But then it’s an extraordinary set-up – a group of superb musicians who play with a passion and commitment that beggars belief. The combination of Iván Fischer, the orchestra’s founder and music director ever since, and these fine players has elevated music-making to a level that astonishes and delights with equal measure. This is not an ensemble in which the players fall into an easy routine – they know that their reputation relies on their continuing to deliver at white heat at every performance. Watching the BFO rehearse or record is like glimpsing chamber-music-making on a big scale, each player deeply concerned about his or her contribution to the whole. And in Fischer they have not a dominant ego, but a facilitator of remarkable sensitivity.

James Jolly

James Jolly is editor-in-chief of Gramophone

8 Los Angeles Philharmonic

I tend to think of a great orchestra as either one that has such a distinctive sonic personality that it sets itself apart, or one that is defined as special by the repertoire it plays. With Los Angeles, it’s probably the latter that you think about. In his years at the helm, Esa-Pekka Salonen has vastly broadened the scope of what the orchestra plays. You are almost as likely to hear them play a work by Steven Stucky as one by Beethoven.

So by now the LA Philharmonic is famous for its excursions into contemporary music. That gives them the ability to handle the technical demands of the repertoire in an important way. It also means that they’re very open to new thoughts and ideas.

So each conductor coming to that orchestra can place his or her individual stamp on the music, as opposed to a default interpretation that the orchestra provides. If, for instance, you go to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic in a Brahms symphony, it’s more than likely that you’ll get the Vienna Philharmonic’s performance of that Brahms symphony. It’s not like that with LA.

Their new hall is also a vital factor in their success. You can’t be a truly great orchestra unless you have a hall that gives you an environment in which to be unique, either in the repertoire that you choose to play or through the kind of sound you create. That hall may not be to everyone’s taste, but in point of fact Disney Hall has given this orchestra a real chance to bloom. They can do things they couldn’t do before because they were limited in terms of stage space – and they can do new things sonically because the hall is much more conducive to a wider sonic palette.

I expect Gustavo Dudamel’s arrival as chief conductor to continue the good times, and his upbringing in Venezuela will help him. He’ll probably introduce concepts he’s grown up with, trying to make music ever more a part of the community. And he can help the orchestra make a connection with Los Angeles’ large Hispanic population, a new audience that maybe hasn’t yet been fully reached out to.

Leonard Slatkin

Leonard Slatkin was principal guest conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra between 2005 and 2007

7 Cleveland Orchestra

In refinement of tone, impeccable intonation, ensemble tautness and the sheer warmth of sound, the Cleveland Orchestra is the Concertgebouw and Vienna Philharmonic practically rolled into one. America’s so-called European orchestra, it was made great by George Szell, an Old World autocrat, in the years following Second World War. No American-born music director before or after Szell moved to Cleveland. Most of the major commissions these days come from overseas. At the moment, Cleveland is a better place to find out what Oliver Knussen, Matthias Pintscher or the young Austrian Johannes Maria Staud are up to than is New York.

But nothing, in fact, could be more American than Cleveland’s orchestra. That it remains one of the world’s best in an economically struggling Midwestern city is the American can-do spirit in operation. Franz Welser-Möst, who is in his fifth season as music director, has his detractors. They call for a return to 20th-century predictability. Welser-Möst, instead, is moving Cleveland into the 21st century through his questing interpretations and inventive programmes. Nearly every week brings something current or a novelty from the past to the elegant and intimate Severance Hall. Though an Austrian, Welser-Möst has demonstrated a restless curiosity about American music, including the maverick tradition in the west, which is mostly ignored east of the Mississippi.

Even Welser-Möst’s detractors usually admit that his orchestra continues regularly to produce its trademark sound that’s hard not to love. The orchestra tours extensively and plays several weeks a season in Miami, helping out in Florida’s orchestra-deficient capital. And Welser-Möst now has a contract running through to 2018, which allows him the luxury of making long-term plans, assuring a stability not to be found elsewhere in the orchestral world.

Mark Swed

Mark Swed is chief music critic for the LA Times

6 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

Here is an orchestra that is not only very brilliant – it doesn’t have any weaknesses at all. They are enormously spontaneous and emotional performers, playing every concert like it could be their last. They give everything, more than a hundred per cent.

But the orchestra has a secret to its success.

As a radio orchestra, all of its concerts are recorded. Therefore all the players are at once accustomed to the idea that they must be technically perfect and unfazed by the presence of microphones – so, with the playing quality almost a given, they also concentrate on interesting and involved interpretation. They are trained to do both, which yields enormous results. In addition, they play a lot of contemporary music. That keeps them sharp; their sight-reading, for instance, is phenomenal. For me, as a conductor, it’s like driving a Rolls Royce. The orchestra can cope with everything.

Mariss Jansons

Mariss Jansons is chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

5 Chicago Symphony Orchestra

I have been playing with the Chicago Symphony for such a long time that I feel like a member of the family. When I performed with them for the first time I was 26 years old and they couldn’t have been nicer – they are just adorable people. As a student I had often heard them at Carnegie Hall under Solti, so playing a Liszt concerto with him conducting was like a fantasy come true.

But I have to say that each time I play with them it’s special. Last year I did a Brahms concerto under Haitink, and that was amazing. I am still at the point where I have a kind of thrill when I get to go on stage with a great orchestra, and they are incredibly talented, a very exciting group of players. I don’t think I have ever heard more brilliant Strauss and Mahler than I have heard in Chicago.

As an orchestra they have this gleaming brass sound that I think they are justly famous for. Some people criticise them for failing to balance that incredible brilliance, but I believe they are an orchestra that responds to what you ask them to do. When Solti was conducting them, he encouraged that brilliant sound, whereas when I heard them under Barenboim they sounded like a fantastically rich and deep European orchestra, so I think they are capable of pretty much anything. Chicago, like all great orchestras, have a kind of pride in themselves, regardless of who is on the podium, and this is an important element in maintaining a high standard.

Emanuel Ax

Pianist Emanuel Ax will next play with the Chicago Symphony in April 2010

4 London Symphony Orchestra

The LSO stands out from all the orchestras I’ve worked with because of its totally unique work ethic. The players are always 'on', whether it’s 9am or 9pm, whether they’ve been working flat-out all week or whether they’ve just come back from their holiday. You start work and they’ll immediately light up in a way I’ve never experienced anywhere else.

The LSO style is well known – there’s snappiness and vitality, a precision and a drive, and they give their all, especially when it comes to volume. Where does it come from? Well, they certainly have extraordinary versatility: they can play anything! But there’s an attitude that goes with that – they have the same openness to every project that comes their way. They have the vocabulary to be true to every style of sound that’s required. They’re constantly adapting.

They also benefit from great management, people who share with the musicians a curiosity about new things, and don’t shy away from new challenges. And as the players are involved in many of the decision-making processes, they choose to work with people who share their philosophy. They’re scrappers too – they love putting things together and the range of music-making they tackle is colossal! You always get the sense that they’re there because they want to be – there’s never any sense of grind. And that contributes to the immediacy of the experience.

Marin Alsop

Marin Alsop regularly guest-conducts the LSO

3 Vienna Philharmonic

It must be admitted that the Vienna Philharmonic, for all its deserved fame, does not always sound like the best orchestra in the world. It plays too many concerts, for one thing, and too many of those are with conductors unable or unwilling to bring the best out of the players. Sometimes, as when Valery Gergiev comes to visit, they can even sound brutal, like a second-rate symphony band. Sometimes the playing sounds boring, as long as maestri such as Daniel Harding address the orchestra’s possibilities without any apparent artistic concept.

But – and it’s a very big but – when the right conductor is before those players, it is a different matter entirely. When cultivated and inspiring interpreters such as Christian Thielemann, Franz Welser-Möst or the fabulous Bertrand de Billy (in opera as well as in concert) work with a sense of its deep well of musicality, the Vienna Philharmonic can sound like no other orchestra.

As it benefits from its daily activities in the opera house, the orchestra is able to form the smoothest transitions, the finest modulations of sound. That makes it incomparable, at least from time to time – whenever it exercises its option to be so.

Wihelm Sinkovicz

Wilhelm Sinkovicz is the classical music critic for Die Presse

2 Berlin Philharmonic

Contrary to popular mythology, I don’t think there is any such thing as a recognisable orchestral sound. However, you can recognise an orchestra by its way of playing. I have surprised myself on a number of occasions, turning on the radio in the car or in the kitchen, hearing an orchestra mid-flight and immediately knowing that it’s us. It has to do with the priorities of the players – we Berlin Phil musicians play passionately and emotionally, throwing ourselves gung-ho into the music – and that is evident even across the airwaves.

I have been a member of the orchestra for 23 years under three music directors (Herbert von Karajan, Claudio Abbado and Simon Rattle), and during that time we have changed and developed. Indeed, it would be a sad case if we had failed to do so. I think any institution that wears its traditions proudly on its chest must necessarily be aware that tradition is a living process. A performing tradition is not to be mummified, like a fly in a piece of amber or an exhibit behind glass in a museum, but instead is something that lives. By definition, it must evolve and adapt.

One of the principal points we addressed when considering where to take the orchestra after Abbado was whether we wanted to move forward into the 21st century, or back into the past. Abbado had already done the pioneering work. When he took on the job after Karajan he was stepping into immensely big shoes, but he managed to achieve a pretty radical revolution, which influenced orchestras throughout the world. He would take a fairly traditional programme and present it in a certain way, causing the audience to sit up, take notice and really clean out their ears. And within a fairly short space of time other orchestras were attempting more daring programmes, too – as if they had simply been waiting for someone to take the lead. Now that we have Simon Rattle, we do perform a greater number of contemporary works. Many musicians around the world haven’t quite come to terms even with the 20th century yet, but Simon is a conductor for the 21st century.

As a musician, if I had been reduced to playing nothing but Brahms and Beethoven – magnificent works as they are – that would be a very thin diet. I have enjoyed the journey and adventure with this orchestra immensely because my musical education has benefited consistently year on year by pushing the envelope. It’s a tremendously rewarding and uplifting working environment – not the kind of high-pressure situation where you worry every day whether you will be good enough. I certainly don’t feel there is a Damoclean sword over my head, but it’s none the less a challenging environment. In meeting these challenges we orchestral musicians experience greater satisfaction and are able to raise the bar again – but it does require total commitment from every single player.

Fergus McWilliam

Fergus McWilliam is a horn player for the Berlin Philharmonic

1 Royal Concertgebouw

Of course I knew the Royal Concertgebouw from records long before I ever conducted them. I loved the early Mengelberg recordings and later those with Bernard Haitink. Standing on the podium before the musicians, I always appreciate just how special they are. Their approach to music-making goes far beyond questions of sound; it is so profound, so deep, so noble. They create with you a unique atmosphere, they make you feel that you have entered a very special world.

They have an understanding of each composer like an actor understands his roles – they interpret, and shift into the appropriate character. It comes from a hunger to comprehend what is behind the notes. Notes are after all only signs, and if you only follow the signs they won’t get you there. Yet very few orchestras in the world have that quality of knowing the depth and the character of the music. We have many technically good orchestras these days. But this musicial intelligence, allied to the orchestra’s very personal sound, makes the Concertgebouw stand out.

In rehearsals the players talk with you on a fascinating level about interpretation. So often rehearsals can be simply about organisation: you are expected to come in and say only, “Here a little louder, here a little softer,” which is all very primitive. The Concertgebouw players expect something extra from you, an interesting interpretation, illuminating ideas, a fantasy. If you offer them that, they play with a passion as though for a new piece rather than a work they have played a million times before. This is what the players want – that higher level, when you forget about the notes and play the image, the idea.

All the truly great orchestras boast an individual sound, which is far from the norm today. When I took over the Concertgebouw, journalists asked me what I would change. I said, “Nothing for the moment. It’s my task to find out their special qualities and preserve them. Then, if through a natural process my own individuality adds something – and theirs to me – that will be fine.” I would never set out to change the Concertgebouw. We continue to learn together.

Mariss Jansons

Mariss Jansons is chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw

Five out of five

Five great recent recordings to best experience Gramophone’s top five orchestras

Royal Concertgebouw Orch / Mariss Jansons

R Strauss An Alpine Symphony. Don Juan

RCO Live RCO08006 (A/08)

Elegant and beautifully controlled playing from the great Dutch ensemble: this is a journey that shows off Jansons’s unrivalled ear for orchestral colour

BPO / Simon Rattle

Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem

EMI 365393-2 (5/07)

A recording in great Berlin Brahms tradition – recognisably BPO, and also very Simon Rattle!

VPO / Georges Prêtre

“New Year’s Day Concert 2008”

Decca 478 0034

No orchestra plays this music like the VPO – and shows it such respect. This year Prêtre brought a little Gallic sheen as well

LSO / Valery Gergiev

Mahler Symphony No 6

LSO Live LSO0661 (6/08)

A staggering memento of the new LSO/Gergiev partnership and a vivid reminder of the orchestra that always gives 100 per cent

Chicago SO / Bernard Haitink

Shostakovich Symphony No 4

CSO Resound CSOR901 814 (11/08)

The great Chicago orchestra responds to Haitink with playing of frightening commitment and power

UP-AND-COMING

São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra

The orchestra performs more than 130 concerts each season, bringing to Brazil around 60 guest musicians of the calibre of Kurt Masur, Krzysztof Penderecki and Emmanuel Pahud. Directed by John Neschling since 1997, the orchestra has undergone something of a transformation in the last 10 years – under his leadership its subscription series and educational programmes have flourished, as has a fruitful recording partnership with BIS.

China Philharmonic Orchestra

In some ways, the China Philharmonic is something of a baby, in others, a wise old sage – it was established only in May 2000, but from the ashes of the old China Broadcasting Symphony Orchestra. Its artistic director, Long Yu, is one of the country’s foremost conductors and a very fine technician who arguably brought new standards of orchestral playing to China. As the country’s interest in classical music surges, so does the China Phil.

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic

When Vasily Petrenko became the orchestra’s principal conductor in 2006, he became the youngest person to hold the position in its 165-year history. With his appointment, an ensemble with a distinguished pedigree of principal conductors – including Sir Charles Hallé, Sir Henry Wood and Sir Malcolm Sargent – cemented its commitment to promoting classical music as a valid art form for contemporary audiences.

PAST GLORIES

NBC Symphony

A vehicle for Arturo Toscanini, the NBC radio network’s house orchestra was established in 1937 by recruiting prominent musicians from around the country. Its weekly concert broadcasts, which continued until 1954, were supplemented by tours of South America in 1940 and the USA in 1950. A comprehensive recorded legacy – on both CD and DVD – is available from RCA. Many of the orchestra’s musicians went on to form Symphony of the Air under Leopold Stokowski.

Philadelphia Orchestra

Stokowski also succeeded in propelling the Philadelphia Orchestra to international eminence as its principal conductor from 1912 to 1938. But it was under the orchestra’s next principal, Eugene Ormandy, that many of its most celebrated recordings were made. Ormandy remained as music director for 44 years, and in a diplomatic coup he conducted the orchestra in Beijing in 1973 – the first time an American orchestra had toured China.

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Under its founder Ernest Ansermet, this orchestra achieved special prominence for almost 50 years. After the Second World War it achieved particular acclaim through a long-term association with Decca, issuing a number of memorable recordings, including much 20th-century repertoire. During the 60s, in his final years at the orchestra’s helm, Ansermet concentrated on recording the symphonies of Beethoven and Brahms.