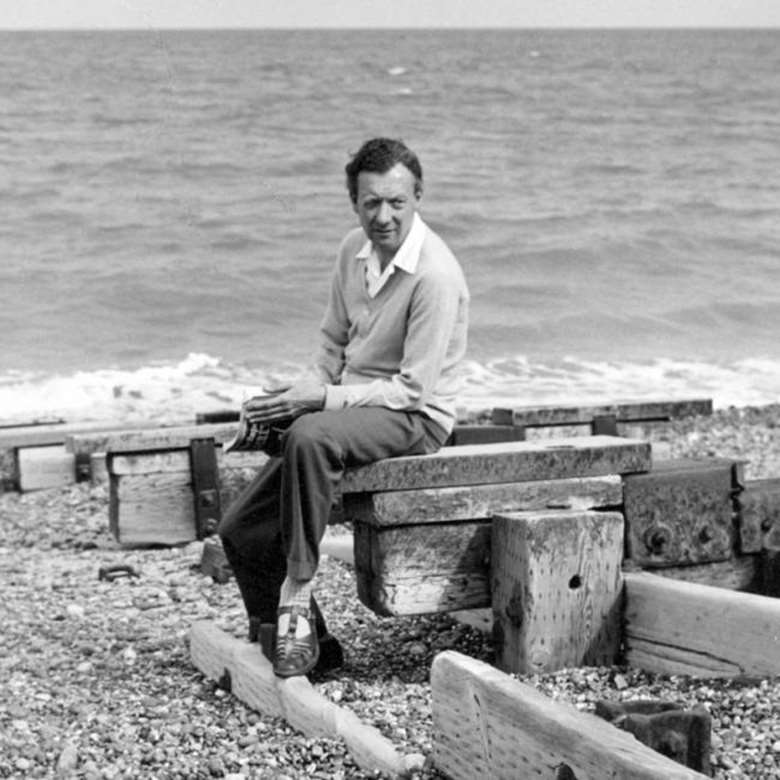

Ben: A tribute to Benjamin Britten by John Culshaw

James McCarthy

Friday, October 5, 2012

'Our job', he once said, 'is to be useful, and to the living'. And he was.

He was a consciously practical composer in that, so far as I can recall, he never wrote a note unless it was going to be useful to someone. He liked to write with specific people in mind, not just because of their professional skills but because of their qualities as human beings, and the names come leaping to mind: Peter Pears, Kathleen Ferrier, Joan Cross, Owen Brannigan, Janet Baker, Fischer-Dieskau, Rostropovich and a host of others. Owen Wingrave was cast before it was written, because he wanted to think about human beings rather than dramatic abstractions.

I am writing this in Adelaide, South Australia, on December 7, 1976, the day of his funeral in Aldeburgh, and it is hard to collate memories of the 25 years or so that we worked together in recording or television, partly because there are so many memories and partly because it is too soon to accept that, at 63, he is dead. The happiest hours I have spent in any studio were with Ben, for the basic reason that it did not seem that we were trying to make records or video tapes; we were just trying to make music.

His was a complex character, and superficially full of contradictions. He was world famous but he did not care for the trappings of fame. He was a marvellous pianist and conductor, yet he did not enjoy performing and the prospect of a concert sometimes made him literally sick. As he grew older, he seemed to harbour increasing doubts about his own works – doubts which were not shared by his colleagues or by the public: witness the triumph of Death in Venice at the Metropolitan, New York, in the autumn of 1975.

He could be very stern with an undisciplined orchestra or chorus. Professional musicians of the toughest order revered him all the same, and after a difficult session would retire to the nearest pub and drown their misbehaviour in pint after pint, while speaking in awe of his professionalism. He was a gentle person, and loved gentle pictures like those painted by his neighbour Mary Potter. But then he also loved fast cars, and before his illness he would drive brilliantly through Suffolk lanes narrow and twisty enough to frighten a cyclist, let alone his passengers, although there was no need for fear because he knew every tree and every curve and every place where a stray cow might be lurking; and he knew his stopping distance.

When he found out that I held a private pilot's licence he hired a Cessna for a Sunday morning joyride up and down the Suffolk coast, a prospect which didn't seem to frighten him or Peter Pears one little bit, although I drew comfort from the fact that the fourth party on board was also qualified to fly. That was around the period when he was composing Curlew River, a period of change and introspection maybe, but not a time to cut himself off from the world of reality. In life and in music he was a realist.

I have never understood those who, in later years, accused him of musical conservatism. On the contrary, it seems to me that his whole career was a quest for something new – not just for the sake of 'newness', but because he hated to take the easy way and repeat himself. True, there is a connection between Les illuminations and the Serenade and the Nocturne; the song cycles with piano also establish a sort of pattern; but what of the decision to turn, after the triumph of Peter Grimes, to the intimate world of chamber opera? There were, I know, purely practical reasons for doing so; but for Ben Britten a practical reason was always a very sound reason. I am not writing about opportunism, but about vision. The chamber operas presented a fresh challenge, as did the eventual return to full-scale opera. His ballet, The Prince of the Pagodas, was another kind of challenge; so was the War Requiem and the church parables and all those marvellous cello works inspired by Rostropovich. I could not bear, on this of all days, to attempt an assessment of his music; all I can do is set down some memories in no special order. The assessment is for posterity to make.

There are several ways of driving back from Aldeburgh to London, but whenever I drove him to the city we took a scenic route which he had worked out in order to pass through some of the most exquisite parts of Suffolk and Essex, thus enabling us to hit the sprawl of north London as late and as deviously as possible. If we left The Red House in Aldeburgh shortly after nine in the morning we would arrive at the last genuinely country pub in time for a Bloody Mary around noon and still reach his London home for lunch. He did not like London; I don't think he liked any modern cities. He was only really at peace in Aldeburgh (and, perhaps, some years ago in Bali, although I am glad he did not return to see what has happened to Bali in recent times).

The Red House really was peace: a large, rambling place secluded from the town, to which various extentions and conversions had been added over the years. To be a weekend guest there was to relax completely; although, before his illness, Ben's own ideas about relaxation might not totally coincide with those of a city-dweller. Of course nothing was obligatory, and I enjoyed the long country walks, not least because he was an expert ornithologist, whereas I cannot tell a curlew from a duck; but I confess that more often than not I dodged the early morning swim before breakfast because, as a city-dweller, I had been awakened hours earlier by the dawn chorus of birds which those who live regularly in the country never seem to hear. By the time the birds had shut up I would be fast asleep again, and Ben and Peter would be in the pool or walking the dogs in the garden or at breakfast.

One of the cruelest ironies of Ben's early death is that he had kept himself so fit. He was no kind of health fanatic, but until the final illness he enjoyed the outdoor life: he walked regularly, he swam, he played tennis. He did not smoke, but he enjoyed a drink if there was conversation to go with it. He loved good food, and the best food of all was at The Red House because it was fresh, like fish straight out of the sea with vegetables from the garden.

The last time we had a meal together at The Red House, which was when there seemed to be at least a chance that his condition might not get any worse, we had grilled sprats which, he remarked, "really are worth the awful smell they make in the kitchen". Maybe it seems trivial to mention such things, but I don't think so, because they show the other side of a shy public figure. However well-read, however sensitive, however concerned about the state of music and indeed the state of man, he was at heart, like Elgar with whose music he eventually came to terms, a countryman. A deceptive simplicity, an earthiness, lies behind all his music, just as it lies behind the music of his beloved Schubert.

He was a reluctant performer both in public and in the studio, and yet he never lost command of his forces. In concert performances of the War Requiem he chose to conduct the chamber ensemble and thus relinquish overall control to another conductor; but in the recording he conducted everything, and I have still to hear a better performance. It was made in January 1963 in Kingsway Hall and because of the importance of the occasion, and without Ben's knowledge, my colleagues at Decca 'wired' the hall and the control room in such a way that we were able to record every word of the rehearsals and the comments during playback in the control room. Had we told Britten what we were up to he would, at worst, have refused to proceed or, at best, have become inhibited by the lurking, cunningly hidden, additional microphones. But there was a friendly purpose in this exercise, for over the coming months the hours and hours of rehearsal tapes were reduced to just under one hour; a major security clamp was placed on both the extracted and residual material, and eventually one record was produced bearing a properly printed Decca label with the serial number BB 50. It was then packed in an embossed leather sleeve and presented to Britten for his 50th birthday – November 22nd, 1963 – by Sir Edward Lewis. When we left the office Ben said to me, with a mischievous grin, "I shan't forgive you quickly for this!" But he did.

Apart from anything else, the War Requiem rehearsals revealed all over again his amazing ability to control and communicate with children. He loved writing for children, and he loved working with them. He always wanted them to understand just what they were doing, and just what the music was meant to convey. When it came to boys' voices, he preferred a rougher quality than the 'pure' sound of the cathedral choirs, which in his view put the emphasis in the wrong place. It was a view that he applied generally. "Frankly", he once said to me when we were discussing a casting problem, "I'm not very interested in beautiful voices as such. I'm interested in the person behind the voice". In other words, a beautiful voice controlled by a mind was a blessing indeed; on the other hand, a mindless beautiful voice was of no interest to him at all. The same, of course, went for instrumentalists and, not unexpectedly, other composers, although in the last 15 years or so of his life his tastes broadened, and sometimes in unexpected directions.

I don't think he ever came round to Wagner, though many years ago when he was going to India he told me he was taking a score to study (I think it was Götterdämmerung, but I'm not sure about that). At one stage he was invited to conduct at Bayreuth, but declined for obvious reasons (if he was going to conduct Wagner anywhere for the first time, Bayreuth would be the last place). His love for Purcell, Bach,Mozart and Schubert was evident whenever he conducted or played a note of their music.

He didn't care for the florid school of Italian opera, which he wickedly lampooned in A Midsummer Night's Dream, but he was passionate about mature Verdi. He was, I think, unsure about Tchaikovsky as a symphonist, but he loved the ballet music – indeed, The Prince of the Pagodas is more than an oblique tribute to Tchaikovsky. Then there were the personal enthusiasms: the music of Frank Bridge, and not just because Bridge had been Britten's teacher, and of Percy Grainger, because Grainger's music had a simplicity or – to use the same word again – an earthiness which spoke to him directly. Elgar did not appeal to him until late in life, and it would have been unimaginable in the 1950s to suggest that one day he would record The Dream of Gerontius and the Introduction and Allegro.

He had his share of disappointments, and the worst of them was the criticial butchery of Gloriana in 1953. In retrospect, the notices read like an act of spite, as if the critics had decided that he had had it too good for too long; 13 years later, at the time of the Sadler's Wells revival in 1966, most of them had changed their minds and were doubtless hoping that the public's memory was short enough to forget the bitter words of 1953. To that extent they were lucky: the public's memory is short, and in any case by 1966 the larger part of a new generation was ready to appreciate Gloriana. It still remains the single major work by Britten not to have been recorded, although it presents no casting problems. Perhaps Decca will make amends in this year of the Queen's Jubilee; and if it is recorded, it should be recorded in The Maltings.

It was in the summer of 1965 that Ben and Peter invited me to go and explore an old building at Snape which might, by a considerable stretch of the imagination and a lot of money, be converted into the kind of multi-purpose hall that was so urgently needed by the Aldeburgh Festival. We walked round The Maltings and then clambered inside. It was all but impossible to imagine what it would be like when gutted, because at that stage it consisted of floor upon floor with no through sight-line. We kept on descending until we reached the ovens in the basement. And yet...there was a feeling about the place, about its setting by the river with the view of Iken Church through the reeds and across the marshes, that made it right. If Ben was to have a concert hall on his doorstep, this was it; and in 1967, thanks to a superb conversion job by Ove Arup and Partners who joined in close acoustical collaboration with Decca and the BBC, The Maltings at Snape was opened by the Queen. Two years later it burned down to a cinder, yet in 1970 it was open again and, if anything, better than ever.

The Maltings is Ben's monument, although I am not sure he would have liked me to put it that way. It is not a monument in the sense of Bayreuth, because it was not built to serve the music of one composer: it was built to serve all music. It has proved to be a marvellous concert and recital hall; it can accommodate opera without strain; the many Decca recordings made there prove its quality as a recording location, and on at least three occasions – Peter Grimes, Winterreise and Owen Wingrave – the BBC turned it quite literally into a television studio. But, most important of all, its existence encouraged Britten to make many recordings which might otherwise not have been made at all, since they would have involved him in prolonged trips to London. At The Maltings he could work in peace, and in the environment that inspired so much of his work; the warmth and welcome of the building were, and will remain, a reflection of the man.

The first of his music that I ever heard was the Serenade for tenor, horn and strings. I was a serviceman at the time; it was towards the end of the war; and it was the original Decca recording. No other piece of contemporary music had, at that age, spoken so directly to me or meant so much. I had no reason to suppose that within five or six years I would be working with Ben and Peter in Decca's No 1 studio in West Hampstead, and that it would be the start of a long relationship which was to involve a lot of hard work, but which was also not without fun.

There was one evening when, after two Lieder sessions, they tried to remember a couple of cabaret numbers Ben had written years earlier to words by WH Auden, but both the words and the music eventually ran out. Then, in those days, there was the seemingly impossible problem of making David Hemmings in The Little Sweep sound as if he were up a chimney; the solution was to get him to sing into a globe rather like a goldfish bowl of which there was only one, and which he promptly dropped. (I think he was the only child-in-the-studio I have ever known not to be totally under Britten's control; but then, at that stage, who was to know he would turn into a film star?) Yet I must not dwell on frivolities, for although Ben had a strong sense of humour he loathed practical jokes. Despite the doubts he may have had from time to time about the media, he was strictly professional in any studio.

I believe his doubts have been exaggerated or at least misinterpreted on the basis of a speech he made at Aspen, Colorado in the 1960s. Nobody who actually disapproved of recording could have made as many records, and with such enthusiasm, as he did; but he sounded a warning with which few, I imagine, would disagree. Nothing in musical performance is ultimately definitive, and to that extent a recording is only representative of the artist's approach at the time of recording. There is evidence of this in his own work. His approach to Peter Grimes when he conducted it for the BBC television production in 1969 was quite different from that of the Decca recording, made 10 years earlier. His playing of Winterreise darkened and deepened over the years, magnificent though it was from the start. He could never be stale or complacent.

I saw him for the last time during the 1976 Aldeburgh Festival. He was very frail, but he made a massive and perhaps damaging attempt to attend as many events as possible. It was the right thing for him to do, whatever the risk, because it was not in him to admit defeat. (When we recorded Billy Budd in 1967 he, as the saying goes, 'put his back out' just before the last two sessions. Despite therapy and a special chair, I knew he was in agony throughout that day, but he was determined to conduct and thus finish the work, and he did.)

I am glad that he was present in The Maltings last summer to witness the triumph of his last work, Phaedra, and I think he knew that it was not a sentimental triumph. The audience may have marvelled about how, under such adversity, he could have written such a piece, and it was indeed an emotional moment when he rose to acknowledge the applause; but finally it was the music they were applauding because it had communicated: and for Ben, communication was what music was all about.

He would not wish me to end on a sentimental note, and I shall not. It is enough to say that we have lost, too soon, a great composer, an all-round musician, a professional; but it is also time to say that, in spite of his own modest remark, his music always has been, and I believe always will be, a great deal more than merely useful.