Icon: Julius Katchen

Jed Distler

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Jed Distler pays tribute to the American pianist who was renowned for his assured, big pianism and his daring recordings of Brahms – but who tragically died aged 42

Born in Long Branch, New Jersey, on August 15, 1926, Julius Katchen was an outlier among the outstanding American pianists to emerge on the international scene after the Second World War. In many respects, his full-bodied pianism contrasted with the more literally orientated, anti-sensual approach generally favoured by his contemporaries. At the same time, his erudition extended beyond music, from his youthful studies in philosophy and English literature to his avid and canny pursuit of fine Japanese netsuke.

Pianist Earl Wild defined ‘big piano playing’ as the ability to let go in performance and to not worry about making the precise ritardando or crescendo – to play the music in a grand style that is not hampered by anything pedantic. You hear this time and again throughout Katchen’s discography. His Schubert Wanderer Fantasy is one of the most robust on record, and anything but square. Listen, too, for the exuberant temperament, surreal rubatos, demented inner voices and caffeine-fuelled fast movements throughout his Schumann Carnaval. By contrast, his Chopin Polonaise in A flat matches Rubinstein’s, Horowitz’s and Lhévinne’s for sheer ardency and swagger.

Perhaps Katchen’s confident and assured demeanour resulted from having worked with such an exacting and demanding a taskmaster as David Saperton, whose students also included Bolet, Cherkassky and Abbey Simon. As such, Katchen acquired an all-encompassing technique that knew no difficulties (Balakirev’s Islamey and the notorious octave passages in Liszt’s B minor Sonata were child’s play for him), abetted by a colourful and penetrating sonority that was always clearly projected, no matter how large or unwieldy the venue. A concert-hall ambience and judicious soloist–orchestra balance especially enhances the vivid impact of the pianist’s swashbuckling 1958 studio recording of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 2, which is further graced by Sir Georg Solti’s scintillatingly contoured orchestral framework.

Katchen’s big pianism extended to his programme concepts. He relished marathon evenings and multiconcert cycles that harkened back to the respective heydays of Busoni, Petri and Arrau, and to what Richter and Rubinstein would have served up at New York’s Carnegie Hall. Katchen thought nothing of presenting three demanding concertos in a single programme at London’s Royal Festival Hall, or of offering the entire Beethoven Appassionata as an encore following a programme given over to that composer’s Diabelli Variations and Schubert’s epic Sonata in B flat, D960.

Yet among these epic undertakings, Katchen’s traversal of Brahms’s complete solo piano works in four lengthy London recitals may have been the most meaningful and fulfilling. He nearly always managed to reconcile this composer’s intellectual and structural rigour with the music’s underlying lyrical impulses and sometimes underrated pockets of humour. In Brahms, Katchen’s propensity for daring was a double-edged sword, as cogently borne out in Concerto No 2 in B flat. His muted restraint in the slow movement’s long chains of trills defines the untranslatable Spanish word duende. Conversely, in the finale, at the coda’s outset, listen to Katchen start the right-hand octaves at a deliberate trot, while he slyly speeds up to a devilish sprint towards the finish. It’s not what Brahms wrote, yet it works, and one could imagine the composer winking in approval.

Nor was Katchen averse to the occasional crossover dalliance, although he was anything but a populist on the scale of Van Cliburn or Lang Lang. His debonair solo work in Gershwin’s Piano Concerto and Rhapsody in Blue distances itself from easy-listening luminary Mantovani’s oleaginous orchestral backing. And while his affinity with Classical repertoire seemed to be more acquired than innate (I jokingly refer to his overly facile Beethoven Op 120 as the ‘Oscar Peterson Diabelli Variations’), he fervently if selectively embraced 20th-century fare; Britten specifically requested him for his recording of the Diversions for piano left hand and orchestra. Katchen first recorded Bartók’s Third Concerto when the work was relatively new (eight years old), and collaborated dazzlingly in Stravinsky’s Petrushka with Monteux, who famously led its 1911 premiere. The pianist’s vivacious and crisp Prokofiev Third from his last recording session belies any notion of terminal illness (he was to die from cancer in April 1969). I once wrote in a comparative review that in the Prokofiev, ‘The Argerich version smokes. But Katchen’s inhales!’

Katchen made the pioneering and still unsurpassed recording of Ned Rorem’s Second Piano Sonata. The composer admired the interpretation as well as his friend’s prodigious capacity for both work and play: ‘I remember him going on tour without his music,’ recalled Rorem. ‘But not because it was all photographed in his brain: it was photographed in his fingers.’

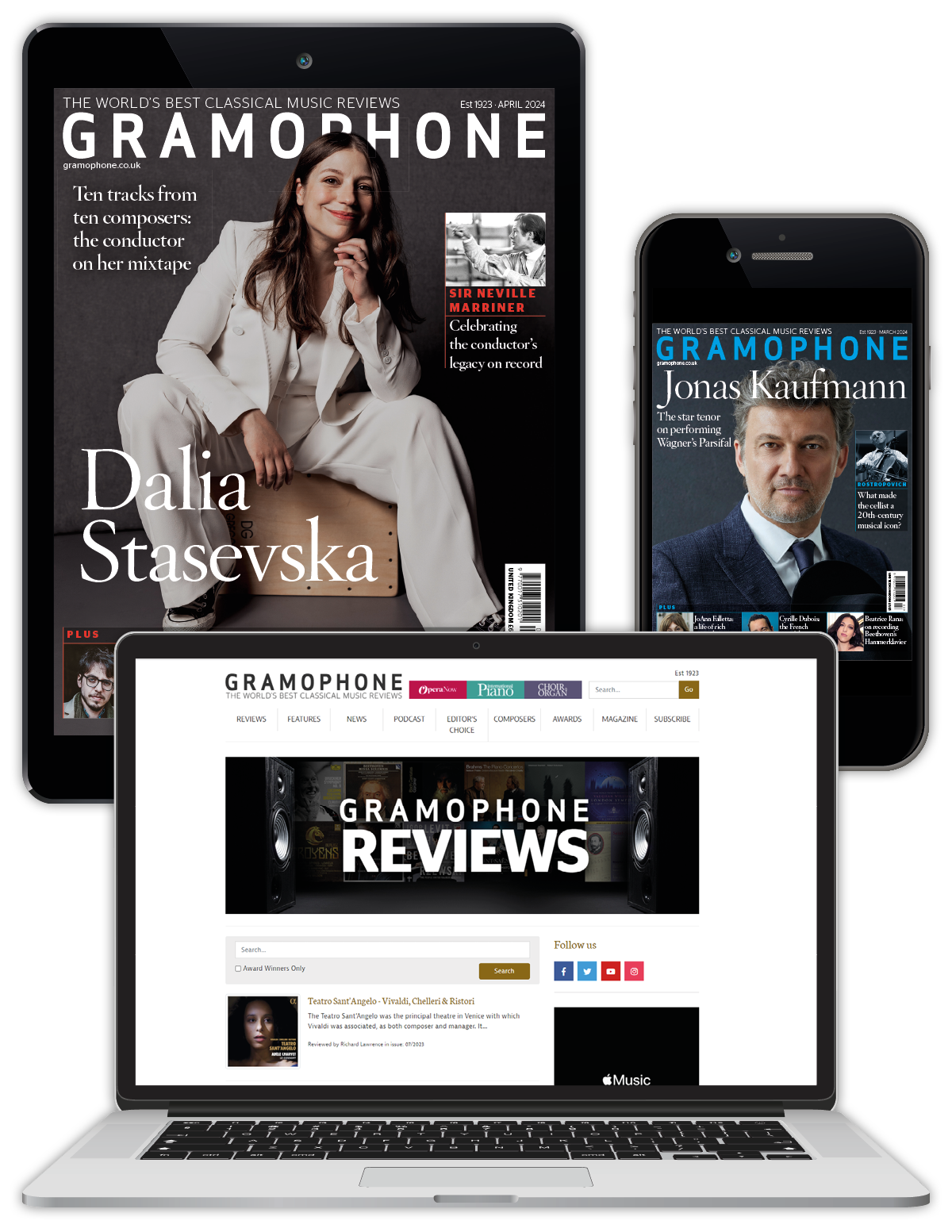

This article originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

Defining moments

1937 – Early concerts

On October 21, the 11-year-old Katchen plays Mozart’s D minor Concerto with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. He repeats the piece on November 22 with Sir John Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, New York, earning critical praise.

1946 – Formative years

Katchen graduates first in his class from Haverford College, and is awarded a fellowship by the French government for his academic achievement. He signs an exclusive contract with Decca, and represents the United States at the first international Unesco festival, followed by extensive touring. For professional reasons, Katchen adopts Paris as his permanent home base.

1949 – First long-playing disc

With the changeover from 78rpm discs to long-playing technology under way, Katchen’s recording of Brahms’s Sonata No 3 in F minor, Op 5, is released as Decca’s first solo piano LP.

1962 – Outspokenness

While on tour in East Germany, Katchen publicly condemns the Berlin Wall. Russian officials declare his comments defamatory, and forbid Aram Khachaturian from recording his Piano Concerto with him as soloist at a scheduled session with the Vienna Philharmonic.

1964 – Brahms cycle in London

Between April 12 and 22, Katchen surveys Brahms’s complete works for piano solo over the course of four recitals at Wigmore Hall.

1968 – Rock and Roll Circus

On December 11, Katchen is recorded to appear on a TV special The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. He is to die a few months later, on April 29, and although the programme is not aired at the scheduled time, it is released in complete form on DVD in 2004.

2005-06 – Posthumous netsuke sale

Sotheby’s sells pieces from the Julius and Arlette Katchen netsuke collection at auction for a huge sum. Further pieces fetch another significant sum a decade later at Bonhams.