'More!' The surprising history of the encore

Jeremy Nicholas

Monday, January 12, 2015

Jeremy Nicholas explores the history of the encore and why there is a fine line between delighting the audience and boring them to tears

The formal programme is complete, the audience is on its feet clapping and cheering and, after the second or third return to the platform to acknowledge the applause, our soloist indicates that he or she is going to play something more. A brief pantomime follows: an encore? Really? Me? Are you sure? Oh, very well then. After this display of faux modesty, there is that delicious moment when everyone quickly resumes their seat and utter silence instantly returns to the hall. There may be a muffled announcement from the artist of the encore’s title and composer. Neighbours look at each other. Did you catch that? Was it Lyapunov or Lyadov? (It’s bad form, by the way, to identify the title of the encore to your baffled neighbour until the piece has been played. ‘Lyadov, Etude, Opus 37, F major’, you whisper - not too loud, just enough so that the people behind can hear you as well. Try not to sound too smug.)

The artist then launches into what he or she secretly hopes will be the first of a string of carefully selected bonbons. The average is about three. Evgeny Kissin played seven at the end of his historic solo recital at the Proms in 1997. That is very good going. Michael Ponti offered nine at the end of his 1972 New York debut. The audience wouldn’t let him go. The 11-year-old Saint-Saëns would offer any one of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory.

Pianists have one advantage over orchestras and fellow instrumentalists: their encores come as a complete surprise. The element of spontaneity is somewhat compromised by the sight of a score on the conductor’s podium or accompanist’s music desk waiting to be played. By ‘encore’ nowadays we invariably mean a short and often ostentatiously difficult piece offered by the artist as a kind of bonus. The best ones dazzle, beguile, intrigue, charm or amuse. ‘Encore’ is a French word with a variety of meanings (still, longer, yet, again, etc). The one thing it doesn’t mean is ‘Please play some more’. When the French and Germans ask for an encore they say ‘Bis’ (‘twice’) just as the Italians do – paradoxically, for though ‘encore’ is French, the word’s entry into the English language was by corruption of the Italian ‘ancora’ (‘again’), used from the early 18th century onwards by audiences of the Italian Opera in London.

This other and earlier definition of ‘encore’ in its musical sense (i.e. the repetition of a piece that has just been performed) is experienced less frequently these days. It too relies on the vociferous demand of the audience for it to happen but it was a practice that, in this case, came to be viewed as a thorough nuisance. The progress of a new symphony could be interrupted by the audience’s insistence on a particular movement being encored. For the first performance of The Creation, Haydn printed a request stating that while he was always flattered by the approbation of the public, if the audience was kind enough to approve of his new work would it kindly show its appreciation by not asking for encores so as not to interrupt the work’s continuity.

It was a common occurrence for a programme to be halted by raucous requests for a ‘repetition encore’. We read of the great English tenor Sims Reeves in 1875 at a ballad concert singing ‘Tom Bowling’. He returned to the stage five times to acknowledge the applause and cries of ‘Encore!’ but was blowed if he was going to sing the song again. ‘[The audience] was not to be thus baulked. They refused to listen to Miss Brousil, who attempted to play a violin solo; they hissed and hooted Mr Pyatt, who, after endeavouring to obtain a hearing, led Miss Brousil from the platform.’ At any other event, opined the writer, ‘any person preventing an entertainment from proceeding by persistent noisy demonstration would be forcibly ejected by the police’. The phenomenon of the unwanted encore got so out of hand that in the 19th century, at some of the great choral festivals, it was the custom for some exalted individual, usually the bishop, the dean or the mayor, to decide whether an encore should be given and which it should be.

As late as the 1930s, some opera houses had to endure singers halting the dramatic action while they responded with encore after encore that had nothing to do with the opera. Jan Kiepura, the Polish tenor, always ensured there was a piano in the wings ready to accompany his encores. D’Oyly Carte performances of Gilbert and Sullivan had a tradition of automatic repetition encores until Rupert D’Oyly Carte decided to curtail them. ‘The performances tended to go on for ever,’ recalled conductor Isidore Godfrey. ‘A couple of handclaps and the artists would be away again.’ Many concert halls took to printing ‘No Encores’ in programmes or even displaying huge placards with the same prohibition.

Orchestral encores are in short supply nowadays. Union regulations and the threat of overtime have helped eliminate the practice. And not enough conductors like to spend time on fluff. Farewell the Beecham ‘lollipop’, though The Blue Danube and Radetzky March are encored de rigeur at the Vienna New Year’s Day concert. An encore of a new short orchestral work, on the other hand, is a badge of honour, such as the premiere of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No 1 which had to be given a double encore at its 1901 Proms premiere. Yet when it comes to instrumental soloists playing encores after a concerto, orchestral players hate them according to Fritz Spiegel: ‘Mutterings like “Haven’t they got homes to go to?” are soon heard. Notice also, when encores are played, the contrast between the triumphant and grateful smiles on the face of the conductor and the patiently bored looks of the orchestra.’

Occasionally, when a recital ends with some lengthy and/or profound musical utterance, an encore (jaunty or otherwise) is deemed inappropriate. Or an artist might be simply too exhausted (or jet-lagged) after a lengthy, stamina-sapping programme. Dinner. Drink. Bed.

One unusual reason for accepting an encore was given by the eccentric Vladimir de Pachmann at a June 1896 concert. After a particular piece was wildly applauded, the pianist turned on the audience: ‘No, no! You know nothing about it. I played the piece very badly, and will play it again.’ And then there are those artists whose musical credo precludes playing anything extra at all. ‘Applause is a receipt, not a bill,’ said one of them, Artur Schnabel. The stage is left bare and the audience shuffles out feeling slightly short-changed.

While there are few soloists who do not acknowledge an effusive reception with a musical thank-you, there is a small number who cultivate the art of the encore. For some in the audience, that section of the concert becomes an important enticement for going to it in the first place. Vladimir Horowitz would drive audiences wild with his transcriptions of The Stars and Stripes Forever, Carmen Variations or Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 2. Shura Cherkassky’s specialities were Shostakovich’s Polka from The Age of Gold, Morton Gould’s Boogie Woogie Etude and his own Prélude pathétique. At Josef Hofmann concerts, the audience would actually shout out the titles they wanted to hear: Rubinstein’s Melody in F, Moszkowski’s Caprice espagnol, the Schubert/Tausig Marche militaire and Mendelssohn’s Spring Song among many more. Hofmann’s post-recital ritual could be lengthy as pianist-composer Abram Chasins reported: ‘His beloved warhorses inflamed the fans to an insatiable and hysterical pitch.’ Hofmann’s great friend Leopold Godowsky was in the audience one night with his wife. ‘Mrs Godowsky started to leave. “Aren’t you going?” she asked her husband, who gave no sign of rising from his seat. “I’m not budging,” answered the mischievous Godowsky, “until Josef plays The Rosary!”’ Another Hofmann favourite was Rachmaninov’s Prelude in C sharp minor. Rachmaninov himself was rarely allowed to leave the stage before playing ‘It’, as he called the piece he grew to loathe – as well he might: he had composed the Prelude when he was a young man and sold the copyright outright to his publishers for a handful of roubles.

Of course, you must be sure that the audience really do want more. There’s the old story of the English tenor making his Lieder debut in Vienna. After the first number there were vociferous cries of ‘Bis!’ He duly obliged by repeating the song. Again, its end was met with a hail of ‘Bis! Bis! Bis!’. The tenor smiled, put his hand on his heart and bowed deeply. He sang the song for a third time – with the same result. How gratifying, thought the tenor, to be so enthusiastically greeted by these sophisticated, music-loving Austrians. ‘Meine Damen und Herren,’ he said, ‘thank you so much but may

I be permitted to continue with my recital?’ ‘Nein!’ came a voice. ‘Not until you sing the first one properly!’

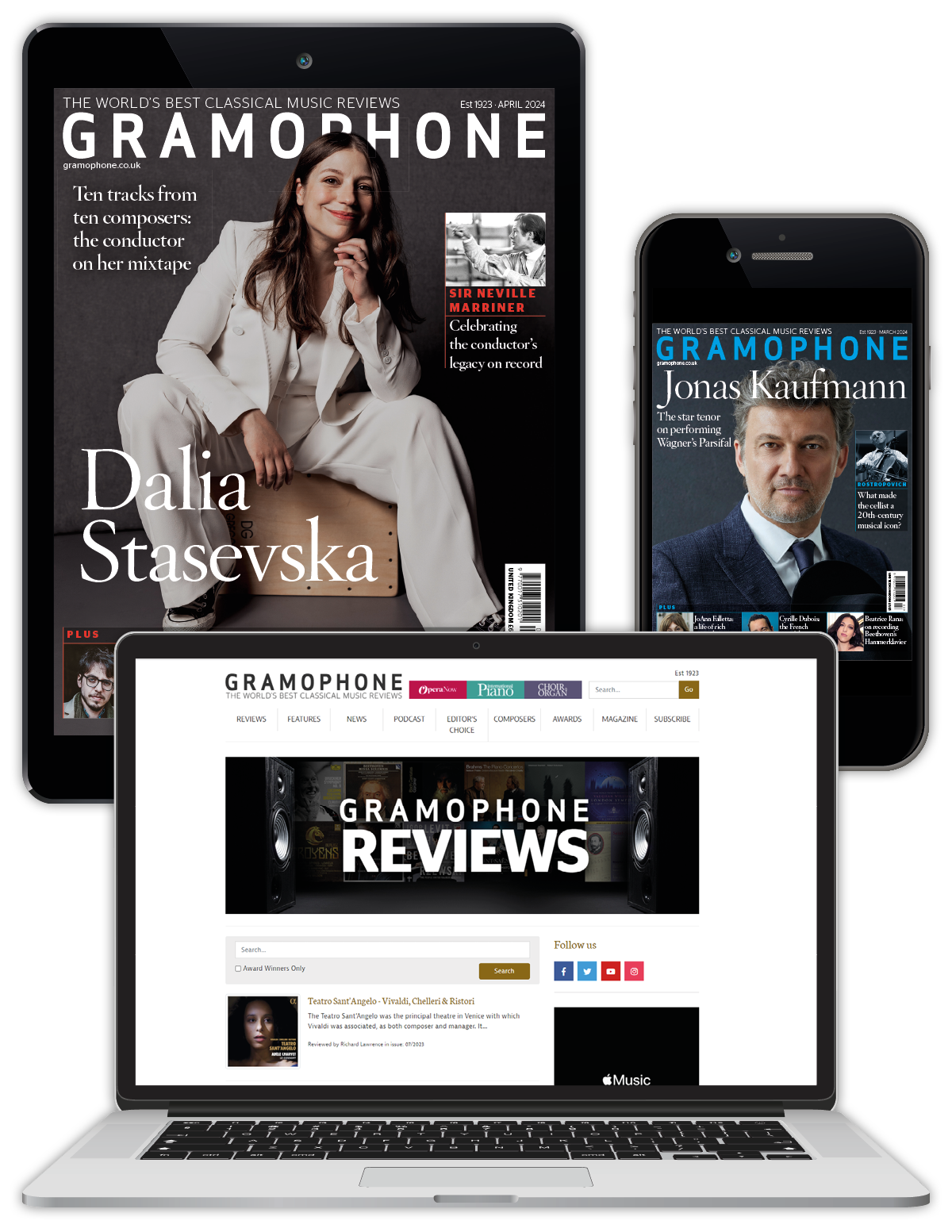

This article originally appeared in the March 2014 issue of Gramophone.