Mozart's Don Giovanni: a guide to essential recordings

Richard Lawrence

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

No single production can handle all the facets of this fascinating opera, so imagination must come into play. Richard Lawrence selects the best recordings

Mozart’s letter of January 15, 1787, to his pupil and friend Gottfried von Jacquin is well known, but still worth quoting: ‘Here they talk about nothing but Figaro. Nothing is played, sung or whistled but Figaro. No opera is drawing like Figaro. Nothing, nothing but Figaro.’ Le nozze di Figaro had been premiered in Vienna on May 1, 1786, but it was the production in Prague later that year, mounted by Pasquale Bondini’s Italian opera company, that was the greater success. Mozart and his wife travelled there in January 1787, and it was from Prague that the composer wrote to Jacquin. By the time he and Constanze left for Vienna on February 8 he had secured a commission to write a new opera for Bondini.

That opera was Don Giovanni, with Lorenzo da Ponte again providing the libretto. It was to be a busy year for both men; moreover, Mozart had to deal with the emotional shock of his father’s death in May. The Mozarts returned to Prague in early October 1787 with some of the music still to be composed. Mozart knew all but one of the singers and, as usual, he tailored his music to their voices. He even celebrated – or teased – Teresa Saporiti, who sang Donna Anna, by having Giovanni sing the word saporito (‘tasty’) four times in rapid succession. After two postponements, the opera was given on October 29. It ran for many performances, and its success led the Emperor Joseph II to command a production in Vienna. This took place on May 7, 1788; and the changes that Mozart made caused a problem that is still with us. Don Ottavio was given a new aria (‘Dalla sua pace’) in Act 1, but his Act 2 aria was replaced by an aria for Donna Elvira which followed a new comic scene for Zerlina and Leporello. Recordings and stage productions almost always conflate both Prague and Vienna, without the comic scene.

My own preference is for the original Prague version. In the composite one, Ottavio’s gentle ‘Dalla sua pace’ is an anticlimax after Donna Anna’s fiery ‘Or sai chi l’onore’, while the inclusion of both Ottavio’s ‘Il mio tesoro’ and Elvira’s ‘Mi tradì’ holds up the action which should be moving inexorably to the denouement. Moreover, one could argue that ‘Mi tradì’ is inconsistent with the portrayal of lovable, gullible Elvira, whose first appearances in each act are subverted by their being overheard by Giovanni and Leporello. Of the recordings detailed in the discography, Östman offers Prague, with the Vienna numbers in an appendix; Gardiner and Jacobs vice versa. Mackerras’s CD recording cleverly incorporates alternative versions, the cemetery scene appearing twice. Jurowski’s DVD follows Prague. The others go for the traditional conflation, Furtwängler and Sawallisch omitting ‘Dalla sua pace’.

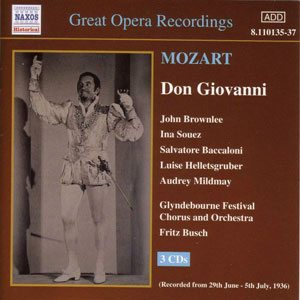

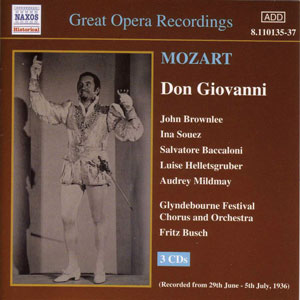

The Pioneer

There seem to be few available recordings from before the war. Unlike his 1937 Die Zauberflöte (Preiser, 1/96), Joseph Keilberth’s Don Giovanni from Stuttgart (Walhall, sung in German) is only of curiosity value. But the same year, 1936, saw the third Mozart recording conducted by Fritz Busch to emerge from Glyndebourne. Though made under studio conditions, it has all the vigour and flow of a live performance. Led by John Brownlee’s elegant Giovanni and Salvatore Baccaloni’s knowing Leporello, the performance still affords enormous pleasure. As for Busch’s superb conducting, just relish his steady tempos and – a single example – the sobbing violins in the recitative preceding ‘Mi tradì’.

Still in Mono

Skating over Wilhelm Furtwängler (to whom I’ll return in the DVD section), we come to Dimitri Mitropoulos. The hollowness of the acoustic (from the Salzburg Felsenreitschule during the 1956 festival) doesn’t detract from an excellent performance. Giovanni is sung by Cesare Siepi, who pretty well owned the part for 20 years. Like so many, before and since, he is a bass in a baritone role. His sidekick is another veteran, Fernando Corena. As recorded, there’s a slight edge – not unpleasing – to the tone of Elisabeth Grümmer’s Anna. In a starry cast that includes Lisa Della Casa as Elvira, the Ottavio of Léopold Simoneau stands out with his two arias phrased to perfection. Mitropoulos will have you on the edge of your seat with a spine-chilling orchestral crescendo before the Commendatore’s ‘Ferma un po’ in the finale. There’s a small cut in the exchange between Anna and Ottavio during the final sextet.

Siepi, Corena and Della Casa also appear in a powerful account from the New York Met in 1957 conducted by Karl Böhm (Andromeda); and it’s Siepi again in the 1962 performance from Covent Garden. Here the Leporello is the incomparable Geraint Evans, and it’s a joy to hear how he and Siepi play off each other, especially in the recitatives. Leyla Gencer is a forceful Anna, and Richard Lewis shows off his wonderful breath control in Ottavio’s arias. If you think that everything conducted by Sir Georg Solti is hard-driven, this may surprise you.

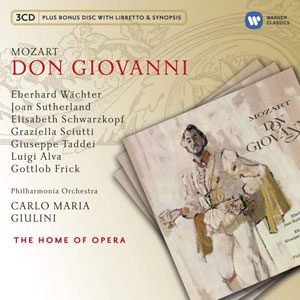

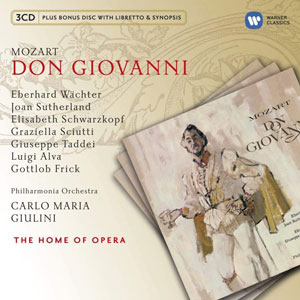

The Stereo Era

Solti’s Elvira, Sena Jurinac, had already recorded the part at least twice; for Ferenc Fricsay in 1958 she switched to Donna Anna. Irmgard Seefried is a warm, charming Zerlina, but despite the casting of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Giovanni the performance never takes wing (DG, 11/59). It’s outclassed by Carlo Maria Giulini’s recording of the following year, a set that it is almost impossible to overpraise. Eberhard Waechter and Giuseppe Taddei are excellent as master and man: the former both romantic and dangerous, the latter ironic, with a real feeling for the words in the ‘Catalogue’ aria. Joan Sutherland in full cry shows what a terrific Wagnerian she could have been, while Elisabeth Schwarzkopf proceeds from a formidable, stately entrance to a fluent, seamless ‘Mi tradì’. The Philharmonia plays beautifully and Giulini’s pacing is faultless, the balance between comedy and wistfulness just right in the trio ‘Ah taci, ingiusto core’. Another trio, the woodwind-accompanied ‘Protegga il giusto cielo’, is exquisite. And to have Gottlob Frick as the Commendatore is just the cherry on the cake. The worst that can be said is that the pauses between some of the numbers are a reminder that this is not a production from the theatre.

There were, however, two associated concert performances at the Royal Festival Hall, London, for which Sir Colin Davis stepped in. His own recording dates from 1972, shortly after he succeeded Solti at Covent Garden. It’s interesting to note that Davis follows Giulini in treating the tutti ‘Viva la libertà … la libertà!’ as one phrase, something he must have remembered from sitting in on Giulini’s recording sessions. Apart from a delayed entry at Elvira’s return to rescue Zerlina, Davis’s recording does have the feel of a theatrical performance, helped along by John Constable’s stylish harpsichord continuo. The woodwind chortle delightfully in the ‘Catalogue’ aria, and the strings in ‘Ah taci, ingiusto core’ are beautifully pointed. The fine cast includes a honeyed Ottavio from Stuart Burrows.

Honeyed is not the word for Nicolai Ghiaurov’s performance for Herbert von Karajan in 1970 – from Salzburg again, but this time at the Grosses Festspielhaus. Ghiaurov was another bass, and I suspect he found the part uncomfortably high: he snatches at the phrases in an overfast ‘Champagne’ aria and sounds ungainly rather than seductive in the serenade. Karajan’s speeds for their respective arias in Act 2 allow Teresa Zylis-Gara and Gundula Janowitz to phrase unhurriedly, the pianissimo reprise of the former’s ‘Mi tradì’ almost thoughtful. Splendid turns from the Welsh team of Burrows and Evans.

Another live recording from Orfeo, Wolfgang Sawallisch in Munich in 1973, was issued only recently. If Ruggero Raimondi is rather bland, Stafford Dean as Leporello is ample compensation: his dark bass, with a pleasing slight vibrato, makes for a treasurable ‘Catalogue’ aria, and his vocal impersonation of Raimondi is hilarious. Margaret Price negotiates the coloratura of ‘Non mi dir’ very well; Lucia Popp is an enchanting Zerlina and there’s a powerful Commendatore from Kurt Moll.

Back in Salzburg in 1977 in yet another venue, the Kleines Festspielhaus, the octogenarian Karl Böhm inclines to slow speeds, even in the minuets. Better too slow than too fast, but it comes across as ponderous. The voices are often distant, and the flow of the action is not helped by the disc change after the unmasking of Leporello. Nearly 20 years later, in 1995, Sir Charles Mackerras brings his feeling for 18th-century practice to a performance on modern instruments (but with natural trumpets): the bass minims at the beginning of the overture are shortened, the reprise of ‘Dalla sua pace’ is decorated, Masetto and the Commendatore are (as in Mozart’s time) taken by the same singer. It is all very well done, with excellent performances all round, and the layout of the alternative versions is a distinct bonus (remember to omit ‘Dalla sua pace’ for the authentic Prague experience!).

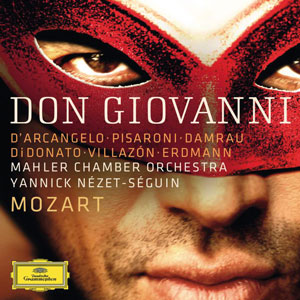

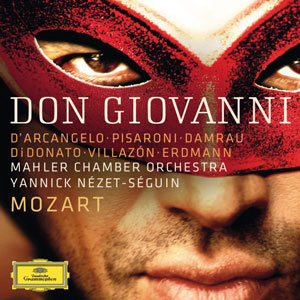

In his recording taken from concert performances, Yannick Nézet-Séguin permits some wild decoration from Diana Damrau as Donna Anna, but Mojca Erdmann embellishes Zerlina’s arias charmingly. Joyce DiDonato is dignified, even regretful at the opening of ‘Non ti fidar, o misera’. Her wonderful ‘Mi tradì’ is succeeded by a no less intense ‘Non mi dir’ from Damrau. Luca Pisaroni delivers a serious, almost sinister ‘Catalogue’ aria, and Rolando Villazón brings a welcome virility to ‘Il mio tesoro’. The subtlety of Nézet-Séguin’s conducting is breathtaking.

Period-Instrument recordings

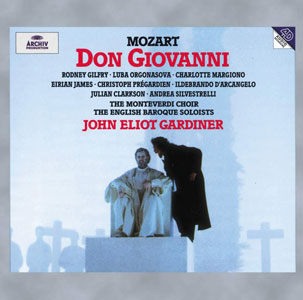

The trailblazer here is Arnold Östman’s 1989 recording from Drottningholm. As noted above, it is Prague plus Vienna appendix; but Elvira’s recitative ‘In quali eccessi’ has been omitted, presumably in order to squeeze the opera on to two discs. Östman’s tempos range from fast to turbocharged, the whole opera (excluding the appendix) over in less than two and a half hours. It’s all a bit too much. Sir John Eliot Gardiner in 1994 is a much safer bet, though if you want the Prague version you need to programme tracks 17 to 21 and 9 (not 8) to 16 on CD3. Like Mackerras, Gardiner shortens the bass minims in the overture (and again in the Act 2 finale). Rodney Gilfry is soft and intimate in ‘Là ci darem la mano’, forceful elsewhere, with Ildebrando D’Arcangelo a properly bass Leporello. Luba Orgonášová is made to take the Allegretto of ‘Non mi dir’ so fast as to trivialise Anna’s (admittedly tiresome) despair. Charlotte Margiono, on the other hand, is a gentle, unhysterical Elvira, beautifully sung. The recording from the Ludwigsburg Festival has all the tension and flow of a theatre performance. (I recall the concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, when Andrea Silvestrelli’s Commendatore marched down the steps of the auditorium with three trombones in tow.)

Twelve years on, René Jacobs also opts for the Vienna version. Others will enjoy his very individual conducting more than I do. He plays about with the tempo in Masetto’s aria, speeds up at the end of Giovanni’s ‘Metà di voi qua vadano’, slows down when Ottavio and Anna enter in the sextet, and speeds up again at Leporello’s ‘Perdon, perdono’. Apart from an unthreatening Commendatore, the cast does well and the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra is splendid. As so often in Jacobs’s work, the continuo player is hyperactive: he twiddles throughout, and introduces the cemetery scene as though accompanying a silent film.

Jacobs finds a ready disciple in Teodor Currentzis (2015), who offers the composite version including, unusually, the scene for Zerlina and Leporello, with a gratuitous solo violin added to the recitative. The accompaniment to the serenade becomes a duet for lute and fortepiano. But there are enough good moments – Anna bursting headlong into ‘Or sai chi l’onore’, the repose of ‘Protegga il giusto cielo’ – to make this worth hearing.

Don Giovanni on DVD

First up is Herbert Graf’s production, filmed by Paul Czinner in the Salzburg Felsenreitschule under studio conditions. The conductor is Wilhelm Furtwängler, recorded only a few months before his death in November 1954. I’m not sure if it’s lip-synched: we certainly see the great man conducting the orchestra ‘live’. The cast includes the young Walter Berry as a dangerous Masetto and Cesare Siepi in his prime, playing Don Giovanni as an Errol Flynn swashbuckler. He and Otto Edelmann horse about amusingly in ‘Ah taci, ingiusto core’, but one rather misses the laughter of an audience. Grümmer and Della Casa are wonderful. It’s an old-fashioned production in faded colour: not a first choice, but not to be missed. Neither is the 1978 film by Joseph Losey, shot in Venice and Vicenza, mainly in Palladio’s Villa Rotonda. The Mozart scholar Julian Rushton consigns it to a category of ‘elegant imbecilities’, but I find it a beautiful and imaginative production, respectful of the score in a way that Zeffirelli’s film of Otello is not. The prerecorded Paris Opera Orchestra under Lorin Maazel is no great shakes, but the singing and acting are excellent. The secco recitatives were recorded ‘live’. The sinister, silent valet in black is an unnecessary addition, but not annoying enough to spoil the whole.

Sir Peter Hall’s 1977 Glyndebourne production (ArtHaus; conductor Bernard Haitink) is valuable for preserving the interpretations of Benjamin Luxon and Stafford Dean as Giovanni and Leporello, but the Regency setting doesn’t feel right – and the subtitles are woefully out of synch. (Haitink returned to the opera six years later with his Gramophone Award-winning audio recording – EMI/Warner, 7/84.) The subtitles in Michael Hampe’s 1991 production from Cologne are pretty erratic too, as well as being approximate. But, conducted by James Conlon, this is well worth investigating as an example of a traditional, no-nonsense staging that’s visually arresting (Elvira appears on her balcony in a lovely golden-brown light). Thomas Allen, with mandolin (not a given, these days), sings an exquisite serenade.

Two productions come from Covent Garden. The first (2008), conducted by Charles Mackerras, is the better. Francesca Zambello’s direction has its oddities (Giovanni is bare-chested at his own dinner party; the Commendatore appears as himself, not as a statue) but in general is straightforward. Simon Keenlyside as Giovanni has a nice line in witty or humorous asides. DiDonato’s Elvira, bent on revenge, makes her entrance with a musket as well as a telescope. She takes ‘Mi tradì’ a semitone lower, sanctioned by Mozart, as she does for Nézet-Séguin: heartfelt and beautifully controlled. Six years later, Kasper Holten’s production was very well filmed by Jonathan Haswell, the singers’ facial expressions always a delight. The sets and video designs are clever and imaginative. There’s too much eavesdropping, though: Giovanni observes many of the arias, including Elvira’s ‘Mi tradì’ and Anna’s ‘Non mi dir’. Nicola Luisotti conducts well, but he should not have agreed to the huge cut in the final sextet. At the end, Mariusz Kwiecien is alone, miserable and fearful.

Vladimir Jurowski at Glyndebourne (2010) follows the Vienna version to the letter, including (uniquely, as far as I know) a shorter passage for the characters arriving after Giovanni’s demise, and the complete omission of the following duet. The setting is Franco’s Spain in 1960: dark glasses, white dinner jackets, cigarettes, Polaroid cameras. The music at Giovanni’s supper comes from a transistor radio. Gerald Finley murders Brindley Sherratt’s unarmed Commendatore with a brick, after which he is charm itself. He is very good at showing embarrassment when Giovanni tries to deal with the other three characters in ‘Non ti fidar, o misera’. Anna Samuil’s Donna Anna is obsessed with her father, not with Giovanni; Kate Royal’s Elvira is obsessed with Giovanni to the last. And there’s excellent playing from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

It’s back to Salzburg for Sven-Eric Bechtolf’s 2014 production. Pisaroni reappears as Leporello, which he had already sung for Jurowski and Nézet-Séguin; his master (as on the latter set) is Gardiner’s Leporello, D’Arcangelo. The setting is the lobby of a hotel. Elvira sings her entrance aria behind the bar; later, a masked demon serves drinks to the masked trio and, now in cloak and topper, enables Giovanni to escape his accusers. Anna gets aroused while recounting Giovanni’s attempt on her virtue; Zerlina and Masetto strip down to their underwear during ‘Vedrai, carino’. Christoph Eschenbach is well served by his singers and the Vienna Philharmonic; Anett Fritsch’s ‘Mi tradì’ is the nearest to Elizabeth Vaughan’s at Covent Garden years ago – the most passionate, despairing Elvira that I can remember.

Don Giovanni is brave, defiant to the last. All but one of the other characters move on; in the end, it’s poor Elvira, retiring to a convent, who suffers the most. No single stage production can cover all the aspects of this fascinating opera, so perhaps one can get more out of it by using one’s imagination. Consequently, there’s no top DVD recommendation, and any CD recommendation comes with a caveat about the version used: Prague, Vienna or (sort of) both? I’ve omitted the real stinkers, so you can’t go far wrong with any of the recordings listed; but Giulini is still ahead of the field.

The historic choice

Glyndebourne / Busch

Naxos 8 110135/7

Glyndebourne’s pre-war recording still packs a powerful punch. Salvatore Baccaloni’s Leporello is superb, and the rest of the cast is fine. But, above all, it’s the conducting of Fritz Busch that makes the set unmissable.

The modern choice

Mahler Chamber Orchestra / Nézet-Séguin

DG 477 9878GH3

Again, it’s the conducting that is outstanding here, with Yannick Nézet-Séguin clearly a born Mozartian. Led by Ildebrando D’Arcangelo and Luca Pisaroni, the singers give their all, with a flawless ‘Mi tradì’ from Joyce DiDonato.

‘Historically informed’ choice

English Baroque Soloists / Gardiner

DG Archiv 445 870-2AH3

Mackerras’s CD version certainly qualifies; but for performance on ‘original’ instruments the palm goes to John Eliot Gardiner with his excellent cast and the sense of a live performance.

The top choice

Philharmonia Orchestra / Giulini

EMI/Warner 966799-2

Nearly 60 years on, this is still wonderful. In addition to those mentioned above, the cast includes Graziella Sciutti, Piero Cappuccilli and Luigi Alva. Giulini (a late replacement for Klemperer) can’t be faulted. For a more ‘theatrical’ affair, try Davis.

Selected Discography

Recording Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1936 Brownlee, Baccaloni, Souez, Helletsgruber; Glyndebourne Op / Busch Naxos; Warner Classics

1954 Siepi, Edelmann, Grümmer, Della Casa; VPO / Furtwängler DG

1956 Siepi, Corena, Grümmer, Della Casa; VPO / Mitropoulos Sony; Myto

1959 Waechter, Taddei, Sutherland, Schwarzkopf; Philh Orch / GiuliniEMI/Warner; Alto; Regis

1962 Siepi, Evans, Gencer, Jurinac; Royal Op, London / Solti Royal Opera House Heritage; Opera d’Oro

1970 Ghiaurov, Evans, Janowitz, Zylis-Gara; VPO / Karajan Orfeo

1972 Wixell, Ganzarolli, Arroyo, Te Kanawa; Royal Op, London / C Davis Philips

1973 Raimondi, Dean, M Price, Varady; Bavarian St Orch / Sawallisch Orfeo

1977 Milnes, Berry, Tomowa-Sintow, Zylis-Gara; VPO / Böhm DG

1978 Raimondi, Van Dam, Moser, Te Kanawa; Paris Op / Maazel Second Sight

1989 Hagegård, Cachemaille, Auger, D Jones; Drottningholm Court Th Orch / Östman Decca

1991 Allen, Furlanetto, James, Vaness; Cologne Gürzenich Orch / Conlon ArtHaus

1994 Gilfry, D’Arcangelo, Orgonášová, Margiono; EBS / Gardiner DG Archiv

1995 Skovhus, Corbelli, Brewer, Lott; SCO / Mackerras Telarc

2006 Weisser, Regazzo, Pasichnyk, Pendatchanska; Freiburg Baroque Orch / Jacobs Harmonia Mundi

2008 Keenlyside, Ketelsen, Poplavskaya, DiDonato; Royal Op, London / Mackerras Opus Arte

2010 Finley, Pisaroni, Samuil, Royal; OAE / Jurowski EMI

2011 D’Arcangelo, Pisaroni, Damrau, DiDonato; Mahler CO / Nézet-Séguin DG

2014 D’Arcangelo, Pisaroni, Ruiten, Fritsch; VPO / Eschenbach EuroArts

2014 Kwiecień, Esposito, Byström, Gens; Royal Op, London / Luisotti Opus Arte

2015 Tiliakos, Priante, Papatanasiu, Gauvin; MusicAeterna / Currentzis Sony

This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to the world's leading classical music magazine, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe