The specialist's guide to offbeat 18th-century symphonies (with ten essential recordings)

Nalen Anthoni

Monday, January 15, 2018

We’re familiar with symphonies by the big-name composers of the era, but Nalen Anthoni sifts through the many thousands written during that time to find some remarkable lesser-known ones from around Europe

Startling but true: 16,558 symphonies were written between roughly 1720 and 1800 – the fact established by Jan LaRue after 34 years’ research and recorded in his Catalogue of Eighteenth-Century Symphonies (Indiana University Press: 1988). Mixed in with the familiar are more than 1500 composers whose works musicologist Neal Zaslaw believes were not exclusively for the aristocracy but were also ‘written in or for … the monasteries, the cities, the towns and the villages of central and eastern Europe’.

Social transformation had changed the established order, garnered new audiences. Two styles – church and private chamber – that until then had circumscribed music to a fixed purpose lost their dominance. In came ‘concert style’: public, offbeat and out of sync with court or ecclesiastical conventions, freeing composers from former constraints. Creative autonomy ruled. Radical? Sure. But structure and instrumentation were based on Italian opera, its fast–slow–fast opening sinfonia, the da capo aria (model for sonata form?) and a band of strings with pairs of oboes and horns setting the pace. In time the sinfonia breached its origins and confines, expanding its instrumentation and adding a minuet and trio as well. The four-movement symphony had arrived.

Nevertheless, every fin de siècle brings change. As Haydn was reaching his own symphonic pinnacle, tremors of a quake were being felt, exploding in two peremptory chords opening the Eroica Symphony (1803) – Beethoven’s hurtling skid into a new road, a new dawn and a new story.

But there is an old, largely unknown story too, of hundreds of composers abandoned by posterity. Here are 10 from a wide area of Europe, each one represented by a striking example of individuality, and all in performances of striking merit. Six have no alternative versions. Four – of Marsh, Gossec, Rosetti and Kraus – outstrip rivals in insight. Portrayed in a microcosm of the 18th century are its gifted composers and their symphonies, emerging in these interpretations as enterprising, eccentric, experimental – and exciting.

Essential Recordings

Erskine, Earl of Kelly Periodical Overture No 17

Hanover Band / Graham Lea-Cox

ASV (10/01)

A titled Scotsman at an elector’s court? Indeed. Thomas Erskine spent several years studying with Johann Stamitz, ‘father’ of the Mannheim School. Concerts at the court were noisy affairs – music a mere accompaniment to social activity. The horns in this 1767 overture (alias Sinfonia) of three movements (on a disc that includes music of five other 18th-century British composers) are raucous enough to quell the rowdiest audience.

Dussek Sinfonia in G, Altner G4

Helsinki Baroque Orchestra / Aapo Häkkinen

Naxos (A/12)

Three movements; strings, oboes and horns only – nevertheless, perceive a symphony in embryo. Atypically, though, the symphonies of Bohemia-born František Xaver Dušek didn’t reach a wide public. Allan Badley reckons certain patrons had restricted their distribution. This work, though modestly scored, is substantial in content, and the brass parts offer a reminder that the ancestor of Dušek’s first patron, Count Sporck, brought the horn to Bohemia in 1681.

Vaňhal Sinfonia in D, Bryan D17

Nicolaus Esterházy Sinfonia / Uwe Grodd

Naxos (4/00)

Johann Baptist Vaňhal – dogged by malice though he was – was important as a leading symphonist of the day, and this was recognised by Jan LaRue, HC Robbins Landon and specialist Paul Bryan. Listen from the two-minute opening Andante molto in D minor and engage with a work (composed c1779) both grand and profound. The unusual sonority of wind parts scored exclusively for oboes and trumpets enhances its significance as a symphony in all but name.

Kozeluch Symphony in B flat, ‘L’irresoluto’

Concerto Köln

Warner Classics

‘Too pleased with himself … repeats himself or dwells too long in one place’ was an accusation made against Leopold Kozeluch. Yet JF Ritter von Schönfeld also complimented him on ‘some very beautiful symphonies’ (A Yearbook of the Music of Vienna and Prague, 1796). L’irresoluto (1780-90) bends formality to reveal, in a performance of finely graded textures and dynamics, a haunting beauty seemingly arising from dwelling on irresolution – until a resolute dominant–tonic ending.

Brunetti Symphony No 36 in A

Concerto Köln

Capriccio (7/95)

Solemn A minor Largo precedes capricious A major Allegro di molto first movement with false recapitulation. Immediately corroborated is Newell Jenkins’s verdict that this symphony is ‘certainly one of the most curious and exceptional of all [Gaetano] Brunetti’s works’. Then there is his unique hallmark – of minuet and trio invariably discarded for a wind Quintetto (here in A) plus a trio for strings (A minor), both in 2/4. Revel in discovery.

Marsh Symphony No 6 in D

The Chichester Concert / Ian Graham-Jones

Alto (2/90)

You’ve probably heard it said that John Marsh was an amateur. Yet he rode over English reserve and Handel’s still potent influence to espouse the new genre sweeping through the rest of Europe. And there is nothing of the dilettante in this 1796 symphony (he composed 39, only some of which have survived), his second in four movements of which the third is a minuet of Handelian pomp probably intended to soften resistance. Nice one, that.

Gossec Symphonie à grand orchestra, ‘La Chasse’

Concerto Köln / Werner Ehrhardt

Capriccio

From farmer’s boy in Belgian Hainaut to Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris, François-Joseph Gossec adroitly circumvented political and social turmoil to mould a fulfilling career for most of his 95 years. He was among the first in France to use clarinets, heard in this riotous four-movement, two-minuet contribution (c1773) to a booming art form – hunting calls and frequent galloping rhythm enacting an age-old sport popular at the time.

Rosetti Symphony in G minor, Kaul I:27

Concerto Köln

Warner Apex (12/95)

Antonio Rosetti joined the court of Oettingen-Wallerstein as servant and double bassist, rising to Kapellmeister. This symphony (1787), forceful yet lyrical, with minuet and trio placed second, is one of many written for an orchestra noted for precision tied to meticulous control of tonal nuance. Distinctive wind writing also epitomises Rosetti’s confidence in principals like Alois Ernst (flute), Christoph Hoppius (bassoon), Franz Zwierzina and Joseph Nagel (horns). Wallerstein’s excellence resounds in this recording.

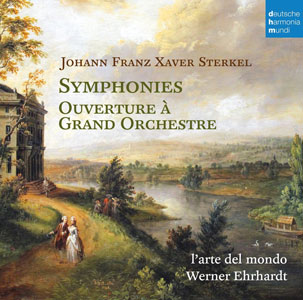

Sterkel Symphony in D, Op 35 No 1

L’Arte del Mondo / Werner Ehrhardt

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi

Remember the intimation of tremors? Their beginnings, from content and expression to adding extra directions for tighter beats in a pre-metronome era, came largely from Johann Franz Xaver Sterkel, whom Beethoven revered. Markings of Allegro con spirito and Allegro vivace as in this symphony (1792) were rare; Allegro for a minuet turned scherzo, very rare. No more. Beethoven learnt from such origins and innovations – and incorporated them into his own originality.

Kraus Sinfonie in C minor, ‘Symphonie funèbre’

Concerto Köln

Capriccio (9/93)

Not an orthodox symphony but one symphonic in amplitude, mirrored in Concerto Köln’s touching performance. All four movements are slow, evincing the grief of Joseph Martin Kraus, who on the night of March 16, 1792, witnessed an assassination attempt on his patron King Gustav III of Sweden at a ball. The king died a couple of weeks later, and this music was commissioned to accompany the coffin from palace to church. It is sombrely orchestrated, for pairs of clarinets, bassoons and trumpets, four horns, strings and timpani, brass muted (con sordino) and drums muffled (coperto). Strings play the third-movement Chorale, a four-part arrangement of the Swedish hymn ‘Let us bury this body’. An anguished nation bids farewell.

This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Gramophone. To enjoy similar articles every month subscribe to Gramophone, the world's leading classical music magazine: gramophone/subscribe