Reputations: Bernard Herrmann

Gramophone

Monday, February 20, 2017

Despite his struggle for acceptance in the concert-hall, Herrmann's triumphs on the cinema screen secure him a place in the composer's pantheon, argues Nick Shave

'Film music is significant in many ways, of course, but not as music, which is why the proposition that better composers could produce better film music is not necessarily true: the standards of the category defeat high standards.' With these words, Igor Stravinsky not only justified his own unsuccessful attempts to marry music with image, but also articulated the commonly held view that such marital affairs produce music's feeblest offspring. In nearly a century of alliances between high art and Tinsletown commerce, only a handful of film composers have been deemed worthy of serious consideration by film and music critics. Bernard Herrmann (1911-75) has earned the respect of both. Few deny Herrmann's contribution, both as a film composer and outspoken advocate of his craft. Fewer still are capable of fusing image and sound with the same degree of craftsmanship.

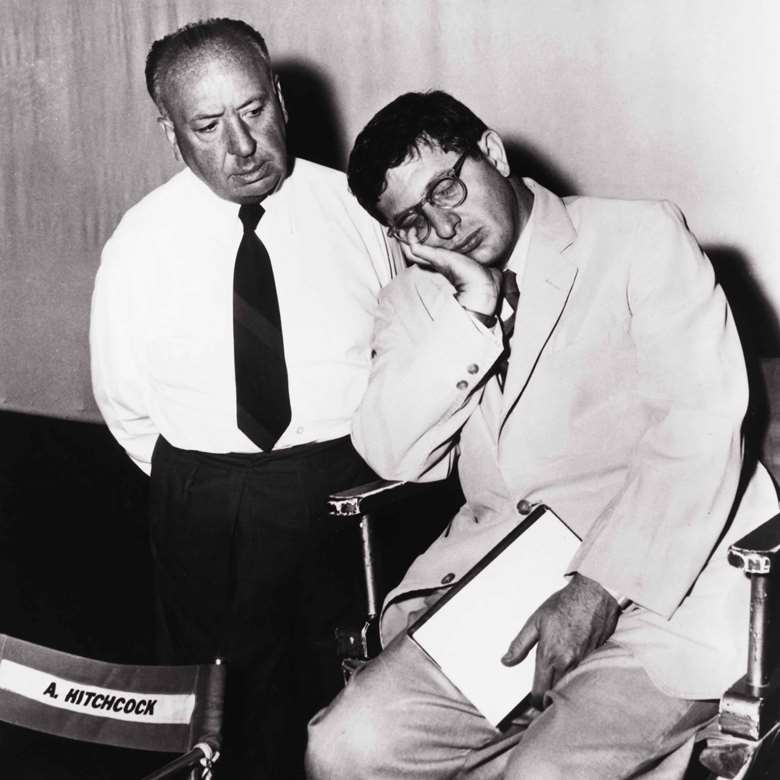

If he were alive today, Herrmann might well frown upon the sound-drenched blockbusters; the artless noise of horror; the pop songs that jar on screen (but sell by the bucket-load) and his own recent contributions to Hollywood's new releases. Since his death, his themes have played out on dozens of new releases, more than two-thirds of which draw upon his scores for Alfred Hitchcock. His screeching strings for Psycho's shower scene are dredged up more regularly than the guests of the Bates Motel, embedded in the popular psyche as the archetypal sound of horror. Whether referenced to raise a laugh, as in Pixar's animation Finding Nemo, or repeated in earnest, as in Gus Van Sant's colour Psycho remake (1988), it all bodes badly for Herrmann, whose lifelong aspiration to establish his reputation as a composer who wrote for film - not Hitchcock's film composer - seems more pedantic and wrong-headed by the day.

Cast your ears back to New York's jazz age, however, and you begin to hear how Herrmann's reputation has swung out of line. He made his earliest attempts at writing opera at the age of 12, before studying composition and conducting at New York University and then at Juilliard. As a conductor, he championed new music, in particular Charles Ives, in whom he discovered 'the fundamental expression of America...a brooding introspective and profoundly philosophic temperament'. Forward thinking, Herrmann was drawn to the mavericks of his time, as well as to the jazz that inspired his friends Aaron Copland and George Gershwin and would later play out in his urban themes for Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver.

At the same time as joining CBS as head of educational programmes in 1934, Herrmann had high hopes of becoming a world-class conductor. It wasn't to be. After cultivating the opportunity to conduct the New York Philharmonic in 1947, his two concerts at New York's Lewissohn Stadium were critically slammed. His largescale concert-hall works - the foundations of his repertoire – were too savagely deconstructed: despite advocacy from John Barbirolli, The New York Times declared his cantata Moby Dick to be 'pretentious and ineffectually noisy'; his Symphony fell short of Philadelphia Orchestra conductor Eugene Ormandy's requirements by being, in the conductor's view, 'about 15 minutes too long'. Despite repeated attempts to stage his opera Wuthering Heights, it was only after his death the Portland Opera Company would give its world premiere. Forty-five minutes of the opera were axed for its performance.

So was Stravinsky correct after all? Was Herrmann's struggle for acceptance in the concert hall a sign that he actually belonged to the cinema, where music goes unnoticed? Several of the world's conductors - such as Esa-Pekka Salonen - and performers - Dame Kiri Te Kanawa - who have placed his film themes at the foreground in their recordings, clearly think not. True, the longevity of Herrmann's scores has pivoted upon the quality of the films he wrote for, yet even when placed out of context, the affective qualities of his themes show few signs of diminishing. When blonde assassin, Daryl Hannah, whistles Herrmann's theme-tune from Twisted Nerve, in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill, Part 1, we needn't have seen the bloodshed of Roy Boulting's late-sixties horror to smell a whiff of sadism in the air.

Similarly, his shower-scene screeches in Finding Nemo are enough to express a melodramatic moment of anxiety without the aid of Norman Bates. In short, Herrmann's music speaks for itself.

Or rather, his 60-odd film scores rely as much for their affective qualities upon their visual associations as they do upon his supreme command of tone colour. Beginning with his first film score, Citizen Kane (1941), he eschewed Hollywood's practise of painting in broad orchestral brush strokes and applied instrumental colours only where they were needed - and by whatever means. Electronic violins and the recorded sound of singing telephone wires were drawn into his soundtrack for The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941); the weird whine of the theremin ushered in the future sound of sci-fi in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and the orchestra was stripped down to monochrome strings in Psycho (1960). Herrmann's music presents a logical extension to French Impressionism in which sonorities find their visual analogies on screen. 'Debussy said that cinema would allow the perfect creation of poetry, vision and dreams,' he once pondered. 'If Debussy had lived long enough into the era of the sound film, who knows what he would have created.'

In his Hitchcock collaborations, in particular Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959), Herrmann hit the apex of his dramatic style, with large-scale tonal processes playing a key role in bridging the emotional gap between audience and on-screen psychology. In his study of Herrmann, Hitchcock and the Music of the Irrational (Cinema Journal 21:1982) Royal S Brown finds that 'the essence of Herrmann's Hitchcock scoring lies in a harmonic ambiguity whereby the musical language familiar to Western listeners serves as a point of departure, only to be modified in such a way that expectations are held in suspense for much longer periods of time than [we] are accustomed to'. With film providing the foundations on which Herrmann could arrange his ideas, the composer was free to stretch the tonal ambiguities of post-Wagnerian harmony to their most dramatic conclusions. Should we not, then, regard his unresolving dissonances the diminished sevenths and augmented triads of Vertigo, or the unsettling tritone of Psycho's finale - as tonality in its most manipulative guise?

While embracing the French school and exhibiting a mastery of pastiche, Herrmann's feet were firmly planted in the German Romantic tradition. Highly strung, paranoiac, and suffering recurring anxieties about death, he found in film 'a great opportunity to express myself'. His sense of nostalgia, too, pervades the sighing motifs of his scores. Ironically, it was the same personal traits that hampered his prospects in the concert hall that were also at the root of his achievements on screen. While his taciturn manner on the concert podium could bring out the worst in his players, it was also indicative of his capacity for pain, rejection and his obsessive quest for perfection. As friend and film composer, Elmer Bernstein recalls: 'He was a loving person and an angry person too, angry about incompetence and angry with people who didn't understand the art. It's just as well he didn't live to see what's going on today'.

Truth is, Herrmann's outlook on the future of film music was as bleak as Stravinsky's view of his time. In his last interview with Sight and Sound magazine he bemoaned the demise of his art. 'The art of writing music for films is close enough to extinction...because the new people coming into it simply haven't got the technical know-how,' he claimed. True, he had suffered the painful consequences of a break with Hitchcock (who had axed his score for Torn Curtain) and no doubt felt the need to assert his authority following a lull in his career. But what Herrmann called for was, at the very least, a distinction between the business of penning muzak for celluloid and the craft of marrying sound with image. In putting his beliefs into practice, he created dramatic music that's not only worth hearing, but also worth a closer listen.

This article originally appeared in the May 2004 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe