The story behind the triumphant premiere of Handel's Messiah

David Vickers

Friday, April 10, 2015

On April 13, 1742, Handel's ever-popular oratorio received its premiere in Dublin

The tradition connecting Messiah with Christmas owes nothing to the oratorio's origins. The judicious compression of scriptural references to Jesus Christ was carefully designed by Charles Jennens, a Shakespeare scholar who was educated at Oxford. Jennens never gained a prominent position in society because he refused to take the vow of allegiance to the House of Hanover, and he also objected to the deposed House of Stuart's Catholicism. Jennens was a keen champion of Handel's music since at least 1725, when he ordered a copy of the printed edition of Rodelinda. By the mid-1730s, Jennens was personally acquainted with Handel, and he probably provided the libretto for Israel in Egypt (1738). In July 1741, Jennens wrote to his friend Edward Holdsworth: 'Handel says he will do nothing next Winter, but I hope I shall perswade him to set another Scripture Collection I have made for him, & perform it for his own Benefit in Passion Week. I hope he will layout his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excell all his former Compositions, as the Subject excells every other Subject. The Subject is Messiah.'

Jennens intended Messiah as a statement of faith in Christ's divinity, in reaction to the increasing popularity of rationalised atheism. It is difficult to discern what Handel thought about religion, but attractive legends such as him weeping over the score of Messiah are apocryphal. He composed it between August 22 and September 14, 1741, but the speed of its composition compares to Handel's normal rapidity and cannot be attributed to either divine or artistic inspiration: within days Handel started work on Samson, adapted from Milton's Samson Agonistes by Newburgh Hamilton, and that oratorio was also complete in its first draft by the end of October. Jennens arrived in London at the end of November 1741, and was surprised to discover that Handel was not there. Jennens wrote 'I heard with great pleasure at my arrival in Town, that Handel had set the Oratorio of Messiah; but it was some mortification to me to hear that instead of performing it here he was gone into Ireland with it.'

Not much is known about Handel's sudden acceptance of an invitation to perform in Ireland, but it was probably offered by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire. Handel's last two Italian operas, Imeneo and Deidamia, were both failures with fickle London audiences. Perhaps Handel foresaw abandoning the genre in Italian and concentrating upon theatre works in English. During this uncertain transition, the invitation to give a season of concerts at Dublin granted Handel an opportunity to escape the pressure in London and to consider his future.

Dublin had an active theatre and concert life and Handel's visit coincided with the opening of a new concert venue, the Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street, where Handel gave two performances each of L'Allegro, Acis and Galatea and Esther between December 1741 and February 1742. Handel only brought over the soprano Avolio and a few assistants from London, but the Lord Lieutenant's court at Dublin Castle boasted a small orchestra, and numerous professional singers worked at theatres and in the city's two cathedrals. These local musicians formed the core of Handel's musicians and the first series of subscription concerts was an enormous success. He was persuaded to stay longer than planned and produced another concert series which included Alexander's Feast and Hymen, an unstaged serenata adapted from Imeneo. This was Handel's last performance of an Italian opera.

The second series of concerts finished on April 7, 1742, but Handel was hungry to capitalise on his eager audience, so he arranged the first performance of Messiah for April 13. Expectation was high: the rehearsal on April 12 was ticketed and the following morning excited newspapers reported that the oratorio 'far surpasses anything of that Nature, which has been performed in this or any other Kingdom'. Advertisements requested that Ladies attend 'without Hoops', and that 'Gentlemen are desired to come without their swords' in order to increase the capacity of the hall. Handel estimated that the venue could hold 600, but an extra 100 people crammed in.

The premiere of Messiah was a triumph. The alto soloist, Susanna Cibber, was an actress who had attracted scandal in the past, but legend has it that her emotional performance of 'He was despised' moved Dr Patrick Delany – the husband of one of Handel's most ardent champions - to exclaim 'Woman, for this, be all your sins forgiven'. The Dublin Journal's review proclaimed that 'the best Judges allowed it to be the most finished piece of Musick. Words are wanting to express the exquisite Delight it afforded to the admiring crouded Audience. The Sublime, the Grand, and the Tender, adapted to the most elevated, majestick and moving Words, conspired to transport and charm the ravished Heart and Ear.'

Recommended recordings

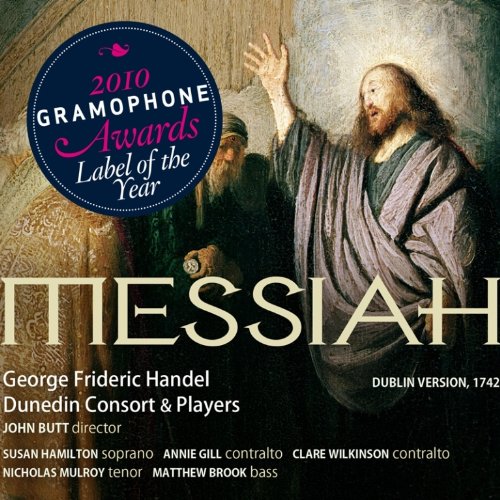

Hamilton, Gill, Wilkinson, Mulroy, Brook; Dunedin Consort / John Butt

(Linn Records)

'Comfortably the freshest, most natural, revelatory and transparently joyful Messiah I have heard for a very long time' Read review

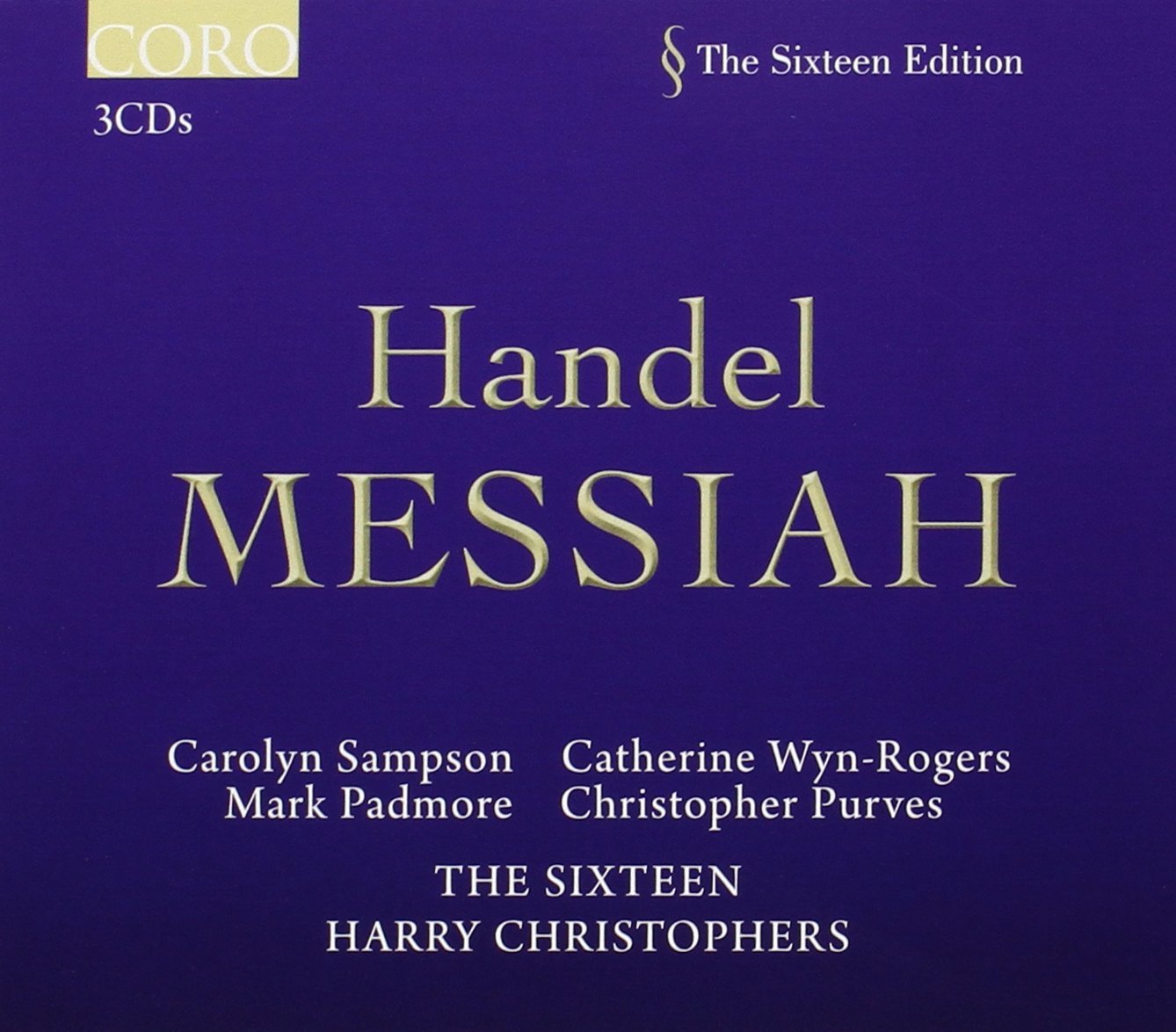

Sampson, Wyn-Rogers, Padmore, Purves; The Sixteen / Harry Christophers

(Coro)

'A safe recommendation for anyone wanting to acquire an all-purpose “period” Messiah.' Read review

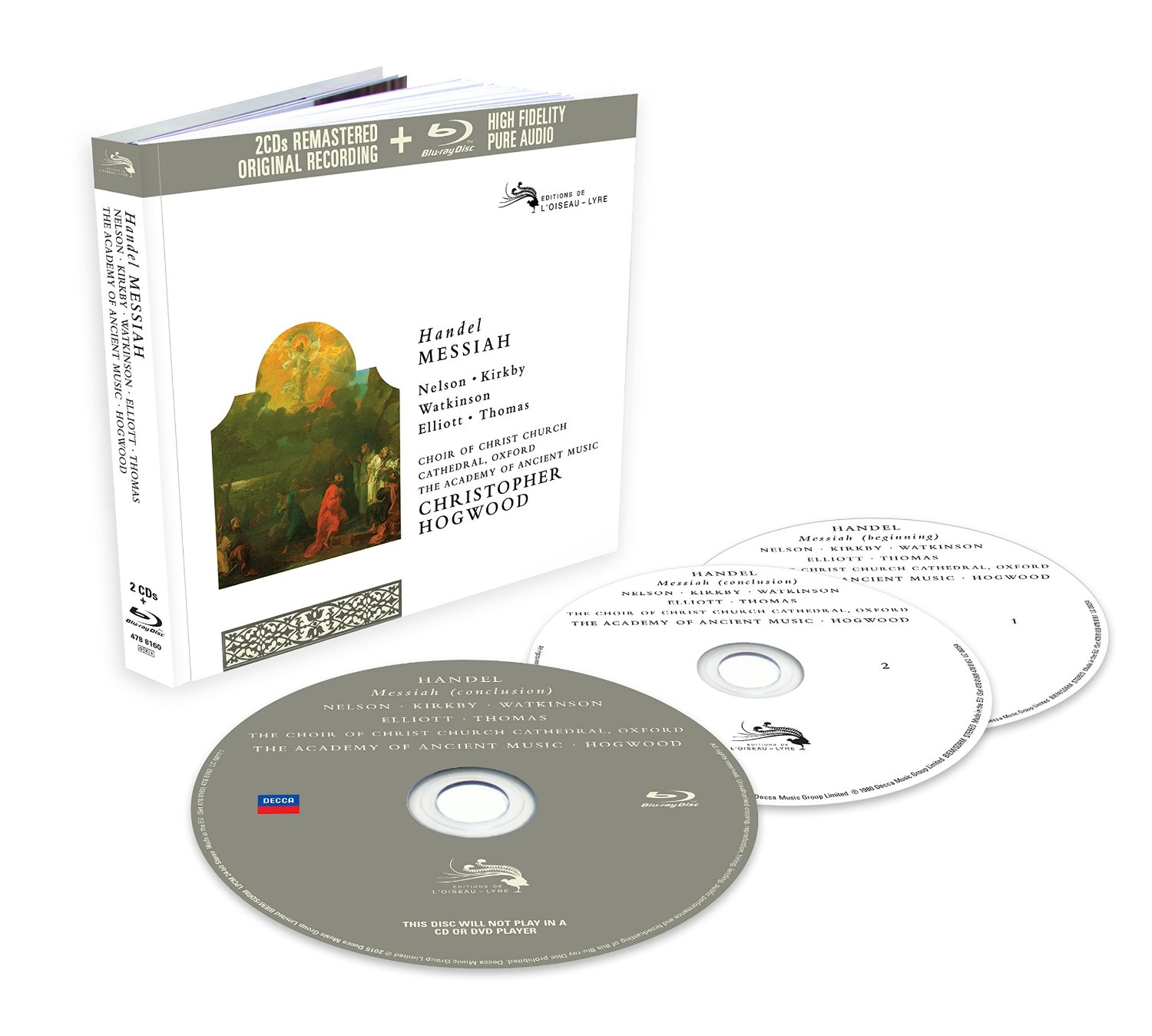

Nelson, Kirkby, Watkinson, Elliott, Thomas; Christ Church Cathedral Choir, Academy of Ancient Music / Christopher Hogwood

(Decca/L'Oiseau Lyre)

'One of the most deeply convincing Messiahs we have' Read a discussion of the Hogwood recording by Lindsay Kemp and David Vickers

This article originally appeared in the December 2004 issue of Gramophone.