Viva Latin America!

Gramophone

Thursday, August 4, 2016

With the Proms and the Olympics focusing on Latin America this year, Andrew Farach-Colton explores the vibrancy of the area’s music and asks why certain composers aren’t better known

Gustavo Dudamel and the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra perform a free concert in Caracas in 2009 ©Carlos Garcia Rawlins/Reuters

Latin America’s burgeoning international impact has been felt in literature, cinema, the visual arts, pop music and cuisine over the past half-century, yet the classical music from that region still remains relatively unknown. Ask your average European concert-goer to name some prominent US composers and they’ll likely provide a fairly accurate shortlist with little trouble: Gershwin, Copland, Bernstein, certainly; perhaps also Barber, Glass; even Ives and Adams. Ask these same concertgoers for some composers from south of the border: well, there’s Villa-Lobos, maybe Ginastera, and, hmm…does Piazzolla count?

A thorough explanation of this imbalance would be book-length at least, but the obvious short answer is that, while the US has wielded enormous economic and political clout for more than a century, the 20-odd countries that make up Latin America have struggled for stability, and have been used by the superpowers as pawns in an often deadly post-Cold War chess game. In reality, musical culture on both continents has developed more or less in tandem. Composers in the 18th and 19th centuries strived to emulate European trends before finding more distinctive, nationalist styles in the early decades of the 20th century. Yet North American composers have achieved an international reach and recognition that none of their southern peers can rival.

For stark evidence of this disparity, consider Heitor Villa-Lobos, arguably the best-known of all Latin American composers. Granted, the Brazilian was an astonishingly prolific figure whose catalogue is bursting with well over 2000 works. Yet today, more than a half-century after his death, only a small fraction of his output is performed regularly or is accessible on recordings, and there’s still a significant segment that remains unpublished. Marin Alsop, the American-born music director of the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, sums up the situation succinctly: ‘We only really know the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Villa-Lobos.’ Her colleague Arthur Nestrovski, the orchestra’s artistic director and a composer in his own right, notes that even in Brazil, much of Villa-Lobos’s work remains unknown. ‘Of course, many people know the Bachianas Brasileiras and may also be familiar with the series of Chôros, but the symphonies? We are actually in the process of recording his complete symphonies for the first time.’ Nestrovski explains that several of the symphonies exist only in error-ridden manuscript copies, which may help to account for the neglect of an obvious 20th-century master. ‘And beyond the symphonies,’ he adds, ‘there are still so many other wonderful works of his that are yearning for our attention.’

There's nothing genteel about Latin American music. It may be beautiful, sensual or melancholic, but it can also be brutal or painful – Gabriela Montero, pianist

Villa-Lobos’s Six Preludes and 12 Etudes for guitar are among his most frequently performed and recorded works, which may speak to the relative success of the Latin American guitar repertoire. Cuban-born Manuel Barrueco, who has been championing Latin American composers from the outset of his career in the 1970s, goes so far as to say that Villa-Lobos could be the greatest composer ever to have written for the guitar. ‘It’s not just the quality of the compositions, which are absolutely gorgeous, but also the way in which he exploits the instrument,’ he says. ‘He gets so much sound from the guitar. Moving the left hand in one position up and down the fingerboard, combined with the use of open strings, creates these fantastic harmonies and patterns – sounds that had never been imagined up to that moment. Villa-Lobos had a view of the guitar that was simply unlike anyone’s before him.’

The prominence of the guitar in Latin American repertoire reflects an ancestral bond with the Iberian peninsula and, more to the point, an intimate relationship with popular music. ‘My view is that the best aspects of Brazilian culture in the past 150 years all have to do with mixture,’ Nestrovski says. ‘Whether we’re talking about architecture, gastronomy, dance, or music – they’re all related to the blending of cultures: Native American, African, European and, more recently, North American. It’s a big pot with so many different strata that it’s difficult to define exactly what “national” really means. Everything is so mixed.’

For Alsop, this smudging of the lines separating genres and styles is tremendously exciting. ‘I love that period in North American music beginning around the 1920s and ’30s when popular and serious music came together. So having the opportunity to work in São Paulo with this rich, blended musical tradition – music that most of us North Americans or Europeans have very, very little experience with – has been a true voyage of discovery.’

It’s worth noting, however, that the ethnic make-up of each country in Latin America is different, and this is reflected in markedly distinct musical cultures. The African influence that’s so prevalent in Brazil and Cuba is almost entirely non-existent in Mexico or Argentina, for instance, where composers have forged nationalist styles using folkloric elements.

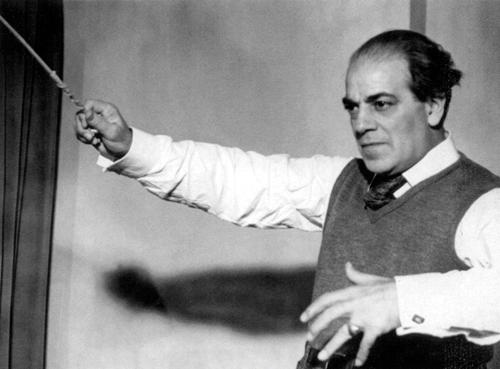

Alberto Ginastera (whose centenary is being celebrated this year) is, with Villa-Lobos, the other undisputed giant of Latin American music. But although they were near contemporaries and neighbours in a way (Brazil and Argentina share a 1200km-long border), the music of the two composers has very little in common. This was partly a matter of differing personality types. Villa-Lobos never revised, claiming that revision took time away from composition. ‘He wrote and wrote,’ says Gisèle Ben-Dor, the Uruguayanborn conductor. ‘Rivers of music came from him. He wrote in coffee shops – wherever he was. Sometimes he’d put the papers aside and they’d get lost. He was very spontaneous. Ginastera, on the other hand, was very precise. He purposely destroyed some of his music or insisted it never be performed. And he was always looking to Europe. He didn’t want to be classified as an Argentine composer, as a nationalist. He really didn’t.’

Beginning in the late 1950s, Ginastera began to incorporate experimental techniques that were being employed by European modernists, and in 1970 he moved to Switzerland, where he spent his last years. Some of the music from his self-described ‘neo-expressionist’ third period remain challenging for audiences and have perhaps ironically ensured that he is remembered primarily for his early nationalist masterpieces. Yet even in the thorniest examples of his later music, Ginastera never entirely abandons his musical heritage. ‘The incessant rhythms, magical adagios, mysterious prestos and sad cantilenas make Ginastera’s music always captivating,’ says Argentinian pianist Fernando Viani, who surveyed the composer’s solo keyboard music for Naxos. ‘Ginastera sought to validate the position of a Latin American composer who inherits a conflicted situation: the technique from the world of our colonisers and the musical roots from indigenous people who were oppressed and silenced. The deeper one digs into these roots, the more painful the conflict becomes. Ginastera’s music is always impeccably crafted, yet has a raw power, and this is what draws me to him.’ Viani continues: ‘As one who is himself the grandchild of immigrants, who’s interested in the search for identity, and who wants to believe in “magical realism”, Ginastera’s music truly fits like a glove.’

Beyond Villa-Lobos and Ginastera, which other composers are at the heart of the Latin American repertoire? Saúl Bitrán, first violinist with the intrepid Cuarteto Latinoamericano since its genesis in Mexico in 1982, has his own pantheon. ‘Along with those two, you’d have to include Silvestre Revueltas and Carlos Chávez – both Mexicans – as the composers who pretty much invented the language of Latin American concert music,’ he says.

‘Voyage of discovery’: In São Paulo, Marin Alsop relishes the ‘rich, blended tradition - music that most of us North Americans or Europeans have little experience with’ ©Amy T Zielinski/Getty Images

‘Of course, there are others who also should be mentioned: Roque Cordero from Panama, Julián Orbón from Cuba, and Juan Orrego-Salas from Chile. But the core quartet of Villa-Lobos, Ginastera, Revueltas and Chávez cannot be ignored, and all of the composers who have followed them have felt their enormous shadow and had to find their own way to do something different.’

Arthur Nestrovski mostly agrees with Bitrán’s assessment. ‘Orbón’s music is definitely worth investigating. And I would add another name: Antonio Estévez of Venezuela. He composed at least one masterpiece, the Cantata Criolla (1954), which the São Paulo Symphony performed here in Brazil for the first time last year. Scored for tenor and baritone soloists, choir and orchestra with a powerful percussion part, it’s a fantastic mixture of Stravinskian textures with rousing Venezuelan rhythms. It should be played everywhere, really, like Carmina Burana. The problem is that there’s no published score. We had to find somebody who’d played the work, get a photocopy, speak with the composer’s family. It’s complicated. I don’t think there’s ever been a recording.’

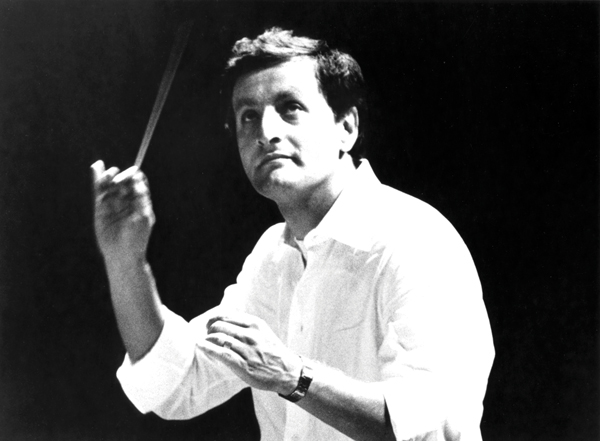

Ah, but there is a recording, though – from 1992 with Eduardo Mata conducting the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela on Dorian – and it’s a knockout in every sense. Nestrovski is absolutely right: Estévez’s Cantata Criolla should be in the standard repertoire. And here, perhaps, it’s proper to pay tribute to Mata, who died in 1995 at the age of 52 when the small airplane he was piloting crashed. Both Bitrán and Ben-Dor, unprompted and in separate interviews, make a point of singling out the effect of the late Mexican conductor’s unflagging advocacy of Latin American composers. Bitrán credits Mata with getting the Cuarteto Latinoamericano its recording contract with the Dorian label, which resulted in magnificent and invaluable recordings, made from 1995 to 2001, of Villa-Lobos’s 17 string quartets, as well as other vital projects. Ben-Dor puts it simply: ‘Mata was a pioneer. We’ve all benefited enormously from his hard work.’

Alsop, Barrueco, Ben-Dor, Bitrán, Nestrovski and Viani are, as Mata was, eager and enthusiastic guides to a large and largely uncharted repertoire, one whose ‘core’ is continually expanding. Nestrovski suggests that Camargo Guarnieri and Francisco Mignone richly deserve to take their places alongside Villa-Lobos. Listening to Guarnieri’s intricately wrought Symphony No 4, Brasília, dedicated to Leonard Bernstein, and his sophisticated and delightful (in the Tchaikovskian sense) Três Danças para orquestra, or Mignone’s boldly coloured 1933 choral ballet Maracatu de Chico Rei, it’s difficult to fathom why this music is so rarely heard. And then there’s Almeida Prado, a student of Messiaen who combined various elements of that French master’s technique with Afro-Brazilian rhythms. The São Paulo Symphony recorded a stunning suite of excerpts from Prado’s massive Sinfonia No 2: Dos Orixás (available to download for free on the orchestra’s website) which leave one impatient to hear more.

Viani makes a strong case for the music of Luis Gianneo, whom one might describe as an Argentinian Prokofiev, at least in his piano music. Gianneo’s evocative post-Impressionist orchestral tone-poem El tarco en flor should please those with a fondness for Delius and Bax. And Viani, Barrueco and Ben-Dor all express affection and admiration for the songs, piano miniatures and chamber works of Carlos Guastavino, whose use of folkloric melody creates a simple surface which barely conceals a consistent undercurrent of bittersweet, nostalgic longing.

Venezuelan pianist and composer Gabriela Montero believes that an element of suffering filters through everything Latin Americans say or do. ‘This is true of the music, too,’ she says. ‘There’s nothing genteel about it. It may be beautiful, sensual or melancholic, but it can also be brutal or painful. It’s essentially very different from European classical music.

‘One simply cannot ignore the political context, or the history of what the people have lived through,’ she continues. ‘I can’t separate that out because as a musician, that’s what drives me. I view myself as a musical storyteller, and my hope as a composer is to raise awareness – not merely to write music, but to bring to the audience a story that they might otherwise remain ignorant of.’

A renowned improviser, Montero shares an anecdote about a performance she gave in Norway. ‘When I play a solo recital, I always devote the second half to improvisations and ask the audience to provide me with the themes. Here, I was asked to create little folksongs about elves and mystical figures in the forests and lakes. It was all so innocent. At one point I laughed and said, “You know, if this was Latin America, every song would be about betrayal or jealousy – something really dark and emotional.” It’s such a different culture. In Latin America, we see and experience life in a dramatically different way.’

Recommended recordings

Experience the sheer variety of Latin American music

‘Latin America Live: The Eduardo Mata Sessions’

Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela/Eduardo Mata (Dorian)

A varied selection of Latin American orchestral masterworks, including Estévez’s thrilling Cantata Criolla. The recordings are of demonstration quality and the Simón Bolívar Orchestra play with verve and élan for the late conductor Eduardo Mata.

Villa-Lobos: String Quartets

Cuarteto Latinoamericano (Brilliant Classics)

These 17 string quartets span Villa-Lobos’s entire creative life and reveal a multifaceted and mercurial genius who never seemed to run out of ideas. A labour of love for the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, and vividly recorded by Dorian in the 1990s, this is an essential set.

Ginastera: Piano Music

Fernando Viani pf (Naxos)

Ginastera was a purposefully serious composer, yet Viani finds equal measures of joyful exuberance and expressive intimacy in this compellingly taut recording of the composer’s complete piano music.

‘Canciones Argentinas’

Bernarda Finkmez, Marcos Fink bar, Carmen Piazzini pf (Harmonia Mundi)

Here, a choice selection of Carlos Guastavino’s gemlike songs are placed in the larger context of 20th-century Argentinian canciones, all sung to the manner born by Bernarda and Marcos Fink. A delectable recital.

Mignone: Maracatu de Chico Rei. Sinfonia Tropical. Festa das Igrejas

São Paulo Symphony Orchestra/John Neschling (BIS)

This triptych of scintillating orchestral showpieces presents Mignone as a Brazilian analogue to Respighi. The exuberant choral ballet Maracatu de Chico Rei is a loveable masterpiece in its own right, and the São Paulo Orchestra and Chorus perform it with obvious gusto.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Gramophone