What is a Concerto?

Richard Bratby

Wednesday, February 8, 2023

Discover the Concerto – the variously collaborative and competitive musical form that keeps on reinventing itself

To work together – or to compete? If the word concerto is, as reference books seem to agree, derived from the Latin concertare, it’s always been about these two things. In calling his Seventh Book of Madrigals Concerto (1619), Monteverdi almost certainly meant the former; Bach meant the latter in his Italian Concerto (1735) – even though the contest is enacted by a single musician (on a keyboard). By then, the idea of a concerto involving soloists in dialogue with a larger ensemble had already taken root.

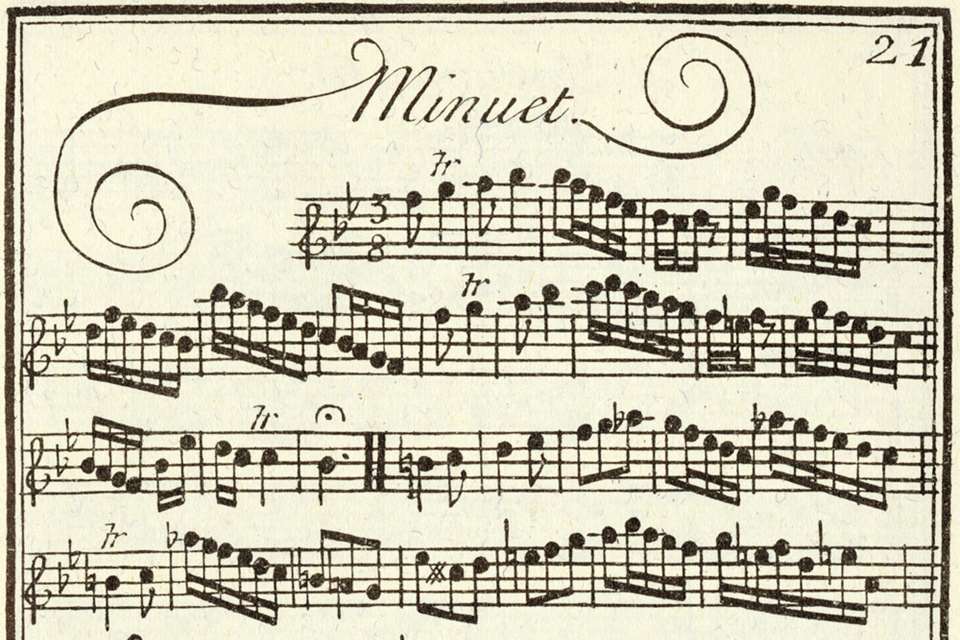

Corelli’s Op 6 set (1714) popularised the notion of the concerto grosso – in which a small group of virtuoso soloists converses with a larger ensemble – while Vivaldi’s 350-plus solo concertos (c1700-41) demonstrated to spectacular effect the musical potential when a single virtuoso performer challenges a full orchestra.

See also:

The Classical concerto

In the late 18th century, the solo concerto emerged as the dominant form: a reflection of the Enlightenment ideals of the individual and society that Mozart could express as playful conversation piece (Flute Concerto No 1, 1778), tragic drama (Piano Concerto No 24, 1786) or lyrical character study (Clarinet Concerto, 1791).

A late-century fad for the symphonie concertante – a concerto of symphonic proportions, with two or more soloists – only emphasised this trend.

The Romantic concerto

After Beethoven’s five piano concertos (1795-1810) the story of the genre would be dominated for a century by the question of how to reconcile solo virtuosity with the growing power of the orchestra and the dramatic scope of symphonic form. One approach was to outshine the orchestra with ever more dazzling solo fireworks: Paganini led the way; Liszt refined it in the 1850s.

Another approach was to tailor the form to match the solo instrument: Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto (1844) carefully rations the use of the full orchestra. But by the time Tchaikovsky had written his First Piano Concerto (1875), what he called ‘the mettlesome piano’ (in a letter of 1880) could match the orchestra on its own terms; and from Brahms’s First Piano Concerto (1858) through to Rachmaninov’s four concertos for piano (1891-1926), the late Romantic form of the genre combined supreme virtuosity with epic musical drama. Busoni’s colossal Piano Concerto (1904) is so Mahlerian that it even features a chorus.

The concerto in the 20th century

In the 20th century, technical skill on all instruments developed to such a peak that previously unthinkable concertos were now possible. Concertos for marimba (for example by Paul Creston, 1940), tuba (Vaughan Williams, 1954) and harmonica (Villa-Lobos, 1955), and for non-Western instruments such as the sitar (Shankar, 1971), all became practical, prompting another reimagining of the form.

Inter-war composers revisited the symphonie concertante (Szymanowski, 1932) and the concerto grosso (Bloch, 1925); Hindemith, Bartók, Shchedrin and Lutosławski applied concerto standards of virtuosity to the full orchestra in their concertos for orchestra. At the opposite extreme, Thomas Adès’s Concerto conciso (1997) followed the example of Berg’s Chamber Concerto (1925), placing virtuosity in a baroque-sized frame.

Contemporary concertos

Today, many solo concertos no longer go by that name – instead focusing on the music’s expressive content: James MacMillan’s Veni, Veni, Emmanuel (1992), John Adams’s Dharma at Big Sur (2003) and Kaija Saariaho’s Notes on Light (2006) are respectively for percussion, electric violin and cello. And yet something about a soloist in conversation – or competition – with an orchestra continues to grab audiences.

The concerto predates the symphony; judging from the success of works like Magnus Lindberg’s Clarinet Concerto (2002) and Mark Simpson’s Cello Concerto (2018), it might well outlive it.

Life is better with great music in it. Subscribe to Gramophone magazine today