When Julian Lloyd Webber met Yehudi Menuhin

Gramophone

Thursday, April 21, 2016

In 1980 Julian Lloyd Webber undertook a revealing and wide-ranging interview with Yehudi Menuhin that was never published, until now...

Introduction, by Julian Lloyd Webber

The following interview took place in December 1980 at Yehudi Menuhin’s house in Highgate, London. It was to be the first interview in a book I had been commissioned to write called SOLOIST that, for one reason or another, never came to fruition.

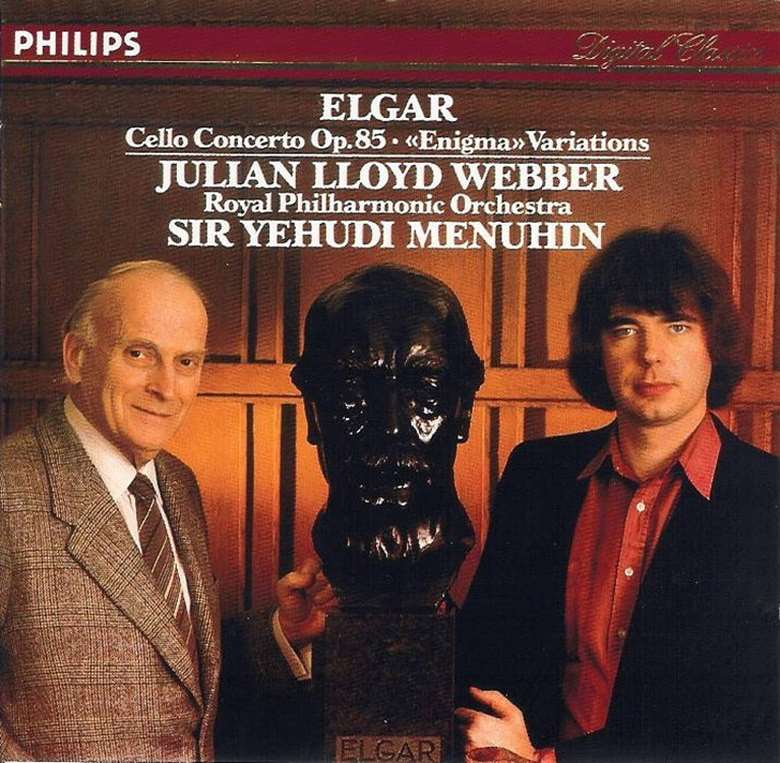

Before this interview I had never met Yehudi before. This was to change dramatically several years later when, in 1985, I recorded Elgar’s Cello Concerto with Yehudi as my conductor. Yehudi - as a very young man indeed - had recorded Elgar’s Violin Concerto conducted by the composer himself. Our recording of the Cello Concerto led to many tours and broadcasts together and to a lengthy and treasured friendship and many happy memories. This interview might have been very different had it happened 10 years later!

JLW: I would like to begin with your earliest memories.

YM: Yes. From the very beginning, performing was a natural thing because I started when I was six. I grew up with that activity just as a circus acrobat would grow up in a circus. It didn’t seem at all unnatural to me. I was never aware that I was anything unusual.

JLW: Do you still remember the first time you played with an orchestra?

YM: More or less. Don’t forget I always had the music to protect me. It’s not like someone leading a regiment into battle. You are there to play a particular masterpiece that you have studied and rehearsed and the conductor is there helping you - well, usually! You are by no means alone - it depends entirely on what your head is filled with. If it’s filled with the music and the thought that you’d want to play it and communicate it as clearly as possible, there is nothing particularly frightening about it. If, instead, you are thinking of how you appear to the audience, that this is your one and only chance, that you’ve got to make it, that there’s a critic sitting in the front row and you hope they’ll be pleased - but you yourself are uncertain because of one thing or another - then it can be sheer torture!

JLW: Do you worry at all about critics, or do you rely on your own opinion?

YM: Always on my opinion. For one thing, my parents always shielded me and never allowed me to read any criticism or articles that appeared - especially nothing complimentary! I think that was very wise because the most important thing is to keep one’s mind and heart on the job, and not be distracted. Critics’ opinions may not be irrelevant to a management, but they should be irrelevant to an artist.

JLW: Having toured all over the world and obviously had times when you weren’t completely satisfied with a performance, what is it that makes you get up the next morning and go through the whole process all over again?

YM: Simply the knowledge that you are searching for an ideal, that you have to keep trying to reach it, that sometimes you do, and that when you fail you know jolly well why you’ve failed, and you try to correct it. It’s usually quite a simple thing with someone who knows his job - it’s a matter of the right state of mind and body, a matter of sleep and work and practice, of being immersed in the music. It’s a matter of temperatures, pressures and climates - all kinds of things - and above all it’s a matter of one’s domination of all these things.

JLW: What do you feel about the tendency nowadays, on new recordings, to emphasise the performer rather than the composer?

YM: It’s not just nowadays…it goes right back to the classical period. Paganini was one of the first to make a public career of international size and Liszt did the same on the piano. But in those days the performers were the composers. Beethoven played the piano and performed his works in public, as did Mozart, Bach and César Franck. Today, of course, we see a greater specialisation and we have masses of conductors who have made their living, and a lot more, on the works of Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms. Beethoven has kept many musicians - violinists, conductors - in bread and butter. More than bread and butter, in jam too! But the composer had a relatively small part of that remuneration. Today, it’s different. The royalties that accrue are quite considerable and, certainly, if Bartók had lived a few decades longer, he’d be a rich man now. So the composer is, in some ways, better protected now. Soloists are in a category apart because their names are more well-known, but I think it’s important to place the soloist in a proper perspective. There is a commercial value, simply because a name can command big audiences, but it doesn’t mean the soloist is any more indispensable to music than a member of a fine quartet or ensemble.

JLW: What special qualities do you feel a soloist must have?

YM: He must have a certain command over himself and his audience - a certain magnetic personality which must be part of the music. But it cannot just be personality with no relation to music. And whether it’s Callas, Pavarotti or Kreisler, and whether it’s achieved by tenderness, sweetness or by command - even by defiance or by contempt - it has to be achieved by some very powerful emotion or motive.

JLW: What do you feel is the most important training for someone who wants to become a soloist? Is studying with big name teachers valid, for example?

YM: It’s most important to learn to feel the music and to project it, and it takes a particular personality to do that, to have the intensity and passion at a sufficiently high temperature to communicate, because communication is like lightning - it doesn’t happen until a sufficient electrical tension has been built up. You can’t just walk on stage and play. You have to have an intense feeling about the music you’re going to play. That’s why I think it is an advantage to be taught by a great name - if he is ready to give his time! I had Enescu. I didn’t study with someone who just wanted me to practise six hours of scales a day. That’s not enough.

JLW: What do you feel about breaking down barriers in music? You’ve already made recordings with Ravi Shankar and Stephane Grappelli…

YM: Last night I played with Oscar Peterson! My colleagues can come from wherever, provided they are really good musicians. And Peterson and Grappelli - not to mention Shankar - are the most brilliant, gifted musicians imaginable, and I’d be a fool not to give myself that stimulus and excitement. Even though I’m too old to start improvising, just to be with people who can is great!

JLW: What do you think when you encounter a slight stuffiness from critics who say that they don’t think that’s the sort of thing you ought to do?

YM: Every person is a master of their own lives. I try with the children at my school to give them a broad basis so that they’re not frightened and do not feel awkward with different kinds of music. My training was entirely classical - I started with the printed page and the written score, and it’s for that very reason that I felt so famished and so one-sided.

JLW: Do you think there is a danger at music colleges that too little emphasis is placed on other kinds of music - that it’s just the written notes?

YM: Yes! Especially as today there are so many different types of music around. From jazz to Indian to African music, there is a tremendous amount of other cultures permeating classical music today. I think, in a way, that’s salutary.

JLW: Have you ever composed yourself at all?

YM: No. It’s not my inclination. I started off as a violinist and my whole training was as a violinist. That’s why I feel that even though I made a name for myself by the time I was eleven, the children at my school of sixteen are more rounded musicians in the sense that they play more chamber music and also compose.

JLW: Probably more than any other musician, you’ve become involved in many other areas and causes. Do you think there is a danger for musicians to become too concentrated on music to the exclusion of everything else?

YM: I wouldn’t like to make any general principle. There are musicians who give all their time to everything but music! I couldn’t do that either. But to say every musician should [give] so much time to philosophy, so much time to the Red Cross, so much time to politics, I think is impossible. Every person must have his own law.

JLW: Have there ever been times where you feel that your playing has overreached itself - been better than you could ever have hoped - that you felt, perhaps, that you reached perfection?

YM: There have been moments when I felt very pleased.

JLW: And would you put that down to an outside force?

YM: No. Any outside force would have no effect unless the inside was ready and prepared. But when the two do meet, when one is prepared and there is inspiration, then that is a marvellous moment.

JLW: Obviously some conductors are easier to work with than others. Who have been your favourites to work with?

YM: In England, certainly Beecham and Boult, although I like some of the younger ones as well - Simon Rattle, Colin Davis and so on. Charles Groves, David Atherton, Vernon Handley - they’re all good - the level of English conducting is very high. There seem to be few French conductors except Paul Paray I’ve enjoyed playing with.

JLW: Has there been any particular conductor that you would single out?

YM: Yes, Furtwängler. And Bruno Walter. Those two. There are many others who are superb, but of that calibre, only Furtwängler.

JLW: Have there ever been - without mentioning names - conductors that you don’t want to work with again?

YM: Yes. Lots! Simply because I felt that either they had no ear, no rhythm, or no sympathy…or weren’t competent!

JLW: Do you feel that with a concerto the soloist obviously knows it much more intimately than the conductor?

YM: In most cases, yes.

JLW: But do you feel that it is the soloist’s prerogative to dictate a concerto performance?

YM: I think it happens automatically. The conductor usually accompanies the soloist. But - as a soloist - I must say that I welcome those moments when a conductor - if he is a conductor with something to say - contributes something himself. Then it becomes a real dialogue.

JLW: Which violinists do you especially admire?

YM: A great many. I admire the young ones coming up now - particularly Accardo and Zukerman - but I also admire great ones from the past whom I knew very well, like Kreisler.

JLW: Who was your own violin hero?

YM: Even though I never heard him play live, it would probably be Ysaÿe. I think that’s the person I feel closest to. Enesco, of course, was a great influence, and Kreisler. From a technical point of view, I admire Heifetz very much.

JLW: What sort of family background do you feel it’s important for a soloist – who lives under constant pressure – to have?

YM: Naturally, one which is as harmonious as possible! It’s difficult for a soloist to do justice to a family because music takes so much time and is generally done at home. It’s not like the businessman who works nine-to-five, and the children can always see him every evening and at weekends. It may hold to a certain extent in an orchestral player’s life - and in that respect the orchestral player is more fortunate. He can lead a good life in one place, play chamber music, then build toy trains with his children and take his wife out to the theatre once in a while! Nothing like that holds in a soloist’s life! Therefore he does need the most understanding and tolerant partner, who can help explain to the children that they are not going to see their father - or mother - as often as other children. You’ve touched upon a very difficult aspect of the soloist’s life, which requires constant travelling and erratic schedules and an absence of what people like to think of as normal family life.

JLW: Would you say you were a town person or country person?

YM: Both. I dislike the pollution in towns, the noise, the horrid traffic, and the multitudes of people who are not fulfilled who just hang about. On the other hand I love the town for its stimulus - theatres, concerts, opera, libraries and people from every walk of life. I would miss a great deal in the country, and at some times of the year it is rather forlorn. And there’s very little left now that’s as pure as the country should be. What I’d love in the country is to have my own farm!

JLW: Is that something you might have pursued if you had not dedicated yourself to music from the beginning?

YM: No, I think that if I had any talent for it, I would have done science or medicine. I would have been interested not only in the advances in medicine, but also in every kind of approach to the human body. This is something which has always interested me enormously.

JLW: Thank you so much.