Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote: a guide to the greatest recordings

Hugo Shirley

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

Strauss’s portrayal of the legendary knight errant offers brilliant dramatic opportunities for bold cellists, conductors and orchestras. Hugo Shirley surveys a recorded history reaching back nine decades

It’s one of the great feats of musical distillation and storytelling: Richard Strauss turning Cervantes’s vast two-part novel Don Quixote into a 40‑minute tone poem, or, put more accurately, a set of ‘fantastical variations on a theme of knightly character’. Composed over 14 months – Strauss wrote of having his ‘first idea’ in October 1896 and completed the score on the morning of December 29, 1897 – Don Quixote is among the most admired of Strauss’s works, a demonstration of breathtaking compositional imagination and skill, not to mention formal mastery.

It’s rightly famous for the brilliant pictorialism of the episodes from Cervantes’s novel that Strauss chose to depict: the tilting at windmills; the ‘attack’ of the sheep, represented by bleating wind and brass; run-ins with penitents and monks; the mistaking of a bumptious country girl for the idealised Dulcinea; the swirling flight through the air; the ride in a boat, from which Don Quixote and Sancho Panza emerge audibly dripping; and the thrilling final confrontation with the Knight of the Shining Moon, replete with brassy fanfares.

But the piece, as so often with Strauss, can and should be understood on multiple other levels. Key is the fact that the composer conceived Don Quixote from the start as a companion piece to his Ein Heldenleben (1897‑98); they can only be understood together, with Don Quixote undercutting the very same Romantic idea of composer-as-hero that Strauss seems to celebrate in Ein Heldenleben. And I would go on to argue that, in basing the work on a foundational text of literary modernism, Strauss was himself producing a key work of musical modernism.

In purely musical terms, certain passages are bracingly modern, too, not least the remarkable introduction, which combines the many key themes that swim confusedly around in Quixote’s mind to produce knotty counterpoint which can feel difficult to unravel – the first of many interpretative challenges for conductor and orchestra. Elsewhere, the sheer variety of textures, with instruments from opposite ends of the orchestral spectrum often yoked together, is far from easy to pull off.

The most famous choice Strauss makes in terms of instrumentation, though, is to feature prominent parts for solo cello and viola, broadly representing Don Quixote and his long-suffering squire. This results in a fascinating performance history; and although the score makes it clear that his idea was for the cello part to be taken by the orchestral principal, Strauss ignored his own advice when making his first recording in 1933, and is known to have admired the performances of the part by at least two of the star soloists featured in this survey: Gregor Piatigorsky and Paul Tortelier.

The work is often presented on disc as a vehicle primarily for the cellist, then, but heavyweight soloists (often recorded unrealistically closely) can unbalance proceedings: several draw out their solos into a series of grand, intensely serious tragi-heroic gestures – especially in Don Quixote’s Vigil (Variation V) and the moving Finale (from bar 690 to the end) – and lose the link to the work’s humour and satire. Nevertheless, Don Quixote is well served by a discography that, though by no means small – the recordings listed here represent around half the number that are commercially available – is relatively select. But the best recordings should be truly collaborative, with soloists, conductor and orchestra coming together to bring out the full brilliance and drama of the variations while achieving a compelling sense of overarching narrative.

Before we set off, though, it’s perhaps worth noting how few female cellists feature in the discography – just three. Has there historically been a reluctance to have women take on this ‘male’ role (although, of course, that hasn’t stopped innumerable male violinists representing the Hero’s Companion in Heldenleben)? Or maybe it just reflects the historic under-representation of women in the principal cello’s chair. Perhaps this will change in the future as the discography expands further.

The adventure begins

First, though, back to the past, and Don Quixote’s debut on disc, which comes from Thomas Beecham conducting the New York Philharmonic Society Orchestra with cellist (and future conductor) Alfred Wallenstein as soloist in 1932 – not reliably available now after the last Pearl reissue (4/92) was deleted. It’s a historic document, no doubt, and evidence not least of Beecham’s championship of Strauss, but for all its fluidity and musical good sense it is no match for the first recording by Richard Strauss himself. With the Staatskapelle Berlin in 1933, the composer set the benchmark for structural command, wit, imagination and even fun – in eminently decent sound. He starts off relatively swiftly but with initial tempos that are very much what we’re familiar with today. Where he differs from modern accounts is largely in unsentimentally maintaining a forward flow in the slower sections: in the Vigil, for example, or the Finale, where cellist Enrico Mainardi is noble and moving, but with none of the grandstanding and distending that later star soloists would bring.

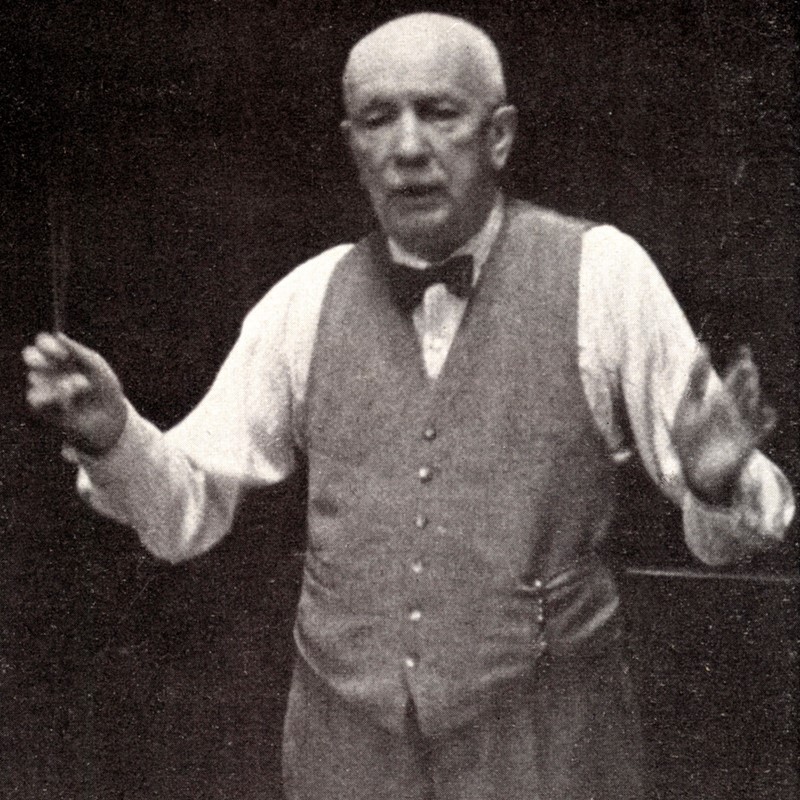

Composer as conductor: Strauss’s sense of fun shines through (photography: Bridgeman Images)

I prefer Strauss’s Berlin recording to the 1943 Munich remake with the Bavarian State Orchestra, which feels less engaged and affectionate (included in the same DG set as the Berlin account). The Munich recording is notable, though, for Philipp Haass’s transformation of the viola’s chirping diddle-diddle semiquavers (heard first just four bars into his first appearance at fig 14) into clipped acciaccaturas: a tic that would briefly find its way into some other early recordings, including Eugene Ormandy’s swift and dramatic early Philadelphia Orchestra performance, with Emanuel Feuermann as a moving soloist despite being slightly wayward in his rubato at the start of the Finale.

We hear it too in Fritz Reiner’s 1941 account with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, which features what’s surely the most lively, improvisatory conversation (at the start of Var III) of any recording, courtesy of two Russians: viola player Vladimir Bakaleinikoff and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, who, like Feuermann, gives a demonstration of how one can bring big personality to the score without upsetting the balance. Piatigorsky also stars in Charles Munch’s unpredictable but generous, moving and enjoyable Boston Symphony recording (1953), which starts off unremarkably (and slowly) before springing several surprises.

Arturo Toscanini is, perhaps predictably, something of a speed merchant: his 1953 NBC Symphony Orchestra recording clocks in at just over 39 minutes. Some moments feel a little breathless, but it’s all woven together with the surest hand. It’s just a shame that the orchestra’s principal cellist, Frank Miller, lacks poetry at times, even if the conductor does create space for him in the Finale. For Toscanini conducting a starrier cellist, turn to the live 1938 performance with Feuermann (available on Music & Arts), which, despite some rough edges, is greatly more moving.

While we’re in the US, it’s worth jumping forwards half a decade to Reiner’s second account, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This is one of a few recordings here to have achieved something like classic status – and one that certainly deserves it. Part of the partnership’s superb Strauss series on Living Stereo (I chose his Domestica as the ‘classic’ choice for that work – 12/19), Reiner’s 1959 Don Quixote mixes tenderness, brilliance and drama like few other accounts. Antonio Janigro, snapped up by the conductor while making his first US tour, is a superb cello soloist, presenting plenty of personality while at the same time integrating fully into the conductor’s vision.

Gallic dominance

By the time of Reiner’s second recording, two grands seigneurs of the French school, Pierre Fournier and Paul Tortelier – one a DG artist, the other EMI – were beginning to dominate. Let’s begin with Fournier, whose first recording, with the Vienna Philharmonic and Clemens Krauss, is surprisingly disappointing, sounding brittle and with the cellist balanced so close and playing so forcefully that he often seems to have little to do with what the rest of the orchestra is up to. Krauss’s conducting, meanwhile, is strangely lacking in imagination and affection. Fournier’s early-1960s performance with the Cleveland Orchestra and Georg Szell is much better, combining fantasy with rigorous discipline and superb playing, but is inexplicably out of the catalogue, though the most recent Sony reissue (2/98) can be found second-hand.

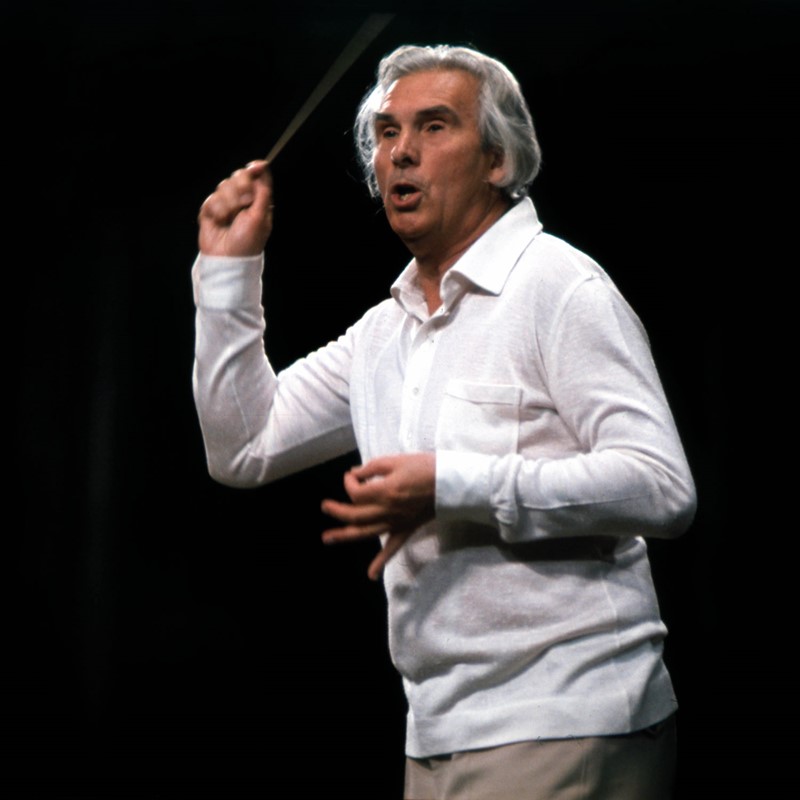

A boldly spotlit Paul Tortelier meets his match in beautifully affectionate, expertly paced conducting from Rudolf Kempe in their 1973 recording (photography: Godfrey MacDomnic/Bridgeman Images)

No such neglect for his celebrated Berlin recording, the first of three studio Don Quixotes from Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic. Big, generous and lustrous, it’s a recording whose classic status is easy to understand. Karajan’s instinctive command of the score is allied to a wonderful sonic richness from both orchestra and cellist. Few conductors relish the drama going into Quixote’s final battle so gratifyingly or convey the crushing dissonance of his defeat so grandly. But I miss humility in Fournier’s playing, whose Vigil comes close to sounding like a big concerto and whose Finale, though nicely flowing, is projected too confidently.

For Tortelier’s first official recording, in 1947, he joined the RPO and Thomas Beecham; but, though the conductor had by then long experience in the work, there’s a sense of his having to tread carefully with an orchestra less familiar with the tricky score. No such issue with the cellist’s recording with Rudolf Kempe and the Staatskapelle Dresden (the best-known of three he made with the conductor, the others coming from Berlin and Munich). Kempe’s conducting is a marvel, full of wit, character and drama, and there are plenty of wonderful things in Tortelier’s generous, long-lined playing, too. It’s a glorious embarras de richesses, no doubt, but one could quibble that, as with Fournier and Karajan, the Finale is hardly sehr ruhig as Strauss marks, with the cellist’s playing remaining robustly healthy even when Quixote should be quietly slipping away. And while viola player Max Rostal – spotlit, like Tortelier, in the balance – plays with brilliant vividness, he also gives Sancho Panza an inappropriate heroism.

More big guns

I find Karajan’s 1970s recording with Mstislav Rostropovich (EMI/Warner, 6/76), for all the glories of the cellist’s playing and the richness of orchestral palette, somewhat generalised in its grandeur – and it seems, in any case, to be currently available only physically and not digitally. Rostropovich’s live 1964 recording with Kirill Kondrashin and the Moscow Philharmonic strikes me, despite occasional gruffness from the cellist, as more dramatically imaginative and engaging, with a surprisingly understated Vigil and a gloriously heartfelt Finale. That’s what we get, too, from a recording, caught by chance when an engineer pressed ‘record’ during a unscheduled run-through, from Jacqueline du Pré and the New Philharmonia under Adrian Boult. The performance has an understandable off-the-cuff feel but du Pré’s playing, unapologetically big and intense, is all the more moving for it – an unforgettable document in its own right.

Rudolf Kempe (photography: Godfrey MacDomnic/Bridgeman Images)

Jumping forwards to the digital era, Yo‑Yo Ma’s Boston Symphony Orchestra performance, conducted by Seiji Ozawa, finds the great cellist wheeling out everything in his expressive arsenal to break the 45-minute mark in a performance that seeks the sublime but arguably teeters over into the ridiculous. It’s slower even than Mischa Maisky’s indulgent Berlin Philharmonic account from 2002 (DG, 4/04), with a distinctly sedentary Zubin Mehta on the podium and Tabea Zimmermann as a starry viola soloist. Steven Isserlis seems to strive for better integration in his two recordings: there’s a lot to like in the relaxed, intelligent and detailed account he made with Edo de Waart and the Minnesota Orchestra, which is preferable to the later recording with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, somewhat indulgently and eccentrically conducted by Lorin Maazel (Sony, 9/01).

There’s a certain indulgence in Karajan’s final Berlin recording, too, but it’s allied to an overwhelming affection and warmth for the work in a performance that still shows the old magician conjuring up plenty of drama alongside the lyrical expansiveness. And, in Antonio Meneses, he has a solo cellist of a new generation who seeks integration and moving interiority in a Finale that, like the best, seems to flow directly out of what’s come before. There’s a similarly intelligent performance from Raphael Wallfisch in Neeme Järvi’s beautifully integrated if somewhat washily recorded 1988 Chandos account with the Scottish National Orchestra (1/89).

Unexceptional 1980s performances from Vladimir Ashkenazy and the Cleveland Orchestra (Decca, 12/86) and Kurt Masur and the Gewandhausorchester (Philips, 7/91) are uncompetitive, despite fine solo work from Lynn Harrell and Heinrich Schiff respectively. Harrell’s later live performance with Gerard Schwarz and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, however, offers something remarkable: an interpretation from both cellist and conductor that’s big, dramatic and irresistibly alive, not to mention hugely refreshing. More recent cello soloists have included Jan Vogler, returning to the Staatskapelle Dresden (where he began his career as principal cellist) to take centre stage in an elegant performance under Fabio Luisi, superbly played by the great Strauss orchestra, if not as sharply characterised as it might be.

Classy German cellists have dominated the catalogue since, too, including Maximilian Hornung with a civilised Bernard Haitink and the BRSO (Sony), Daniel Müller-Schott with Andrew Davis in Melbourne (Orfeo, A/19) and Isang Enders with Sebastian Weigle and the Frankfurt Museum Orchestra (Oehms, 10/18), the ensemble Strauss himself conducted in the work’s second performance. The best of that particular crop, though, comes from the orchestra that gave the premiere, the Gürzenich-Orchester Köln, in a boldly modern and tautly argued recording conducted by Markus Stenz. And it features not one star soloist but two (both somewhat more closely recorded than ideal): cellist Alban Gerhardt alongside the luxury Sancho Panza of Lawrence Power.

Away from Germany, Paavo Järvi conducts a characteristically intelligent and musical account with the NHK Symphony Orchestra, with Truls Mørk as an urbane and sensitive soloist, which offers much to enjoy while lacking that last ounce of drama and affection. Closely miked recordings from Kian Soltani and the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, live under Daniel Barenboim in his second recording (available to download on Peral, 1/20), and Ophélie Gaillard and the pedestrian Czech National Symphony Orchestra under Julien Masmondet are worth mentioning for the sake of completion, but neither is competitive.

Back to first principals

Let’s now return to the other strand of the performance tradition, recordings featuring orchestral principals, which we left way back with Toscanini in 1953. Toscanini’s example was followed in Ormandy’s second Philadelphia recording from 1961 (Sony), Lorin Maazel’s 1968 account with the Vienna Philharmonic (1/69 – briefly reissued on Australian Eloquence, 12/14), Leonard Bernstein in New York in 1970 and Zubin Mehta in LA in 1973. The Ormandy has many fine things, Bernstein offers plenty of character and Maazel has his moments; Mehta’s ragged performance, though, should be given a wide berth.

Jump forwards to 1991 and Daniel Barenboim’s Chicago Symphony recording (12/91) has no such technical issues but simply suggests, like his later recording, that it’s not a score he has much affinity for. André Previn’s 1990 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic is a very different matter (Telarc, 10/91). It’s swift, superbly dramatic and beautifully played, with Franz Bartolomey a moving cello soloist, but apparently, alas, not widely available at the time of writing.

More recently, François‑Xavier Roth’s conducting of the now-disbanded SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg and its excellent if somewhat reticent principal cello, Frank‑Michael Guthmann, is unsentimental and clear-headed, the orchestral sound stunningly detailed. There’s similar clarity in Vasily Petrenko’s excellent Oslo Philharmonic recording, with Louisa Tuck a supremely eloquent cello soloist. I welcomed it warmly on its release in 2019 but, in the context of this survey, it now occasionally feels a little careful, sacrificing drama to accuracy.

I have no such issues with David Zinman’s 2003 recording with the superb Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, which allies the clarity of those two recent competitors to a superb sense of drama and vivid pictorialism, tracing a compelling line via the differently sharply characterised episodes through to a titanic final battle, a grandly dissonant return home and one of the most moving Finales on record. Cellist Thomas Grossenbacher offers an exemplary demonstration of well-integrated solo work throughout, complemented by the excellent Thomas Rouilly on viola. It’s an account that presents a middle way between some of the more extreme approaches I’ve outlined but, rather than feeling like a compromise, is suffused with its own burning conviction and compelling sense of rightness.

I hope it says more about the quality of Zinman and his orchestra – and of their Strauss survey, released to little fanfare on the super-budget Arte Nova label – than about my own lack of imagination that I declare them my top choice now for Don Quixote as well as for Symphonia domestica. Similarly, in my other recommendations, I find myself returning to Reiner and his Chicagoans for my classic choice, not to mention giving Strauss himself once again the historic crown. Finally, despite my reservations about big‑name, big‑personality Quixotes, I had to find room for Kempe’s Dresden recording. All four are, in their different ways, for me the most unmissable accounts of this brilliant work.

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today