Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony: A deep dive into the best recordings

David Gutman

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Artistic salvation or forced rejoicing? David Gutman investigates Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, his ‘make or break’ response to ‘just criticism’ and the varied recordings it has inspired

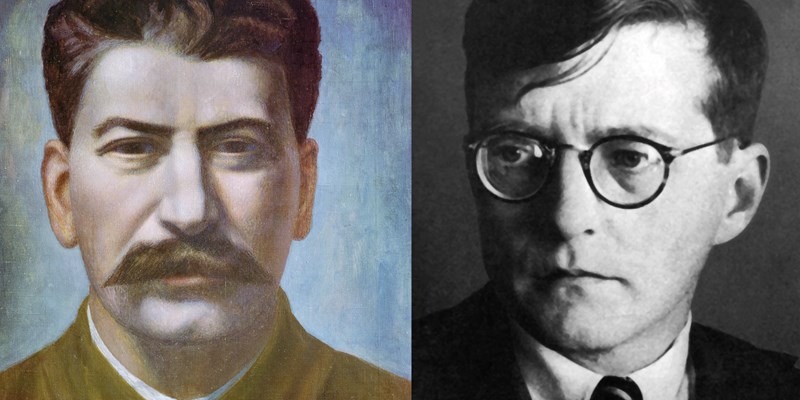

The young composer and the Leader and Teacher: Stalin is depicted (left) in a 1936 portrait by avant-garde artist Pavel Filonov (photo: Bridgeman Images)

Have we somehow been duped by what composer and Shostakovich sceptic Robin Holloway calls the ‘battleship grey … factory-functionality [of] music without inner necessity’? From its very first performances, given at the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, Shostakovich’s D minor Symphony has seldom failed to co-opt an audience (but for what?). Tagged (but by whom?) ‘a Soviet artist’s creative reply to just criticism’, it is both the most popular and the most mysterious of 20th-century symphonies. The arguments have had 80 years to play out in the world’s concert halls and recording studios.

Everyone agrees that the Fifth was make or break for Shostakovich, the piece in which he squares the circle, writing music of integrity and emotional intelligence while effectively remaking himself as composer laureate of a totalitarian state. In January 1936, after Stalin attended a performance of Shostakovich’s dangerously erotic opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, there appeared the notorious Pravda editorial ‘Chaos Instead of Music’, with its threat that things could ‘end badly’ for Soviet musicians – and for Shostakovich in particular. Its unnamed author was David Zaslavsky, a well-connected Soviet journalist and propagandist. No family was left untouched by the purges. The composer’s uncle, sister, brother-in-law and mother-in-law were arrested and when his patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky, was declared an ‘enemy of the people’, it is likely that he himself was interrogated by the NKVD. The musicologist Nikolay Zhilayev, to whom Shostakovich played the second movement in May 1937, had joined the disappeared by the time of the Fifth’s Leningrad premiere on November 21, 1937.

Yevgeny Mravinsky, with Shostakovich in Leningrad in 1965 (photo: Itar-Tass News Agency / Alamy)

Not every story about these terrible years bears scrutiny but for the composer few options remained. Compelled to engage with contemporary problems from a Utopian perspective that regarded defects as positive forces pushing society towards a socialist goal, he managed to cast himself as the Soviets’ ‘optimistic tragedian’. Yet while the Fifth might still be read as the progress of an intellectual from a state of individualistic error to a nirvana of self-transcendent solidarity with the masses, that is not what it means to us today. Nor, in all probability, would it have been so interpreted by his own audience. The first performance was entrusted to Yevgeny Mravinsky, a political ingénu near the beginning of his long relationship with the Leningrad Philharmonic. Such was the work’s success that the state record label authorised a first recording. (An oddity of the symphony’s current discography is that neither Mravinsky nor his Soviet-Russian successors are especially well represented.) His sometime colleague Kurt Sanderling was at the first Moscow performance on January 29, 1938, and remembers that ‘after the first movement we looked round rather nervously, wondering whether we might be arrested after the concert’. After the third movement, many wept openly. That said, the extent to which such music embodies an anguished debate with a regime that dispensed both the highest awards and the deepest humiliations may matter less than how well it works as absolute music in the great tradition. Michael Tilson Thomas notes the composer’s reluctance to add potentially compromising expression marks to his score and makes valid points about its deference to symphonic archetypes handed down by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Mahler. The music is Beethovenian not least in the sense that it reflects and refracts the values of those seeking to interpret it. ‘Why is it that we need answers and explanations from Shostakovich all the time?’ asks Bernard Haitink. ‘This is great music and his reasons lie in the music.’

Toning down the dissonance

Although the Fifth is a more conservative, less colourful symphony than its immediate predecessor, suppressed until the high noon of Khrushchev’s Thaw, its idiom is foreshadowed in the Cello Sonata (1934). It may be that like many a left-leaning contemporary in the West, Shostakovich was simplifying his musical language because he wanted to, reverting to a more orthodox four-part model, toning down the dissonance. The first movement of the Fifth is easy to follow if by no means merely simple. Indeed, the angular contour of its main material rang alarm bells with sympathetic colleagues anxious to secure the composer’s rehabilitation. These accented gestures can be rendered as stark calls to attention or phrased with less insistence in a way that leads the ear on. Karel Ančerl suggests both aspiration and constraint by having the violins articulate their up‑beat rhythms more snappily than the lower strings, only later underselling the second subject’s easeful balm with his breezy tempo. Should we discern thwarted amour in the line’s allusion to the Habanera from Bizet’s Carmen and its anxious iteration by exposed violas? Was Shostakovich encrypting a reference to Roman Karmen, a Soviet photographer, filmmaker and rival in love? The development process brutalises these ideas into a malevolent march, peaking with a climactic resolution in the home key, the determined unison declamation of first-group material manna to the rhetorically inclined maestro. The icy, contemplative coda offers no consolation and for the conductor a rather different test of sensibility.

The Allegretto can be more or less heavy-footed. Arriving like a Mahlerian Ländler and exiting with a Beethovenian gag, its ‘ironic’ Trio wanders into the path of the oncoming coda and is squashed flat. The high point is the Largo that so moved contemporary audiences. Certainly the finest music Shostakovich had composed up to that time, it moves from serene detachment to the kind of emotional outpouring otherwise effectively proscribed by the Terror. There are echoes of traditional Russian Orthodox chant as Shostakovich divides his violins into three and both violas and cellos into two sections. Recordings need to convey this rich and varied texture but also the special magic of strings playing really quietly. The very slow basic tempo adopted by a handful of conductors on either side of the Iron Curtain conveys an extra dimension, whether of truth or beauty. Leopold Stokowski may have begun the practice of breaking in on the morendo fade-out.

Brass instruments, silent throughout the slow movement, return with a vengeance in a finale long excoriated by Western highbrows where the paint-stripping timbre of 20th-century Russian orchestras adds menace. Few performances nowadays would aim to evoke the euphoria of a successful party congress. Even if we doubt the evidence of Testimony, the composer’s much-disputed ‘memoir’, it is apparent that Shostakovich had other ideas. Seemingly by design, the music recalls the song ‘Rebirth’ (‘Vozrozhdeniye’), the first of Four Pushkin Romances, Op 46 (1936‑37). This is obvious from fig 120 in the movement’s elegiac central episode, less so in the swaggering march theme which may represent the ‘barbarian-painter’ who ignorantly daubs over a masterpiece: in time the pigment will flake away to reveal the truth of the original inspiration. Artur Rodzinski takes the scissors to the score in all three of his recordings as if embarrassed by the harp-flecked glimpse of redemption.

The very end of the work, after so many obsessively repeated As on high violins, is surely neither submissive nor jubilant. It is worth pointing out that regardless of the tempo chosen for the coda (the printed indications vary wildly – crotchet=188 or quaver=184 – depending on the edition used) there is no explicit request for the now traditional further ritardando as timpani and bass drum drive home the final unison. The ‘business of rejoicing’ already sounds forced in Tchaikovsky’s Fifth. What Shostakovich encodes is the determination to survive. Or perhaps something more Beckettian: ‘… you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.’ Kurt Sanderling keeps a lid on any hint of celebration by omitting the final cymbal clash. Daringly, Mark Wigglesworth adopts the faster tempo, a consistent crotchet=160 throughout these final 35 bars conveying overt brutality his own way, implacably and with no rit at all.

The Fifth abroad

Notwithstanding a British premiere conducted by a committed communist, Alan Bush in April 1940, the Fifth’s wider dissemination was not governed by political considerations. The first US broadcast had aired two years previously with Rodzinski directing for NBC. Stokowski felt no comparable compulsion to trim the finale, finding a quite different sensuality in the writing without loss of ‘blaze’, even applying portamento. Gramophone’s review of his early Philadelphia set (HMV, 9/42) discusses the music rather than the playing. Many of its observations re the finale – ‘Not, I think, a very good movement’ – voice familiar qualms. Shostakovich ‘seems to be working too hard’. Assorted relays from later in Stokowski’s career include one documenting his return to concert-giving at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music in 1960. The low‑fi sound cannot disguise the incendiary, unpredictable nature of the performance and that supercharged freely bowed string tone.

The German premiere was delayed until 1946, Sergiu Celibidache directing the Berlin Philharmonic. By the end of his life the Romanian maverick was conducting it more slowly than anyone else, which may explain the absence of a posthumous official release from EMI. Leonard Bernstein’s famously histrionic take turns out to have been pretty much in line with the virtuoso mainstream, only more flexible. His deliberate opening best reflects Shostakovich’s directions. Only one section of the finale finds him more precipitate than István Kertész, supervising an accident-prone Suisse Romande Orchestra in higher-fi. Aficionados can eavesdrop on Bernstein’s 1959 sessions (‘Leonard Bernstein: Historic Broadcasts, 1946-1961’ on West Hill Radio Archives).

Back to the USSR

What some find lacking there is the higher seriousness rightly or wrongly associated with the Russians. Mravinsky’s 1954 taping, leaner and tauter, was not picked up for UK distribution until much later. Currently more accessible is a dress rehearsal-cum-concert performance staged for Soviet TV in the summer of 1973. Wearing an open-necked white shirt and wielding a baton, Mravinsky is less interested in dramatising individual incidents than in building great arcs of ferocious intensity. Colours are bleached figuratively and literally, the dynamic range compressed. Kirill Kondrashin (HMV, 12/85), speedier and a better fit for the Mahlerian jocularity of the second movement, can be raw in every sense, though he corrects the textual variant in Mravinsky’s finale two bars before fig 127. It was the international export of Maxim Shostakovich’s USSR Symphony Orchestra LP (HMV, 5/71) – ahead of more venerable rivals – that revealed the feasibility of an effortful denouement within the Soviet performance tradition. Maxim’s subsequent renderings from London and Prague (Supraphon, 1/98) display a slow-motion stoicism that risks morphing into dullness for all that there are metronome markings to justify it. The line of state-sponsored Soviet-Russians ends with Gennady Rozhdestvensky (Olympia, 5/89), for whom sensitivity, realism and melodrama collide, the Fourth Symphony not so distant after all.

Great orchestras

While non-Russians had different priorities, to claim that we know ‘better’ now is the kind of arrogant posturing for which Shostakovich himself had no time. An∂erl knew what it was to survive the camps – Hitler’s, not Stalin’s. Can we really censure the mellifluous flow and nuancing of his vintage Czech Philharmonic as in some way beside the point? Melodrama and self-indulgence were alien to his nature. Documentary evidence suggests that Shostakovich really did enjoy Bernstein’s rapid finale and he had no problem with Sanderling’s decision to start the movement at a comparable lick. The composer wanted the interpreter to decide. There are two recordings apiece from André Previn and Eugene Ormandy. The soft sheen of the LSO strings as captured by Decca’s James Lock is key to the appeal of the then Hollywood outsider’s RCA LP version. If the players’ professionalism deserves much of the credit, Previn is more patient than customary in 1965 and finds a certain profundity in transmuting the Largo’s raw apprehensions. The finale bolts joyously for home as it usually did in pre-Testimony days. Ormandy maintains the Philadelphians’ distinctive sonority only to overstep the mark with (what sounds like) a glockenspiel tinkling away during the finale’s insistent As.

Whether achieved by the meticulous marking up of score and parts or a balder literalism, Paavo Berglund (HMV, 3/76) and Bernard Haitink offer something else again. The latter’s dark-hued studio recording, a Gramophone Award-winner, proved particularly influential, adding Brahmsian richness to available options. Was its release greeted with such reverence because it followed hard on the heels of the publication of the supposed ‘memoir’? Possibly. Haitink’s ‘hands off’ approach remains an earnest attempt to make structural sense of the music’s grand symphonic aspirations and he has a truly great orchestra.

Mix-and-match moderns

The coincidental advent of digital recording with the realignment of Shostakovich’s image in the West produced a boom in recordings worldwide, impossible to chronicle in full. As late as 1992 Evgeny Svetlanov sticks to a Soviet ideal, promoting a bullish positivism that transcends matters of tempo. Valery Gergiev, another patriot, has various options in contention including a superior audiovisual account filmed in Paris with his own echt Russian band. While his fluttery semaphore elicits a decent response (the toothpick comes and goes), this is not quite the incendiary music-making of old.

The most durable trend has been for mix-and-match projects in which maestros from the old Soviet bloc front more or less prestigious Western ensembles. Mstislav Rostropovich chose to reset the dial most radically, rewriting some phrasing in the Scherzo and throughout insisting on a ‘dissident’ recasting that obliges Shostakovich’s musical argument to proceed by fits and starts. His heroic big-scale music-making was perhaps best experienced live. Kurt Masur (LPO, 7/05) follows suit, not only favouring a maximally ‘revisionist’ coda but allowing the long lead-in to grind to a halt – agonising or revelatory? Rudolf Barshai is of broadly similar mind, only neater. Averse to extremes, Vladimir Ashkenazy’s serviceable RPO is outshone by the RSNO for Neeme Järvi, or so it seems in Chandos’s more distanced, larger-than-life sound. Mariss Jansons is predictably persuasive in several stabs at the piece, the Mravinsky legacy most evident in his all-round skill as orchestral conjurer. As part of his peripatetic 10-disc cycle, Jansons gave the Fifth more space in Vienna, the Philharmonic’s luscious string sound deployed more purposefully than by Silvestri (HMV, 9/62) or Solti (Decca, 10/94). Jansons’s obvious successor is Andris Nelsons, among the last of the conductors with experience of the fading Soviet empire and its intensive training. You’ll need to forgive DG’s penny-dreadful strapline, ‘Under Stalin’s Shadow’. His Boston Symphony play superbly, albeit with a certain geniality and gloss.

Kurt Sanderling with Shostakovich (photo: Konzerthaus Berlin Archiv)

A handful of conductors wring exceptional results from less prestigious ensembles, projecting an element of vulnerability or isolation. As aware as Maxim Shostakovich that the initial metronome mark (quaver=76) implies a singularly funereal Moderato, Mark Wigglesworth and Vasily Petrenko are more successful in maintaining the listener’s interest. The former’s BBC NOW never chortles where it needs to snap, though some hear the extremes of dynamic (partly attributable to BIS’s production style) as over the top and the conducting as lacking in humour. If Wigglesworth is doing a Rostropovich here, pulling out interpretative stops to communicate a ‘message’, the execution is subtler. The first-movement coda is unforgettably icy, the upward glissando to fig 46 observed with forensic clarity. (Stokowski made much of it too in his fleshier way.) And at the very end of the symphony no rendition more convincingly conveys the frightening unanimity of a drilled crowd. Petrenko’s view feels less radical, which may make the results easier to live with. The unglamorised sound mostly strikes a balance between clarity and spaciousness with an almost gritty quality to the string-playing. The ‘negative’ denouement feels more than usually plausible. More recently, Manfred Honeck divided opinion with an altogether brighter, energetically articulated reading, superlatively recorded. And still they come, most similarly labelled ‘live’. We’ve had the first rendition from a Chinese ensemble, Long Yu’s Shanghai Symphony Orchestra (Accentus, 8/19), a text-driven roller coaster from Krzysztof Urban´ski and the NDR Elbphilharmonie (Alpha, A/18), the level-headedness of Gianandrea Noseda in London and sobriety from Mark Elder in Manchester, plus an intelligent coupling, the Pushkin Romances.

A non-Russian was also on the podium in the late 1940s when the Fifth became the first major Shostakovich work permitted public performance in the USSR during Stalin’s second cultural clampdown, the post-war campaign against ‘formalism’. Kurt Sanderling was never to record a comprehensive Shostakovich symphony cycle (unlike at least one of his conducting sons) but there’s no mistaking the pedigree. Conductor and composer hit it off initially in wartime Siberia, Sanderling having fled east from Hitler’s Germany. Had he been able to take up Rodzinski’s offer of a US post, it’s harder to imagine those two seeing eye to eye: Sanderling’s Largo is three minutes longer than Rodzinski’s. His own studio-made Fifth filters authenticity of experience through thoughtful old-school German training and the benign acoustic of East Berlin’s Christuskirche. Nothing flashy or artificial gets in the way.

The Top Choice

Berlin SO / Kurt Sanderling (1982)

Berlin Classics

This thoughtful account from behind the Iron Curtain will best suit listeners who find rival versions (or perhaps even the music itself) prone to overstatement. Sanderling incorporates traits associated with different performance traditions before bringing down the curtain in patently oppositional mode. It all sounds ‘symphonic’ even so and the slow movement is as moving as any.

This article originally appeared in the November 2021 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today