Contemporary composer – Gerald Barry

Paul Griffiths

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

The angular, brazen and fiercely individual music of this true Irishman undergoes colourful analysis by Paul Griffiths

In moments of exhilaration one may find one’s mouth falling open, not knowing whether to laugh or scream. So it could be when listening to the music of Gerald Barry. There are holes in the harmony, and though the line keeps on going, it jumps and kicks and jolts through constantly changing patterns, sometimes picking up more or less familiar tunes and throwing them away again, while the overall sound may be of instruments lashed together against their natural inclinations, or pushed into tight corners registrally, or exposed – to their own and everyone’s embarrassment. Barry’s music is at once highly formal and iconoclastic, perky and suave, sensuous and brittle. Wit and intensive persistence are key features – wit, but not the elegant ironies of former times, which have hotted up and taken a twist. This is Stravinsky squared, cubism cubed.

‘Why so wild?’ one might be tempted to ask, while certainly not wishing it otherwise. Perhaps there is some explanation in Barry’s origins – in the west of Ireland, which, musically speaking, is close to nowhere. Ireland has produced great numbers of writers, fighters and saints, but not so many composers. There’s a proto-Romantic pianist (John Field), a theatre man (Michael Balfe) and a late Romantic (Charles Villiers Stanford), all of whom left Ireland when young to find their opportunities elsewhere – these miscreants do not offer much of a tradition, certainly not for a composer with a strong sense of the past, a composer whose output includes more than one explicit if precarious homage to Beethoven, as well as a work entitled The Ring (for choir, wind band and bells) and two operas whose heads are spinning with Handel.

Barry’s student years coincided pretty much with the 1970s, when not only minimalism was fresh and energetic but also older music, as it started to take on new life in the hands of performers striving for period style. The young Barry took it all in. After studying at University College Dublin, he followed the usual Irish route – out. For almost 10 years he was on a grand tour of continental cities, continuing his education along the way with Peter Schat, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Friedrich Cerha and, for the longest period, Mauricio Kagel, another tricky outsider. But then, unlike his compatriot predecessors, he returned to Dublin, and soon his music was making a mark, both there and in London.

Among the works that first brought him attention, the enigmatically titled ‘————’ (1979) is immediately characteristic: a snakes-and-ladders board of scales ominously rising only to start again at other levels, music at once plain and peculiar, always doubled – shadowed – by an ensemble of clarinets, strings and keyboards (harpsichord doubling piano). There is a nod to – or perhaps more a glare at – the past in the fact that one starting point, according to the composer, ‘was the idea of capturing and freezing the scales used as flourishes in Tchaikovsky’s symphonies’. In its sound and manner, however, in its refined unrefinement, the piece is fully Barryesque.

Its composer spent most of the next decade nested back in Dublin working on his first opera, The Intelligence Park, set in the city in 1753, at the time of a musical glory that was not to be sustained. (This was close to the time that Handel’s Messiah was brought to birth there.) With a libretto by Vincent Deane that supplied the composer with ideal material – sophisticated and curt, fancy-filled and rudely direct, deep with ambiguity – the opera considers issues of power and impotence, sexual, social and creative, its principal characters being a composer, his male lover, a castrato singer and a young woman, who, the object of others’ desires and designs, has some of her own. Flashes from the imaginary composer’s opera are included in a score which, with elegant coarseness and bizarre cool, splices together mid-18th-century and modern musical worlds.

While working on The Intelligence Park, for which he had neither commission nor obvious prospect of performance, Barry produced a few other things, including Triorchic Blues, a tussle of typically angular rhythmic forces originally enshrined in the piano (1990), with versions later following for other instruments. (Triorchidism might have given some basis for Casanova’s gossip that Giusto Tenducci, sometimes called ‘Il Senesino’, a castrato who not only visited Dublin but married there, and whom Barry and Deane took as the model for their castrato, Serafino, succeeded in fathering two children.) After the first performance of The Intelligence Park, at the Almeida Theatre in north London in 1990, came a pepped-up creativity that quickly brought a second opera, again with Handelian echoes: The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit (1991-2), written for Channel 4 TV.

The ironies of being an Irish artist promoted in the former imperial capital by no means escaped this alert composer. To a commission from the BBC for the 1988 Proms he composed Chevaux-de-frise, a fearsome orchestral barrage of noisy dissonances going at a quick march or jogtrot, in emulation of the eponymous spiked barriers formerly used on battlefields. Another BBC commission resulted in The Conquest of Ireland (1995) for baritone and orchestra, to a text by the composer’s namesake, the medieval Welsh writer Gerald de Barry (Giraldus Cambrensis), and for the 15th anniversary of the Royal Festival Hall he came up with a brazen recasting of the national anthem, God Save the Queen (2001).

Following almost a decade largely filled with orchestral and chamber music, he returned to opera to set a play (also filmed) by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, about a passionate woman in midlife and her failing, stunted or unpursued relationships with her younger lover, her daughter and her secretary. The all-female cast is buffeted by a wind-heavy orchestra whose harmony is as negligent as the society in which these women have to live. Asked about that aspect of his music for the work, Barry answered: ‘I would say every single bar in this opera can be related to a key centre.’ However: ‘Sometimes I had to agonise a lot to find out what the centre actually was.’ His characters live in a musical world whose tonality is cracked, besmirched, degraded, ambiguous – a world open to the expression of uncertainty and irresolution. The premiere was a concert performance in Dublin in 2005, followed soon after by a staging by English National Opera.

Since then Barry has been working on operas almost continuously, beginning with La plus forte (2007), setting a monodrama by August Strindberg for Barbara Hannigan, who had sung the daughter in the London production of The Bitter Tears. Hannigan was also his chosen Cecily for The Importance of Being Earnest, which, again, had its premiere in a concert performance (Los Angeles, 2011), and has since been staged in Nancy and London. Next will be an opera drawn from Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. Meanwhile, other genres have not been neglected, recent works including a full-scale Piano Concerto (2012) as well as an array of smaller vocal and chamber pieces.

It is a bewilderingly diverse output, and fiercely individual, perhaps not least in its aim. Asked last year what he wanted listeners to take away from his music, Barry answered in one word: ‘Joy.’

Recommended recordings

‘————’. Piano Quartet No 1. Triorchic Blues and other small-scale pieces

Noriko Kawai pf Nua Nós / Dáirine Ní Mheadhra

(NMC)

These little pieces from roughly the time of The Intelligence Park are full of fun and games, with the bonus of booklet-notes by the opera’s librettist, Vincent Deane. Gramophone Review

Of Queens’ Gardens. Chevaux-de-frise and other orchestral pieces

National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland / Robert Houlihan

(Marco Polo)

Some of The Intelligence Park is here in Of Queens’ Gardens, and Chevaux-de-frise is a classic, plus the disc includes a couple of delightful ballet moments. Gramophone review

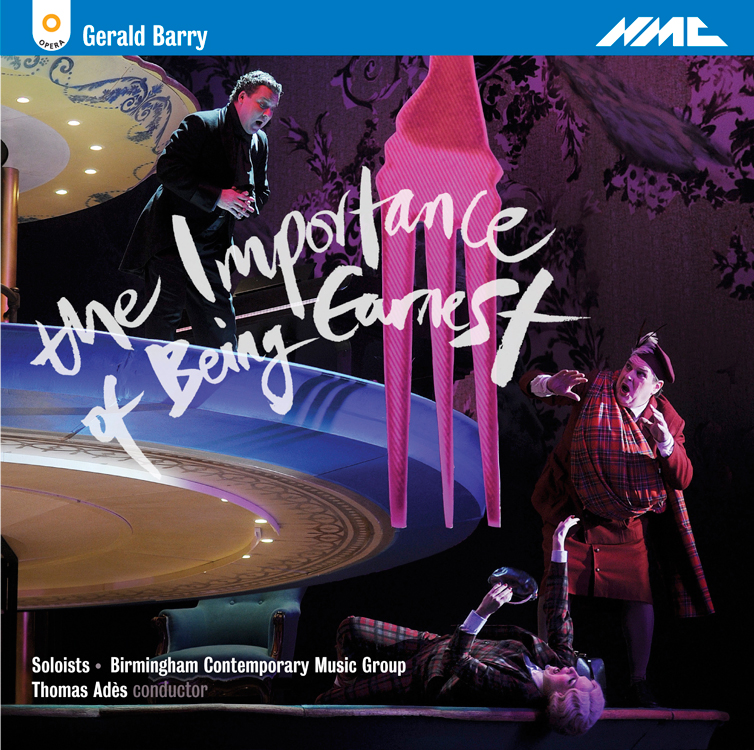

The Importance of Being Earnest

Soloists incl Barbara Hannigansop Peter Tantsits ten Birmingham Contemporary Music Group / Thomas Adès

(NMC)

Wilde’s comedy happily seizes a whole other level of wonder, wit and strangeness. Gramophone review

This article originally appeared in the December 2014 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe