Contemporary composer: Thomas Adès

Pwyll ap Siôn

Monday, March 20, 2017

Vanishing spirals, time, entrapment and reference: Pwyll ap Siôn explores what characterises this British composer’s works

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the premiere of Thomas Adès’s Asyla for large orchestra, whose dynamic synthesis of primal power, rhythmic intensity, melodic invention and lyrical subtlety prompted many to hail it as a contemporary classic and latter-day Rite of Spring, with which it shares a certain Dionysian abandon.

While Asyla remains Adès’s most well-known and widely performed work – having within 10 years of its premiere received more than a hundred performances – it is worth pausing momentarily to retrace the steps that led the composer to this extraordinary piece, and the direction his music has taken since then.

A gifted pianist and talented composer, Adès studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama as a junior student before reading music at King’s College, Cambridge, where his teachers included Alexander Goehr and Robin Holloway. In different ways, both left their mark on Adès’s early works: Goehr in terms of instilling a sense of formal control and methodological rigour, and Holloway in allowing past historical models, idioms and allusions to filter through into his music.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Adès’s early compositions – many of which were written while he was still a Cambridge undergraduate – is an inherent fluency that appears to have emerged naturally from a creative wellspring that had fully absorbed, mastered and reinterpreted the then-current techniques and practices of contemporary music. However, Adès was already developing his own voice, for example in the Chamber Symphony (1990). On one level, the work displays several textbook modernist traits, such as complex multilayering, polyrhythmic patterns and processes, the use of extended techniques, extreme instrumental registers and an emphasis on both individual dexterity and ensemble virtuosity. But it is also multilayered in its musical reference and historical resonances, fragments of quotes bubbling underneath before being propelled to the surface by magnetic forces latent in the musical material itself.

Many subsequent works leading up to the composer’s first opera, Powder Her Face (1995), grappled with similar issues, from the inventive and dazzlingly colourful Living Toys (1993) for chamber ensemble to the more introspective Arcadiana (1994) for string quartet. The latter’s sixth movement, ‘O Albion’, represents something of a departure, being the first to allude more or less explicitly to a past historical model (in this case, Elgar) to evoke a sense of lost innocence and nostalgia. In its direct tonal style and serene simplicity, ‘O Albion’ was in its own way as stubbornly radical as the complex, uncompromising Living Toys.

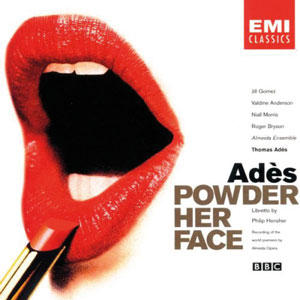

Complex or simple, modern or postmodern, hermetically sealed or replete with cultural significations, Adès’s music has often navigated a course between these polarities, resulting at times in a rich synergetic alchemy. One of his most immediately compelling and powerful works is the two-act Powder Her Face – a vivid and visceral portrayal of the colourful and celebrated life of Margaret Campbell, the Duchess of Argyll. Adès’s borrowing of references and allusions expose the lurid, subversive and sensationalist aspects of the duchess’s life. The opera pillages from all manner of forms and styles, including a Carlos Gardel tango and other popular dance forms, 1930s light song and the repertoire associated with the Palm Court Orchestra, Jack Buchanan, Paul Anka, 1950s pop songs, Walton’s Façade, Berg’s Lulu, Janáček and Stravinsky, all of which prompted Harrison Birtwistle to observe that Adès can’t make a musical move without relating to something historically: ‘Nearly everything relates to something else, a model.’ At the same time, a parallel process informed by the music’s own internal models is set out in Adès’s opera: a grizzly double-edged paradox places the duchess as both architect and victim of her own downfall. The music’s inherent logic serves to deepen the Duchess’s sense of desperation as the world she once possessed is squandered away by excesses of various kinds.

Adès has described Powder Her Face as an opera about a woman who finally becomes entrapped in ‘a world of perfume and fantasy and memory’. Entrapment also informs his other two operatic works, both of which mark different periods in the composer’s development. The Tempest (2003), his three-act opera based on Shakespeare’s play, sees its shipwrecked characters trapped on an island controlled by Prospero’s magic. The Exterminating Angel (2015), also in three acts and based on Luis Buñuel’s surrealist film, is set at a dinner party that never ends, where characters drift from one inescapable situation to another.

Adès’s operas are in a sense ‘summative’, building on technical puzzles and challenges explored in previous works, while the orchestral pieces are catalytic, providing opportunities for the composer to strike out in new directions, initiating new phases.

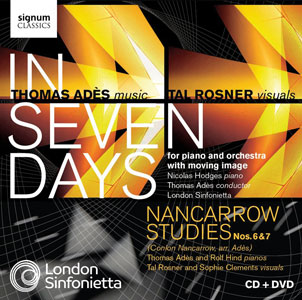

The Exterminating Angel is ostensibly about time standing still and, by extension, the end of time. Shaping time in music has, of course, preoccupied composers throughout history, but it’s a theme that especially concerns Adès. Asyla addresses the notion of being trapped in time, as heard most forcibly in the pulsing third movement, ‘Ecstasio’, the composer’s paean to electronic dance music of the mid-1990s. Polaris (2010) for orchestra engages with a kind of cosmic time, while In Seven Days (2008) is about time contracting and expanding.

Adès achieves this never-ending notion of suspended time not so much through rhythmic or metric means (although he has increasingly employed stasis and repetition in more recent works), but by a spiralling succession of staircase-like harmonic wedges in fourths and fifths. These patterns are heard in an almost endless series of variations and transformations at the beginning of many works (and often at the end, too, in a process that takes the music full circle), looping around in ever-endless motion towards a tonal horizon that is rarely fully achieved. Paul Driver has suggested that these vanishing spirals have their origins in Bartók’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle, though Ligeti’s second piano étude, Cordes à vide, with its expanding and contracting motion, may also have served as a reference point.

Already heard at the beginning of Arcadiana, this temporal trope becomes the central idea in many later compositions, including the Violin Concerto (Concentric Paths, 2005), where it forms the subject of a dialectical struggle between soloist and orchestra, and Tevot (2007) for orchestra, where it becomes part of a symphonic argument that, in the end, generates an infinite entropy of vanishing spirals.

Underpinning his use of such spiral harmonies is Adès’s belief that notes are pushed and pulled around by magnetic forces that attract or repel. When a note is struck, a whole nexus of possibilities comes into play. The role of the composer is to explore some of these relationships. As Adès notes: ‘The impulse comes first, the method second.’ The subversive force contained within each note to disobey and rebel has compelled Adès to evolve an ‘irrational’ harmonic logic that, in a work such as America: A Prophecy (1999) for mezzo and large orchestra, forces the listener to stare into the dystopian abyss and aftermath of Judgement Day – and to face, head-on, the destruction of time itself.

Recommended recordings

Powder Her Face

Soloists; Almeida Ensemble / Thomas Adès

EMI Classics (9/98)

This captivating work brings together all the elements of Adès’s early style. It’s everything music theatre should be: witty, flamboyant and sardonically funny while also providing moments of serious reflection, consideration and identification. This opera is a must-hear as well as a must-see.

In Seven Days

Nicolas Hodges pf London Sinfonietta / Thomas Adès

Signum Classics (5/12)

This is a vivid, programmatic piano concerto in which Adès explores extremes of simplicity and complexity. It is impeccably performed on this recording, which includes a DVD with visuals by Tal Rosner.

Asyla. Tevot. Polaris

LSO / Thomas Adès

LSO Live

This includes the heavyweight symphonic works Asyla, Tevot and Polaris, each approaching the orchestral medium from a new angle and demonstrating Adès’s mastery of the form.

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

Adès facts

Born

London, March 1, 1971.

Piano prize

He won second prize in the piano category of the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition in 1989.

Composition studies

Alexander Goehr and Robin Holloway were his teachers at the University of Cambridge (1989-92).

Directorships

He was the first music director of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, 1998-2000, and served as artistic director of the Aldeburgh Festival, 1999-2008.

Best-known piece

Asyla (1997), which won the Grawemeyer Award in 2000.