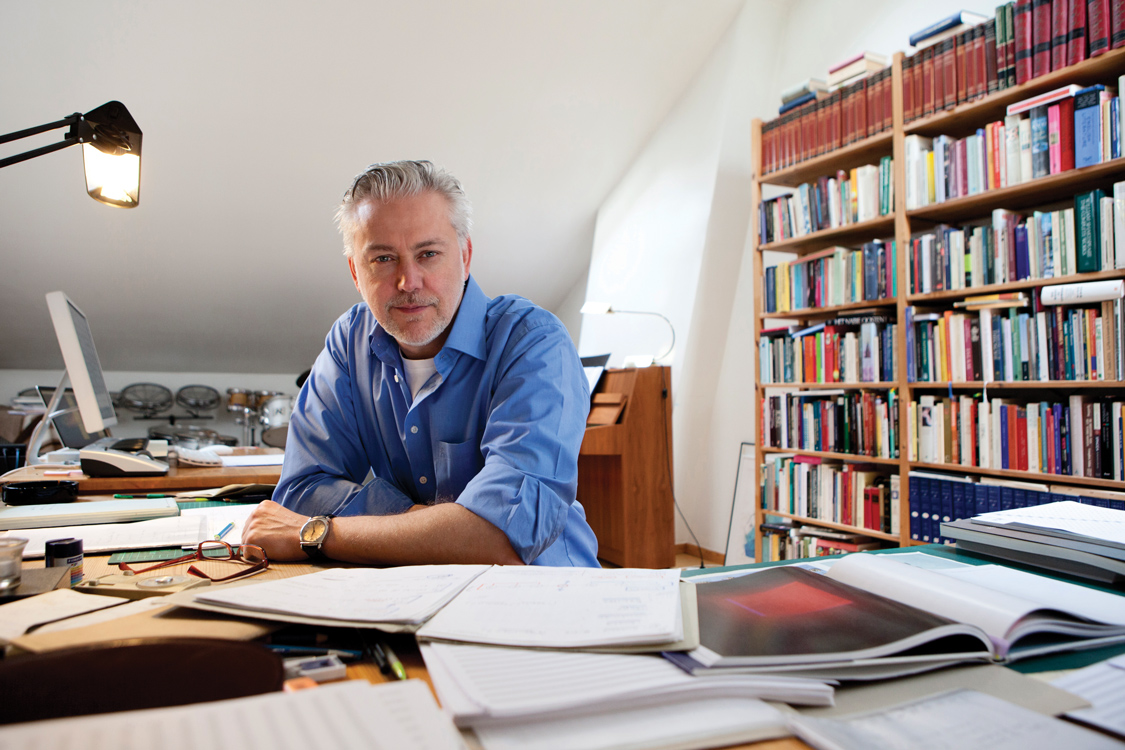

Contemporary Composer: Wim Henderickx

Pwyll ap Siôn

Wednesday, January 6, 2016

Here is a composer who tackles big subjects on the largest of canvases, drawing inspiration from around the world, writes Pwyll ap Siôn

Large-scale cycles of compositions inspired by oriental philosophy and spirituality, works that relate to the cosmos and the universe, titles taken from Sanskrit words, and a style that casts its net far beyond Western musical traditions and practices – one might think of words such as ‘eclectic’, ‘diverse’ or ‘postmodern’ to describe Wim Henderickx’s music.

In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Despite its wide range of references, Henderickx’s music is hardly eclectic in nature, rarely plays the quotations game, is seldom ‘stylistically heterogeneous’, and certainly does not suggest a composer of postmodern proclivities. On the contrary, this process of creative osmosis has shaped Henderickx’s music into a clearly identifiable and internally consistent musical organism – as if he has stood back and viewed the world from a great distance, studied its many cultural forms and practices in detail, immersed himself fully in its musical styles and traditions, then carried on much as before.

Born in Lier, Belgium, in 1962, Henderickx started off as a jazz and rock drummer. This led to an interest in percussion, which he pursued as a student at the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp. Western and non-Western percussion instruments have continued to engage the composer ever since, and often form the cornerstone of his orchestral output. Raga I, for example, composed in 1996, is effectively a concerto for percussion and orchestra. Its two-part, slow-fast structure is loosely based on the North Indian bandish (or gat). The work builds up to a dramatic climax via disjunct melodic lines on tuned percussion (glockenspiel and timpani) during Part One, followed by an onslaught of untuned percussion instruments (including bongos, temple blocks, roto-toms and octobans) in Part Two. Groove! (2010) is another work which dynamically confronts percussive and orchestral forces.

After a period away from orchestral writing in order to focus on music theatre, Henderickx returned to the orchestra with Tejas (2009). Its powerful opening evokes, in the composer’s words, ‘a kind of primordial big bang that provides the energy for the rest of the composition’. Textures simulate large sound masses floating in enormous spaces, and passages vividly evoke the Earth’s presence and its cosmic vibrations. Tejas remains one of his most powerful, ambitious and impressive works: a veritable ‘Rite of Spring’ for the 21st century.

Despite its symphonic dimensions, Tejas is very much a concerto for orchestra. However, soon after completing it the composer set to work on a symphonic cycle. The first of a projected set of three (of which only one has been written so far), the five-movement Symphony No 1 was premiered in 2012. More programmatic than Tejas, its subtitle, At the Edge of the World, is from a sculpture by Anish Kapoor. Recordings with the Royal Flemish Philharmonic under Edo de Waart and Martyn Brabbins of Henderickx’s Symphony No 1, along with Groove! and the oboe concerto Empty I, plus Empty Mind I for oboe, orchestra and electronics, will be out next year.

Henderickx’s main inspiration often emerges from non-Western sources. Tejas forms the sixth part of the ambitious Tantric Cycle. In seven parts, and drawing on Eastern philosophy and Buddhism, it took six years to complete and would take several hours to perform in its entirety (the cycle has yet to receive a complete performance). Each section is self-contained, however, and ranges from pieces for smaller forces to the 70-minute music theatre work Void (Sunyata) (2006-7).

Other works in the cycle include Nada Brahma (Sanskrit for ‘God is sound’), which is scored for soprano, instrumental ensemble and electronics. Meditative, reflective and atmospheric in tone and expression, Nada Brahma represents a different side to Henderickx’s musical character. Its seven movements engage with issues relating to time, energy, sound, spirituality and silence. A vocal line intones an imaginary text created by the composer, while a part for electronics created in collaboration with composer and sound artist Jorrit Tamminga adds a subtle sonic layer. The work is dedicated to British composer Jonathan Harvey (1939-2012), with whose music Henderickx shares a particular affinity.

Henderickx’s chamber music regularly draws on an array of oriental percussion (Tibetan cymbals and Chinese opera gongs, for example), appropriates ritual gestures, employs microtonal elements and adopts ornamental lines that are reminiscent of Japanese calligraphy – all of which clearly suggests the influence of the East. His fondness for polyrhythmic layering comes from studies of African music, heard most clearly in the groove-based Confrontations (2003) for African and Western percussion. His sense of form and geometry relates to Indian art, while his use of elaborate ornamental lines has evolved out of working with musicians from the Middle East. After his exposure to Middle Eastern music, grace notes became an essential feature of his work, especially in the chamber music. In particular, Disappearing in Light (2008) for mezzo-soprano, viola, alto flute and percussion foregrounds the composer’s concerns with counterpoint and linearity, which then forms a close relationship with time – what Henderickx has described as ‘the relationship between the macro and the micro’.

However, it would be misleading to view these non-Western references as some kind of latter-day chinoiserie or a reactionary orientalism. As Henderickx states: ‘I’ve always maintained that I’m a Western composer but with a real fascination for [non-Western] ideas. The Tantric Cycle really came about through my intense fascination with these philosophical ideas, but is also connected with ideas about time and form. Time has a linear identification but it also has a circular identification. Maybe I haven’t found a solution to this dichotomy yet – I’m still searching for new ways in which to do it.’

In fact such elements are integrated within a largely European set of musical practices and principles. Like many European composers of his generation, Henderickx spent time studying sonology in IRCAM in Paris and attended the composition classes at Darmstadt. The influence of electronic and spectral music is especially evident in the granular-like textures of early works such as Le visioni di paura (1990) for orchestra but can also be heard more recently in the fourth movement of the First Symphony. Although never a central preoccupation, electronic music has remained an interest for the composer, sometimes forming an essential part of the process, as in his recent Oboe Concerto (2014) or as an additional soundscape in The Four Elements (2011) for mezzo-soprano, flute, violin, clarinet, cello and optional electronics.

Henderickx’s preoccupation with European forms such as the symphony and concerto also extends to opera and music theatre. His work in the latter has often developed in tandem with a long and fruitful association with Antwerp-based company Music Theatre Transparent. Henderickx’s only opera, Triumph of Spirit Over Matter (1996-99) does not address the cosmic narratives of his large-scale works but traces the story of a struggling painter.

At the centre of his work is therefore a concern with the human condition and its struggle to make sense of the world and the universe beyond. It’s a concern that motivates Henderickx to set out his ideas on large musical canvases. In a recent interview he summed this up as follows: ‘I love big monuments. The late Gerard Mortier, director of La Monnaie and director of the Salzburg Festival, once said, “Man has to build cathedrals again”. This idea of trying to make something “important” in the proper sense of the word is what I really like. That’s why I write a big symphony or a large choir piece for hundreds of singers. I feel connected with these big monuments.’

Recommended Recordings

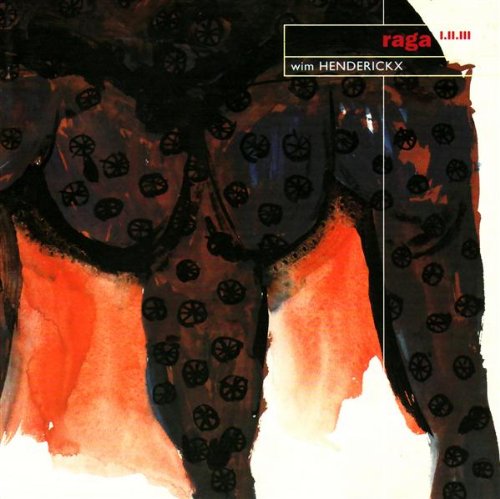

Raga I.II.III

Leo De Neve va Gert François perc Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of Flanders / Grant Llewellyn

(Megadisc Classics)

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of Flanders under Grant Llewellyn produce punchy, propulsive performances of Henderickx’s trilogy of Indian-inspired works, with memorable contributions from percussionist Gert François and viola player Leo De Neve.

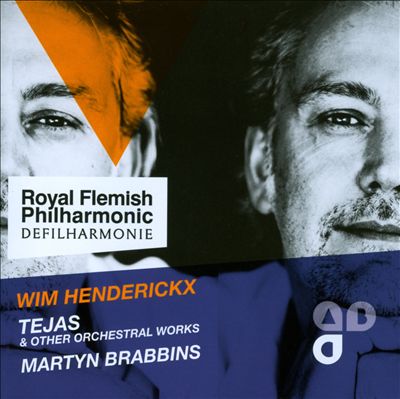

Tejas & other orchestral works

Royal Flemish Philharmonic / Martyn Brabbins

(Cutting Edge)

This disc offers a fascinating overview of Henderickx’s orchestral oeuvre, spanning more than 20 years. Martyn Brabbins and the Royal Flemish Philharmonic pull out all the stops in an explosive performance of Henderickx’s Tejas, which remains one of the composer’s most impressive works.

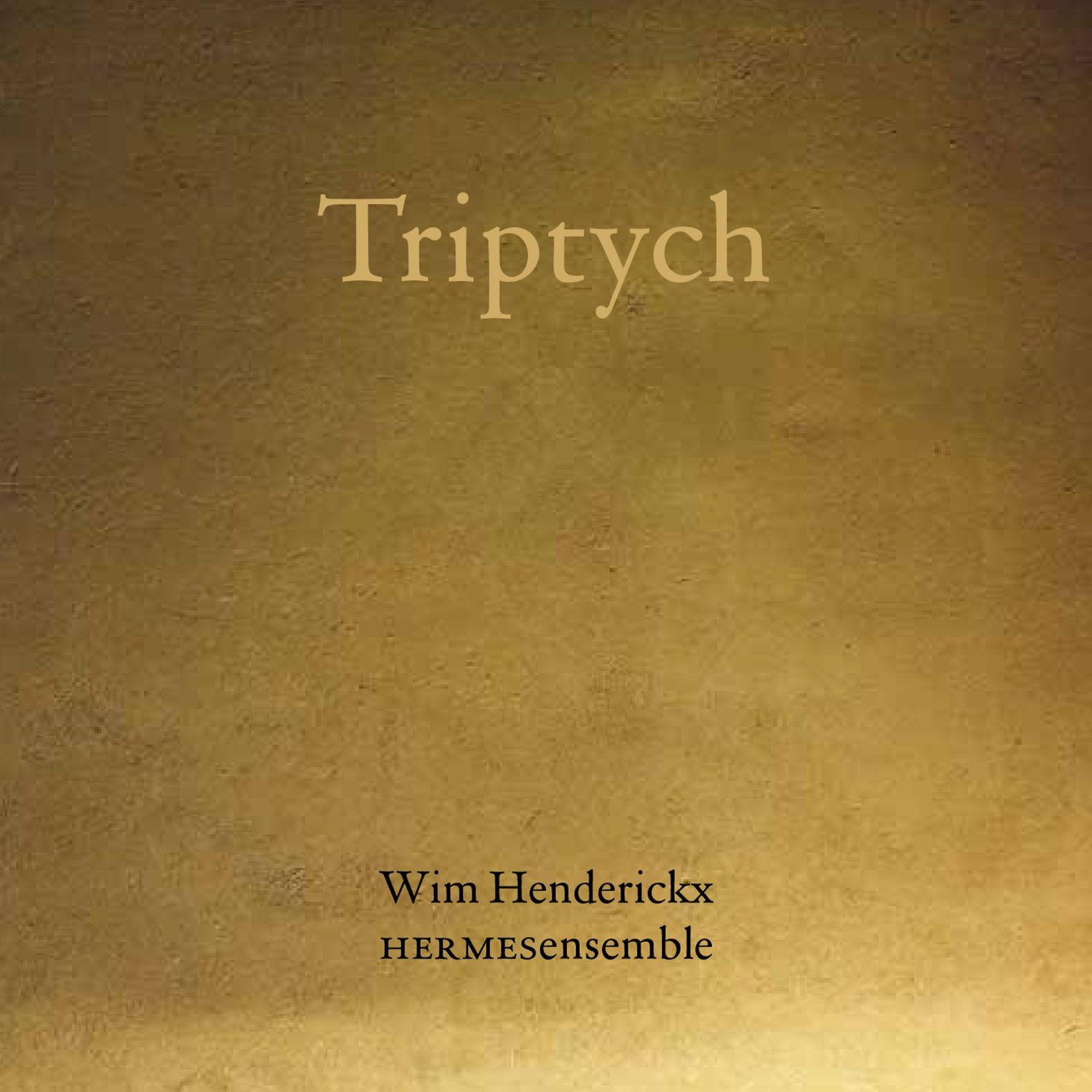

Triptych

Hermes Ensemble / Wim Henderickx

(Hermes Ensemble)

Hermes Ensemble’s unrivalled understanding of Henderickx’s chamber music is confirmed yet again on this excellent recording, out this month, which features two recent works by the composer, On the Road and Atlantic Wall. Initially released as a limited edition, Triptych is now available worldwide via Launch Music International.