Strauss's Alpine Symphony: which recording to own?

Hugo Shirley

Friday, January 12, 2018

Hugo Shirley finds recordings that best convey the sense that something greater is at stake than the notes on the page in this symphony-cum-tone poem exploring humanity and nature

The position of Eine Alpensinfonie in Richard Strauss’s oeuvre – indeed, in any music history more generally – has always been problematic. Completed in 1915, it sits at the heart of a decade in which Strauss, comfortably ensconced in his Salome-funded villa in Garmisch, was seen to have lost his position at the forefront of the musical world. For many, it represented a last gasp of a lost age of excess; a final essay in a genre – the tone poem – that was rooted in the previous century, produced by a composer who made a speciality of mismatching vast means to meagre ends.

The means are, admittedly, vast: a dozen offstage horns (although Strauss sanctions their parts being covered in the orchestra) as part of a beefy brass contingent, a minimum of 18 first violins and a well-stocked percussion section bolstered by wind machine, thunder machine and cowbells. The specified two harps, the composer adds blithely, should be ‘doubled where possible’. The score even suggests the wind players make use of a recently invented device, Bernhard Samuels’s Aerophon, to help them with their long legato lines.

But what, exactly, were the ends Strauss had in mind? Ever since the premiere, conducted by Strauss with the Dresden Hofkapelle in Berlin on October 28, 1915, the work seems widely to have been interpreted as straightforwardly pictorial. The composer’s 22 descriptive headings in the score (a day’s trajectory, charting a mountain walk and taking in a variety of Alpine sights) certainly encouraged such a view, and in 1917 the American writer Henry T Finck suggested that ‘The Alpensymphonie [sic], like its predecessors, presents no complicated riddles to the interpreter’.

But what of the score’s second half, where purely descriptive titles – such as ‘Gewitter und Sturm, Abstieg’ (‘Thunderstorm and Tempest, Descent’) and ‘Sonnenuntergang’ (‘Sunset’) – start to mix with more enigmatic headings: ‘Vision’, ‘Elegie’ and ‘Ausklang’ (the musical term for ‘conclusion’, but also implying more generally the waning, dying away of a sound or sounds)? Finck decided this represented ‘a decided anticlimax. The teutonic mania for length comes into play, and the work is made to last forty-five minutes, when twenty-five would have been better.’

For many Straussians, though, the work’s final sections are anything but an anticlimax: this is where its deeper meaning manifests itself. Research traces Eine Alpensinfonie’s gestation back to the 19th century, taking in Strauss’s personal recollections as well as reactions to the tragic lives (and deaths) of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the painter Karl Stauffer (an obscure figure today). It was the death of Mahler in 1911, however, that finally inspired Strauss to start addressing the work in earnest: ‘I intend to call my Alpine Symphony “Anti-Christ”,’ he wrote in a diary entry that surely offers the key. ‘Since it involves moral purification through one’s own effort, liberation through work and the adoration of eternal, glorious nature.’

Symphony or tone poem?

Part of the confusion regarding the work stems from its title: adherents insist on its symphonic stature, doubters dismiss it as a ‘musical Baedeker’ – a mere sonic guidebook to the Alpine sights. But surely it should be possible for it to be both, and any performance should find a balance that positions the descriptive details within a coherent broader musical argument. In the best performances, moreover, the piece also seems to be a meditation on the history of the tone poem itself. In its earlier stages, we hear what can be achieved technically in the genre (‘At last I have learnt to orchestrate,’ Strauss is reported to have said at the final rehearsal); in the later stages, the composer, delving ever deeper, shows what the genre, at its best, should achieve.

The earliest recording comes from as far back as 1925: a businesslike affair from Oskar Fried and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Music & Arts). But it’s Richard Strauss’s own recording made with the Bavarian State Orchestra in Munich in 1941 that sets a benchmark for striking the work’s essential balance. This might at first also seem rather businesslike and efficient, a case of Strauss keeping calm and carrying on in what was a disastrous, humiliating year for him. It is one of the fastest in this survey, too, at a little over 45 minutes – never lingering, avoiding the ritardandos between sections that would later become standard practice. Nevertheless, it has an unmistakable gravitas, and a real sense of the work’s drama as well as easy, natural coherence. Technical matters are a bit rough and ready, admittedly, but the sound is excellent for the time.

Eine Alpensinfonie’s history on disc in the 1950s is perhaps defined as much by who didn’t record it as by who did. It was not included in the series recorded by Strauss’s great friend Clemens Krauss with the Vienna Philharmonic for Decca, nor did it feature in the influential Strauss recordings made by Fritz Reiner in Chicago – one wonders how its early fortunes might have been different if it had. Instead, the decade represents something of a ragbag. Carl Schuricht’s scratchily played, scratchily recorded 1955 account with the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra (Hännsler Classic), for example, has the speed of Strauss’s own account but little of the tenderness and care. I’d steer clear, too, of Franz Konwitschny’s live 1952 Bavarian State Opera Orchestra account (Nixa/Urania), variously available, which is even more of an ordeal.

Karl Böhm’s two 1950s versions are much better: characteristically clear-sighted, sensible accounts, which immediately push the total time of the work to the now more standard 50-minute mark. The first, from 1952, clocks in at over 54 minutes, but never feels indulgent. And while it might feature a rather ragged RIAS Symphony Orchestra – with an especially wild principal trumpet – it has impressive intensity: listen to the powerful build-up he achieves at the end of the ‘Vision’ section. Böhm’s rather matter-of-fact 1957 Deutsche Grammophon account with the Staatskapelle Dresden feels a tad dutiful in comparison.

Perhaps the most remarkable account of the 1950s comes from that other great Strauss orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic. Although currently available only to download (via Presto Classical) and to stream (on various platforms), Hans Knappertsbusch’s recording from 1952 is grand and all-encompassing and looks deep into the relationship of man to nature. Listen to the striving, improvisatory ardour of the violin lines in ‘Sonnenuntergang’, or the oboe solo at the summit (‘Auf dem Gipfel’), capturing a moving sense of awestruck vulnerability and humanity. The sound is passable, but the performance remains compelling. There’s another compelling performance, too, from Dimitri Mitropoulos and the same orchestra, recorded in 1956 (Urania – download only). This account has much the same sense of sweep and grandeur – if somewhat unrelentingly, given its swiftness – but is technically a great deal rougher.

The age of the LP

The next recording also follows a grandly symphonic path, but comes from a somewhat unexpected source: Soviet Russia, with Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. It’s a brooding, often broad account, as one hears right from the first patient build-up to the ‘Sonnenaufgang’ (‘Sunrise’) – a picture painted in generous sweeping strokes, with some marvellously characterful, tangy playing. It’s not always (as on the glacier – ‘Auf dem Gletscher’) fully under control, but it’s unfailingly exciting.

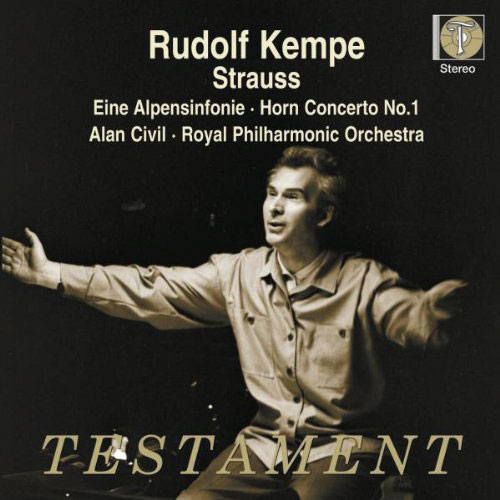

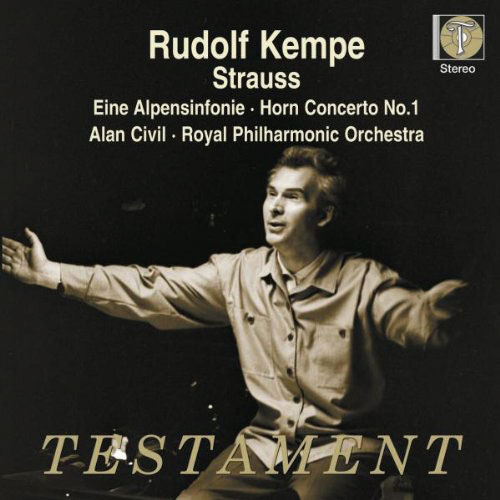

My next recording from the 1960s, though conducted by Dresden-born Rudolf Kempe, also comes from beyond the Straussian heartlands. In the first of his two recordings of the work, he draws fabulously exciting, fearless playing from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; the bold, burly brass are on especially boisterous, outdoorsy form. The whole orchestra gives its all – the strings tire a little, especially in ‘Vision’ – in what is also ultimately a moving account, in sound (originally released by RCA, but now scrubbed up on Testament) that is gloriously fresh and direct.

Kempe’s next recording, set down five years later as part of his complete Strauss survey with the Staatskapelle Dresden, is as mellow and urbane as the RPO performance is direct and exciting, supremely musical and with every phrase beautifully turned. By contrast, Sir Georg Solti’s 1979 performance with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra sounds unforgivably unloving, brash and rushed (Decca, 9/80). Zubin Mehta’s first account takes us across the Atlantic, with plenty to enjoy from the playing of the Los Angeles Philharmonic (Decca , 4/76), not least in a luminous rendering of the final pages. But elsewhere here, as well as in his rather rotund 1989 account with the Berlin Philharmonic (Sony, 8/90), there’s a distinct lack of tension and excitement.

Digital Era

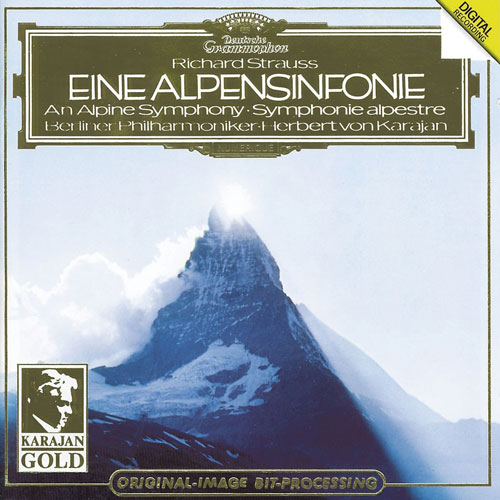

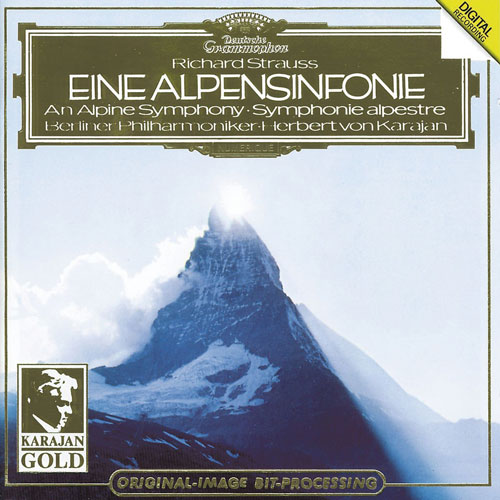

We’re getting ahead of ourselves, though, for nearly a decade earlier it’s the Berlin Philharmonic, sounding like a completely different orchestra, that ushers in the digital era. The age of the CD sees recordings start arriving at an average rate of at least one a year, a proliferation that is impossible to cover comprehensively in this survey; but Herbert von Karajan’s 1980 Deutsche Grammophon recording still stands as a majestic peak. Though of course fabulously played, if not always totally flawlessly, it’s an account that offers a great deal more than a mere showcase of snazzy new technology – indeed, the sound, toned down in subsequent remasterings, was worryingly bright in early incarnations.

Karajan brings to the score a compelling symphonic coherence, a broad, generous lyricism and an almost Brucknerian sense of line. He never loses track of its trajectory, even through the early sightseeing (he has his hunting horns, incidentally, playing from the orchestra rather than offstage). But he also manages to create a deep sense of humanity’s relationship to the vast, majestic forces of nature. His account of the final pages – where Strauss at one point asks for the winds to play ‘in sanfte Ekstase’ (in soft ecstasy) – achieves a magnificent golden intensity.

It’s a hard act to follow, and the next two recordings, from Sir Andrew Davis and the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Sony, 2/83) and André Previn and the Philadelphia Orchestra (EMI, 12/83), can hardly compete – Sony’s sound for Davis’s dutiful account, in particular, is disappointingly muddy. But Bernard Haitink’s 1985 Philips recording with another of Europe’s great orchestras, the Concertgebouw, offered a serious challenge. Unfailingly musical, played with fabulous warmth, and again with an impressive coherence as well as patience, this release stood for a while as a joint benchmark, but it seems today to lack that last ounce of excitement, of the sense that something greater – beyond the notes on the page – is at stake.

Likewise Herbert Blomstedt’s San Francisco Symphony account from 1988: technically superb, and much praised on its release, it nevertheless fails now to reach the heights. Nor do Neeme Järvi’s solid SNO account from 1986 (Chandos, 12/87), Vladimir Ashkenazy’s slightly flabby 1988 performance with the Cleveland Orchestra (Decca, 12/89) and Edo de Waart’s with the Minnesota Orchestra in 1989 (Virgin, 8/90) really compete these days, despite the last’s eloquent way with the all-important final sections of the work.

Staying with US recordings, I should add that it’s not a score with which Daniel Barenboim seems at home in his 1993 Chicago Symphony Orchestra account (Teldec, 6/93), a little generalised and with the brass, in particular, seeming reluctant to work as a team. Jump forward 15 years, and Marek Janowski’s with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (2008) is notable for a storm of rare precision, but marred by some raw playing from the brass (Pentatone, 11/09).

Closer to home

To return to the heart of Europe is to return to brass playing of a more mellow, blended sort, and certainly that is one of the great pleasures of Horst Stein’s urbane 1988 account with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra. There’s a lovely transparency to this recording (originally released on Eurodisc, but now available on DG’s commemorative Bamberg SO box-set), as well as a seductive sheen to the strings, even if Stein’s approach ultimately falls short in intensity. Kurt Masur and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra present the score well enough (1992, Philips – nla), but without much sense of exhilaration – special mention should be made of the vividly thundering timps, though.

Previn and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1989 (Telarc, 9/90) too often feel pedestrian, and Seiji Ozawa’s 1996 Philips recording with the same orchestra (10/97) only hits its stride in the second half. In Dresden in 1993 we find Giuseppe Sinopoli pushing the Staatskapelle to extremes, with the brass on warm, majestic if slightly wobbly form. This is an interesting but eccentric account: broad passages are stretched out, the final minutes almost to breaking point, while some of the wind playing is rather undercharacterised.

We’re on slightly safer ground back with the Bavarian RSO with another controversial maestro, but one with a fine Straussian record: Lorin Maazel. His vivid 1998 account is extremely well recorded and, on the whole, fabulously well played. There’s a great deal of excitement, including a thrilling storm, but it’s also a performance that drifts in and out of focus a little, and is not without its eccentricities.

Two recordings from a little further east, both featuring the Czech Philharmonic, can be skated over: there’s little reason to seek out Zden∆k Koler’s sluggish Supraphon account, recorded live in 1994 (12/95); and Ashkenazy’s 1999 Ondine remake (A/01) is sensibly musical but still short on tension and, on occasion, accuracy.

The new millennium

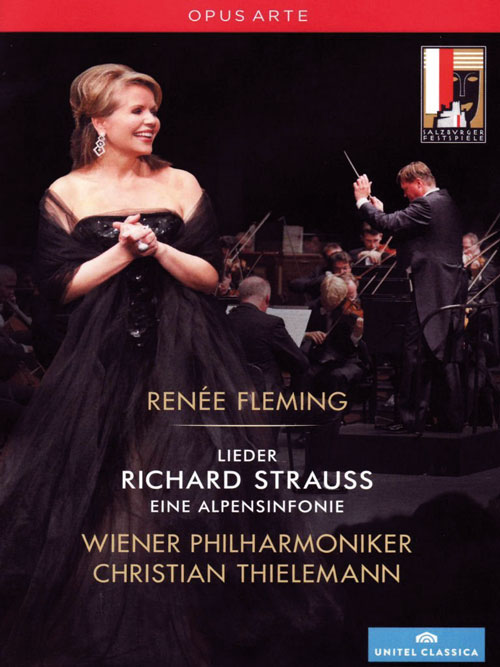

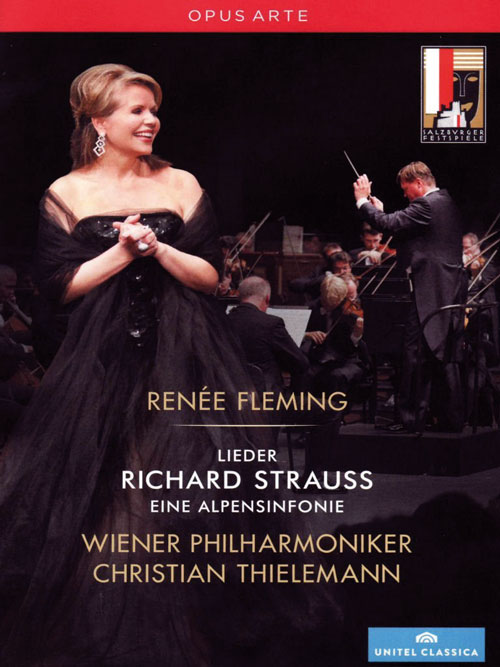

Twenty years after Karajan’s recording, Christian Thielemann enters the fray as a new representative of the old-guard approach, with a recording for DG in the tradition of Karajan and Knappertsbusch. Grandly expressive, flexible and Wagnerian in scale and scope, his live Vienna account does, however, occasionally flirt with portentousness. His approach is better heard – as well as seen – in two later DVDs: from Dresden (with the Staatskapelle) in 2014 on C Major and, especially, from Salzburg in 2011, where grandeur, lyrical generosity, intensity and sheer sonic splendour are better balanced within a compelling symphonic framework – and where the Vienna Philharmonic violins excel themselves in particular.

In a 2005 recording, Antoni Wit and the Staatskapelle Weimar on Naxos (9/06) present a fine, moving achievement, but must concede on technical terms to some of the competition. David Zinman’s technically unimpeachable 2002 account with the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra (Arte Nova, 2/03) ultimately lacks excitement, as does Fabio Luisi’s handsome, burnished 2007 one with the Staatskapelle Dresden (Sony, 4/08). But Semyon Bychkov with the WDR Symphony Orchestra is well worth seeking out as offering one of the most cogently argued ‘symphonic’ accounts, the work presented as a seamless arc, with the final stages supremely expressive.

There’s a similar cogency to a reading by Sebastian Weigle – another distinguished Straussian in both orchestral and operatic works. His excellent live 2015 recording with his Frankfurt Opera and Museum Orchestra is a marvel of lyrical expansiveness and generosity, with the conductor exerting a masterful grip over the work’s second half in particular (and listen out for the big-hearted horn solo in ‘Ausklang’).

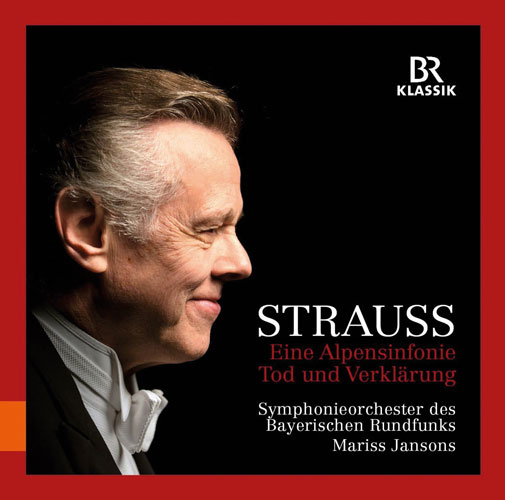

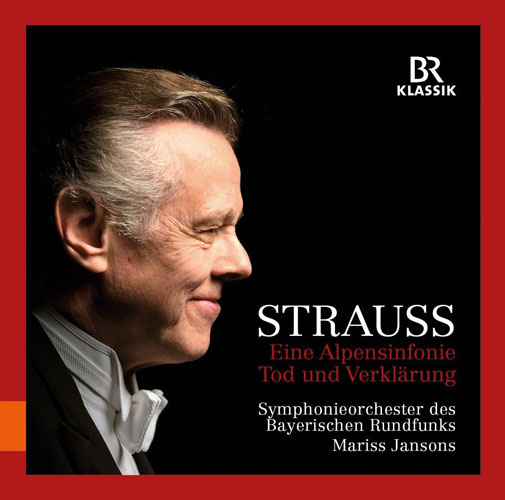

François-Xavier Roth, recorded in 2014 with another German radio orchestra, the SWR Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden and Freiburg (on SWR), offers supreme lucidity and clarity, but he’s trumped by the newest offering from Mariss Jansons, with the Bavarian RSO (far more vivid to my ears than his 2007 Concertgebouw recording on that orchestra’s own label – A/08). Indeed, this is probably the best-played account of all: a real sonic spectacle in which the strands of Strauss’s score are made to sparkle anew. Jansons misses the knottier philosophical dimension, but for Eine Alpensinfonie as orchestral showpiece this account is hard to beat – and it easily supplants Franz Welser-Möst’s somewhat earthbound 2010 BR-Klassik reading with the same orchestra (9/14).

Further afield

Away from the European heartlands, Kent Nagano’s 2014 account with the Gothenburg Symphony for Farao (A/16) is perfectly respectable but ultimately underwhelming. But there’s a real dark horse from the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra under Frank Shipway. I miss an extra touch of warmth in the final pages, but the veteran British conductor brings a firm, coherent vision to the score, and the orchestra, brilliantly recorded, play out of their skins for him – listen to the furious string tremolos as we get to the summit, the sheer excitement of their ‘Vision’, or the accuracy of the semiquavers going into the storm.

From the other side of the world, Jakub Hrůša’s generous, sweeping but rather broad account – very impressively played and recorded (in 2013) – with the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra (Exton) seems to have been available on disc only briefly before moving to download only. Daniel Harding is at the helm of a thrilling performance recorded live with the Saito Kinen Orchestra on Decca – a terrific showcase, if an account that fails quite to capture the mellower end of the score’s spectrum.

There are some very respectable offerings from UK orchestras, too. Gerard Schwarz’s 2001 account with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic on Avie (12/05) takes some beating in terms of sheer pictorial vividness (have the bird calls on the meadow ever sounded more alive?); and Andris Nelsons (2010) offers a characteristically lucid and attentive account with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on Orfeo (6/11). That performance never really digs far below the work’s surface, though, while Bernard Haitink’s 2008 recording for LSO Live is impressively symphonic in conception but occasionally rather uninvolving – the first third is somewhat leisurely and the final minutes are short on emotion, even if the work’s central episodes are masterfully controlled.

Ausklang

So, like Eine Alpensinfonie itself, we come full circle, to return to what the piece should and can be in performance. Numerous accounts in what’s largely a very high-quality discography, populated primarily with conductors who clearly really believe in the work, give us a very good idea. But it’s the first of the digital age – conducted by an Austrian who knew both Strauss and the Alps intimately – that remains for me the most persuasive, affecting realisation of the score’s multiple levels. Some subsequent accounts have shown a greater level of technical perfection, but none achieves the thrilling, moving mixture of the visceral and the reflective, or conveys the ever renewing power of nature and man’s (and art’s) relationship to it, quite as Karajan does with his Berliners.

Top Choice

Berlin Philharmonic / Karajan

DG

Karajan and his mighty Berlin forces introduced Eine Alpensinfonie to the CD era in a recording that makes compelling sense like no other: an exhilarating, moving and supremely satisfying performance defined by glorious lyricism and cohesiveness.

The roller coaster

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Kempe

Testament

Kempe’s Dresden account is justly famous, but this London recording with the RPO on thrilling, heroic form – terrifically remastered by Testament – is an exciting alternative to the better-behaved performances by central-European bands.

The Romantic choice

Vienna Philharmonic / Thielemann

Opus Arte

Helped by the rich, burnished playing of the Vienna Philharmonic, this account from the Salzburg Festival shows Thielemann’s generous, big-hearted and expansive approach to the score to best advantage.

The showcase

Bavarian RSO / Jansons

BR-Klassik

With its sheer technical splendour, this is an account of breathtaking clarity and virtuosity – taken from live performances – captured in stunning sound. Jansons doesn’t look too far beneath the surface – but what a surface!

Selected discography

Date / Artists / Record company

1941 Bavarian St Orch / Strauss / Preiser

1952 RIAS SO, Berlin / Böhm / Audite

1952 VPO / Knappertsbusch / Urania

1962 Leningrad PO / Mravinsky / Profil

1966 RPO / Kempe / Testament

1971 Staatskapelle Dresden / Kempe / Warner/EMI

1980 BPO / Karajan / DG

1985 Concertgebouw Orchestra / Haitink / Philips

1988 San Francisco SO / Blomstedt / Decca

1993 Staatskapelle Dresden / Sinopoli / DG

1998 Bavarian RSO / Maazel / RCA

2000 VPO / Thielemann / DG

2007 WDR SO, Cologne / Bychkov / Profil

2008 LSO / Haitink / LSO Live

2011 VPO / Thielemann / Opus Arte

2012 Saito Kinen Orch / Harding / Decca

2012 São Paulo SO / Shipway / BIS

2015 Frankfurt Op & Museum Orch / Weigle / Oehms

2016 Bavarian RSO / Jansons / BR-Klassik

This article originally appeared in the 2017 Awards issue of Gramophone. To read fascinating and authoritative features about the greatest classical works every month, subscribe to Gramophone: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe