Verdi's Falstaff: a complete guide

Gramophone

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Jeremy Nicholas reveals Verdi's creative process, Bryn Terfel discusses the challenges of Falstaff, plus a guide to key recordings

The creation of Falstaff, by Jeremy Nicholas

‘Excellent! Excellent,’ enthused Verdi to his friend Arrigo Boito on July 6, 1889. ‘Now [Falstaff or Merry Wives] can take shape and become reality! When? How? Who knows?’ The next day he wrote again to Boito having second thoughts, wondering if he would have the strength to finish the music and not wanting to waste Boito’s time, yet unable to suppress his delight at the prospect of teaming up again with his friend, finishing his letter by saying, ‘What a joy to be able to say to the public, “Here we are again!! Come and see us!”’

Boito reassured him: ‘You have longed for a good subject for a comic opera all your life, which proves you have a natural aptitude for the noble art of comedy. Instinct is a good guide. There is only one way to end your career more splendidly than Otello, and that is to end it with Falstaff.’ ‘Amen,’ replied the composer. ‘So be it! We’ll do this Falstaff, then. Let’s not think now of the obstacles, of age, or of illness! But I want to keep it the deepest secret: a word I underline three times to tell you that no one must know anything about it.’

What Boito had sent to Verdi was his synopsis for a libretto based on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor. Three years after the phenomenal success of Otello, Verdi would have had good reason to believe that his operatic career was over, finishing on a note of triumph. But Boito knew full well that the 75-year-old composer had long been fascinated with the character of Falstaff and that, moreover, he had always harboured an ambition to write a successful opera buffa ever since the failure of his one attempt at the genre, Un giorno di regno, in 1840.

Did The Merry Wives of Windsor, flimsiest of farces and one of the Bard’s weaker plays (written, it would seem, in a hurry) have sufficient dramatic conflict and character interest for the master musical dramatist? When we come out of the cinema or switch off the TV after watching a disappointing adaptation, we often hear someone say, ‘nothing like as good as the book’. Boito, with Verdi’s help, provided a rare exception: a libretto that was better than the play. He achieved this in a number of ways. First, by condensing Shakespeare’s plot and tightening the structure: for example, the Fat Woman of Brentford episode, the second of Falstaff’s ‘trials’, is excised; the Fenton–Anne love story is dispensed in brief snatches (Boito wrote to Verdi, ‘I should like, as one sprinkles sugar on a tart, to sprinkle the whole comedy with that gay love, without collecting it together at any one point’). Secondly, Boito introduces in a masterly way glimpses of the great Falstaff from Henry IV Parts 1 & 2 by lifting at least eight passages from the earlier plays, most notably the famous soliloquy about honour. Finally, Verdi, the astute and experienced man of the theatre, having realised that the linen basket scene in Act 2 was the dramatic high point of the piece and that Act 3 might prove to be an anticlimax, cleverly overcame this by ensuring that the music rose to ever more impressive heights: the enchanting fairies’ music, the love music, and culminating in the great fugal finale, ‘Tutto nel mondo è burla’ (‘Everything in the world’s a jest’) – a joyful rejoinder to the pessimism of Jacques’ ‘All the world’s a stage’ speech from As You Like It. The reason for Verdi’s insistence on secrecy was fear of failure: fear of writing another unsuccessful comic opera, fear of his final work being a flop. When news eventually did (inevitably) leak out, Verdi informed his publisher-friend Ricordi that he was writing it purely to pass the time. ‘So then, why make plans and undertake obligations, however indeterminately worded?’ No one was going to put him under pressure of any kind. ‘When I was young, despite ill-health I was able to stay at my desk for 10 or 12 hours, working constantly…I can’t do that now.’

Verdi began composing Falstaff in the last week of July 1889. Act 1 was completed on March 17 the next year. Little progress was made during the summer months, when Verdi was reluctant to work, but proceeded steadily during the autumn and winter. For the first three months of 1891 he wrote nothing, perhaps affected by the deaths of two younger, long-standing friends. Boito once more gently encouraged him with jokes and banter, and by June, Verdi was hard at work again, in September taking the unusual step (for him) of orchestrating all the music he had completed up till then (‘I’m afraid of forgetting certain blends and colours of instrumentation’). Act 1 had been scored by April 1892. The whole opera was completed in September – in other words, it was a little over three years from start to finish. Its premiere was booked into La Scala for February 9, 1893.

Emma Zilli was cast as Alice, Antonio Pini-Corsi as Ford, Giuseppina Pasqua as Mistress Quickly, Edoardo Garbin as Fenton (‘though he’s had no experience, and he knows nothing about music,’ wrote Verdi) and Garbin’s fiancée Adelina Stehle as Nannetta.

And for the eponymous title-role? There was only ever one name in the frame: Victor Maurel. But the creator of Iago made such extravagant demands for fees and exclusive rights that he very nearly scuppered the whole enterprise. ‘Never has such a thing happened to me in my 50 years in the galleys,’ wrote the composer, threatening to withdraw the opera should Maurel’s wishes be granted. In the event, Maurel backed down. Piano rehearsals began in November at Verdi’s home, Sant’ Agata, and on January 2, 1893 they moved to Milan, where Verdi supervised the orchestral rehearsals, some of them lasting up to eight hours a day.

The premiere on February 9 was a triumph generating scenes that are hard to imagine in 2013: a composer being mobbed outside his hotel and then called out on to the balcony of his room three times by the crowd below. By the end of the year there had been productions of Falstaff in Rome, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Trieste and Vienna. Paris first saw it (in French) in April 1894, London in May 1894, and New York in 1895, the last two incorporating Verdi’s extensive revisions to the score.

Bryn Terfel on Falstaff

By taking on Falstaff, I was stepping into the shoes of some rather famous Welshmen, not only on the opera stage but on the dramatic stage as well. Hugh Griffith was an incredible Falstaff on stage and many people commented on the similarities between us, so I was keen to read his autobiography. And then, of course, Sir Geraint Evans famously parked his entire being within the role of Falstaff, travelling the world with the Covent Garden production.

I managed to talk to Sir Geraint in the brief moments when he would actually stop and breathe for a little bit (that guy was hard to corner), and (famously) he told me to get a new suit. He also told me that my presence on the stage, be it in the operatic world or in concert, has to be something that holds the eye of whoever is spending their hard-earned cash to see me. And he warned me about the first scene of Falstaff and of the wardrobe hurdles that the role presents: the false bellies, the wigs, the moustaches and beards that constantly get in the way.

My transition into the role of Falstaff was interesting. With Welsh National Opera I sang Ford, which in essence is the eye-opener – you get to learn by watching whoever is performing Falstaff. In my case it was Donald Maxwell. It was a tremendous production, incredibly detailed, fabulously portrayed by every character. As the director Peter Stein said, Falstaff is like a Flemish painting with one main character in the middle, but every character has a life of their own. The cast had all performed the production before, and I was the newcomer as Ford, replacing David Malis. I made sure I was in every rehearsal to watch Stein work with Maxwell on Falstaff’s character, which was something of an epiphany for me – it really confirmed in my mind that I had made the right choice to follow my dream to become an opera singer.

The first time I took on the role of Falstaff was in Australia in 1999. I’d studied it, I’d been through it with Italian coaches, I’d read Evans’s, Griffith’s and Tito Gobbi’s autobiographies, but none of it helps you when you start to sing that first scene for the first time, ending with that incredible monologue (‘L’honore’). It’s a killer! I tried my best in that production but I never really nailed it. Then I came to Wales, I did it there, tried my best, and I still never nailed it. I did it at Covent Garden, I don’t think I got it there either. And I still haven’t nailed it. It’s a thorn in my side.

The monologue is the bane of my life! By the time I get there I’m breathless and my technique goes out of the window. I think the bass-baritone voice has the most trouble with that little section, whereas baritones probably love it. Maybe I come into my own in the monologue after coming out of the Thames – baritones perhaps would struggle with that. It’s a very interesting equation, the role of Falstaff.

I’m not a Premiership Falstaff yet, I’m in the First Division, I think. I still have something to say about this role. With Falstaff I always have this tremendous urge to go totally over the top and just convey everything that Verdi wrote. I think the next time I do it, less will be more. And maybe it’s a cheeky strategy on my part to say that I’ve never nailed it, it’s really just a reason to do it again.

The role of Falstaff came out of the mould of the classic Verdi baritone roles; Verdi gave us mortals (bass-baritones) a chance to sing his notes. It doesn’t go above the stave very often, the lines aren’t too daunting. I think the role is beautifully paced. Think of the second act of Don Giovanni; I never, ever felt comfortable with that role (should never have sung it really), but I couldn’t have gone through my career not being Don Giovanni. His succession of duet, recit, trio, recit, aria, recit, duet, etc, never fell in my lap as something I was very comfortable with. But in Falstaff, once you’ve got through the monologue and feel happy that it went OK, the rest of the evening is like Horowitz playing Schumann’s Traumerei on a stage in Moscow – you know, throwing his handkerchief on the piano and just smiling, playing and walking off. It’s that kind of role; it gives great satisfaction.

I’m doing Falstaff twice at La Scala in 2013, which I’m thrilled about because I want to be in the Guinness Book of Records some day for being the singer that gave the most performances of Falstaff around the world.

Falstaff – a recording history, by Jeremy Nicholas

Of the myriad recordings of Falstaff that have been issued, none I’ve heard has the completely ideal cast, orchestra, conductor and sound all combined, but several come pretty close.

Remarkably, there’s a 1907 recording of Maurel singing a snatch of the role he created: ‘Quand’ero paggio’. In fact, he sings it three times in succession, the end of each ‘verse’ greeted bizarrely with applause and cheers (Marston 52011-2 – nla).

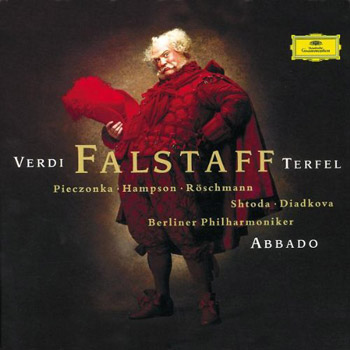

Without any set-piece arias, very little else of Falstaff was captured on disc until the full opera had its first commercial recording in 1932, with Lorenzo Molajoli leading some of La Scala’s finest (Giacomo Rimini as Falstaff, Pia Tassinari as Alice) in a vivacious account that sounds amazingly good for its age (Naxos 8 110198/99). But it can’t compare with the live performance conducted by Arturo Toscanini in 1950. This has always been held up as the benchmark, and with good reason. Quite apart from the obvious attraction of it being led by someone who knew the composer personally and had been conducting the work for 56 years, one is struck not just by the crisp detail of the orchestral playing and Toscanini’s youthful high spirits (he was 83 at the time) but also by the sense of a cast singing what’s essentially a chamber work. The ladies in particular are terrific, but the robust Falstaff of Giuseppe Valdengo misses out on the fun element (RCA 74321 72372-2). ‘For my taste,’ said Carlo Maria Giulini, ‘[Falstaff] cannot be too serious.’ This shows in his 1982 recording (DG 477 6498). Claudio Abbado’s highly praised 2001 recording is detailed but laboured, with Bryn Terfel doing a lot of acting as Falstaff (DG 471 1942). Compare him with the faux dignity of the great Mariano Stabile, who sang the role more than 1200 times and can be heard in a live performance from 1952 conducted by Victor de Sabata (Music and Arts MACD1104). Georg Solti’s hard-driven 1963 account will appeal to some, and it features Geraint Evans as a Falstaff to match Stabile (Decca 475 6677).

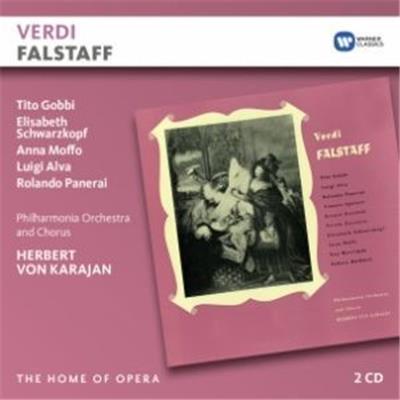

Herbert von Karajan’s 1980 version is heavy-handed, with Giuseppe Taddei in the title-role past his vocal prime (Decca 478 4167). What a contrast to Karajan’s 1956 recording with the wily and ebullient Tito Gobbi as the fat knight, Fedora Barbieri as a fruity Mistress Quickly, Anna Moffo as perhaps the best of all Nannettas, and Rolando Panerai as a superb Ford (Panerai, incidentally, is an excellent Falstaff in the earlier – 1991 – and preferable of Colin Davis’s two recordings: RCA 88697 45801-2). Add to that the Philharmonia at its height (Dennis Brain plays the horn solo at the start of Act 4 scene 2) and an approach clearly influenced by Toscanini (whom Karajan heard conduct the opera several times as a young man) and you have a Falstaff to laugh with and live with.

Essential recording

Falstaff

Gobbi; Alva; Panerai; Schwarzkopf; Moffo; Barbieri; Philharmonia Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

(Warner Classics)

Explore Verdi's operas...

Macbeth: a complete guide

Richard Wigmore reveals Verdi's creative process, Gianandrea Noseda provides unique insights, plus we give a guide to the greatest recordings... Read more

La traviata: a complete guide

Mike Ashman looks into the opera's genesis, Renée Fleming reflects on the role of Violetta, plus a guide to the key recordings... Read more

Aida: a complete guide

Richard Wigmore explores Verdi's creative process, Sir Mark Elder reflects on Verdi's masterpiece, plus we give a guide to the greatest recordings... Read more