Verdi's Otello: a guide to the best recordings

Richard Lawrence

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

The past eight decades have seen many recordings of this tenor-led operatic masterpiece. Trawling through them all, Richard Lawrence finds at least three very special Otellos, and some electric conducting

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

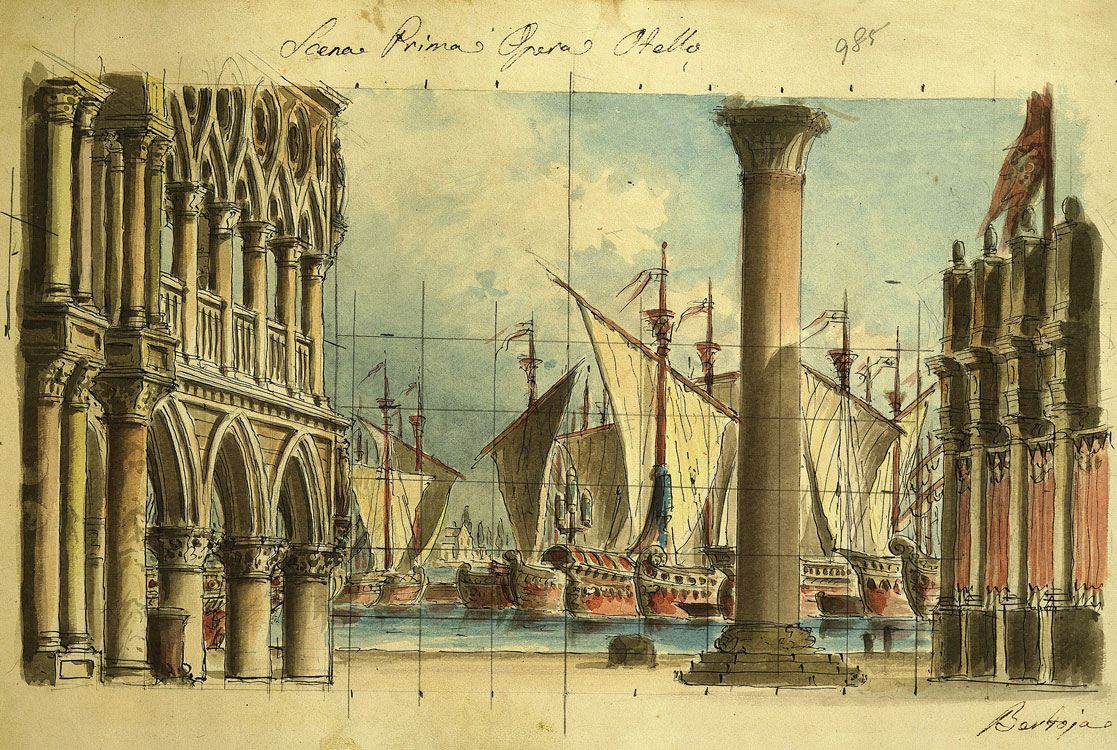

Verdi and Wagner were almost exact contemporaries, born a few months apart in 1813. Wagner died at the age of 69 in 1883; Verdi was 87 when he died in 1901. How would posterity rate Verdi if he, too, had died in 1883? It’s possible that without the final operatic masterpieces, Otello and Falstaff, his reputation would rest primarily on the Requiem of 1874. We have God to thank for Verdi living on. For Verdi living on to compose Otello we have to thank Giulio Ricordi, his publisher, who planted the idea in 1879, and Arrigo Boito, the librettist: between them they played the initially dubious Verdi with infinite tact and encouragement. Boito, a composer himself, produced a superb, taut libretto that improved on the original by, among other things, dropping Shakespeare’s Act 1 and setting the entire action in Cyprus. The premiere at La Scala, Milan, on February 5, 1887, was a huge success. The cast was led by Francesco Tamagno, who had previously sung Gabriele Adorno in the revised Simon Boccanegra and the title-role in the four-act Don Carlo. The part of Otello has been one of the pinnacles of the tenor repertoire ever since; but it’s worth noting that until a very late stage the opera was to be called Iago.

The early recordings

Our first recording comes from La Scala in 1931/32, and it’s astonishingly good for its age. Carlo Sabajno gets disciplined singing from the chorus in Act 1 (‘Vittoria!’ and ‘Fuoco di gioia!’). Nicola Fusati and Apollo Granforte as Otello and Iago are imprecise with their rhythm, but Fusati has ringing top notes and Granforte colours his tone to excellent effect. Like many of his successors, Fusati misaccentuates the opening phrase of Otello’s monologue in Act 3: this may have soon become common practice, but it’s correct on the Toscanini recording – and Toscanini played in the orchestra at the premiere. There’s a weedy cor anglais in Act 4, but overall this is well worth hearing. Almost as good, but in variable sound, is the broadcast from the New York Met in 1938. There’s plenty of fire to Ettore Panizza’s conducting – Otello’s smothering of Desdemona is as vivid as Fafner clubbing Fasolt to death in Das Rheingold – but the USP is the chance to hear Giovanni Martinelli, the reigning Otello of the day. He starts the first phrase of the love duet a bit flat – as does Fusati, come to that – but soon improves. Lawrence Tibbett is a subtle, understated Iago.

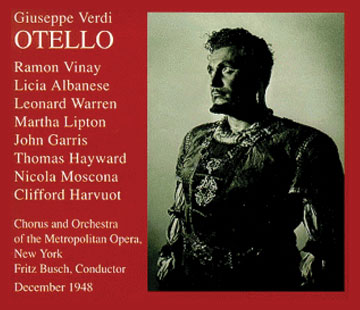

Ramón Vinay

The leading Otello in the years immediately after the Second World War was the Chilean tenor Ramón Vinay. He began his professional career as a baritone, and it’s the baritonal darkness of his voice that informs his recorded performances. There’s a live 1955 recording from Covent Garden under Kubelík (9/06; available on iTunes and elsewhere as a download), but here we will focus on three earlier ones, of which two are outstanding. The famous one is Arturo Toscanini’s, assembled from NBC broadcasts in 1947. The conducting is electric, it goes without saying. Toscanini coached Vinay in the part, and the singer repaid his mentor with a performance of searing intensity. Giuseppe Valdengo’s Iago is not quite of this calibre; neither is Herva Nelli, who runs out of puff at the end of Desdemona’s first sentence. Two unusual features are the use of solo voices in the scene with the children; and (even harder to justify) the cellos doubling the double basses at the octave when Otello enters to murder his wife.

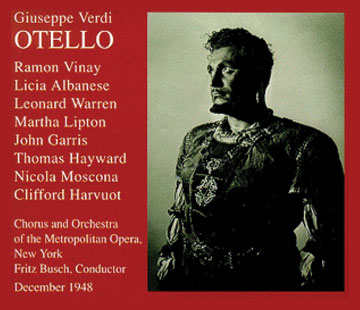

Less familiar is the version from the Met, broadcast a year later. Fritz Busch’s conducting is immensely exciting. The Act 1 choruses are vivid; the brass is menacing as Otello waits to eavesdrop on Iago and Cassio; and the full orchestra, tutta forza, at the smothering of Desdemona is stupendous. Vinay is even more moving than he was for Toscanini. As for Iago, the sudden pianissimo as he warns Otello of jealousy, and the curl of the lip as he recounts Cassio’s supposed dream, are but two instances of the way Leonard Warren acts with his voice. Licia Albanese, whether loving, wheedling or despairing, is an excellent Desdemona.

The Vinay performance under Wilhelm Furtwängler, live from Salzburg in 1951, is not so well recorded, the sound tinny when it isn’t harsh. The all-important opening ‘Esultate!’ that establishes Otello’s authority comes from upstage and is taken too fast, thereby lessening the impact. But Furtwängler, like Busch, doesn’t accelerate at the end of the vengeance duet, thereby very definitely increasing the impact.

The age of stereo

Further live performances by Vinay from the 1950s have appeared over the past few years, but it was some time before Otello benefited from a recording in stereo. Mario Del Monaco, only three years younger, was soon treading on Vinay’s heels. His 1950 recording on Myto from Buenos Aires, billed as his first ever Otello, can safely be ignored. A studio recording in mono that appeared on Decca in 1954 with Alberto Erede conducting is no longer officially available. In 1961, however, the same principals featured in a stereo version in which the opera was given the full Decca treatment, with the stage movement and balance that are associated with John Culshaw (the producer here, with Christopher Raeburn). It is not a subtle performance. Del Monaco is rhythmically imprecise at his first entry, lumpy in the love duet, ungainly in his phrasing of ‘eburnea mano’ and, later in Act 3, hammy at ‘Dio! mi potevi scagliar’. Aldo Protti delivers Iago’s Credo powerfully, but he makes little of the insidiousness of ‘Cassio’s dream’. Renata Tebaldi, on the other hand, phrases beautifully and is effectively restrained at her farewell to Emilia. Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic are terrific; but the main reason for buying this set is to experience the Act 3 ballet that Verdi was obliged to add for the Paris Opéra in 1894 – if only to confirm your views about 19th-century Parisian taste.

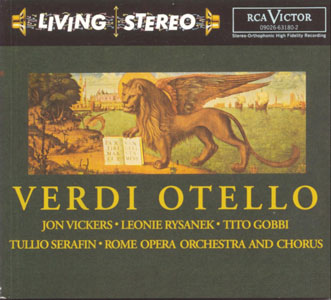

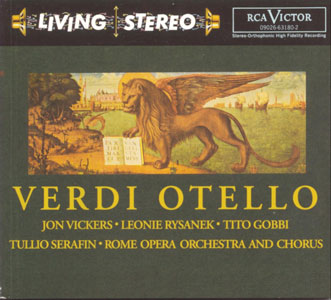

Better by far is the performance conducted by Tullio Serafin from the year before (1960). The Rome Opera Orchestra is not in the same league as the Vienna Philharmonic, and the recording quality is not state-of-the-art; the principals, though, are magnificent. Jon Vickers had not then sung the role on stage, but his interpretation has a maturity to be wondered at. ‘Dio! mi potevi scagliar’ is near perfect: correctly accentuated, sung mezza voce with no muttering, truly dolcissimo at ‘l’anima acqueto’. If the top B flats aren’t quite there in the duet with Iago, the love duet has a manly robustness and the final ‘Un bacio’ as he lies dying is tenderness itself. His Desdemona, Leonie Rysanek, is a match for Tebaldi in her passionate dignity; Tito Gobbi, the leading Iago of the time, rightly eschews maniacal laughter after the Credo, then chills the blood at ‘È un’idra fosca’. Serafin misses nothing: note, for instance, the chromatic phrases for cornet and trumpet when Otello speaks of battle in the love duet. By the time Vickers came to record the role for Herbert von Karajan in 1973 he had sung it many times in the theatre. He is just as authoritative, just as tender as he had been for Serafin; unfortunately, the recording is marred by too wide a dynamic range, and there’s a cut in the Act 2 chorus as well as the more common abridgement of the concertato in Act 3.

After Serafin there was a long gap before the appearance of a new studio version from EMI. The critics expressed disappointment in John Barbirolli, especially in comparison with an idiomatic Madama Butterfly recorded in Rome a year or two previously. The star was James McCracken, who had had enormous success at Covent Garden. Without his imposing physical presence, however, McCracken comes across as rather two-dimensional, outclassed by Gwyneth Jones’s warm, womanly Desdemona. ‘Dio! mi potevi scagliar’ sounds hollow, as though recorded in a different acoustic. On the stage, McCracken’s nemesis was Gobbi; in the recording, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, as you would expect, brings a Lieder singer’s refinement to Iago’s music without matching Gobbi’s superb characterisation. Barbirolli keeps a firm grip on the vengeance duet but speeds up in the postlude.

The Otello of our time – on CD

The McCracken performances at Covent Garden were conducted by Georg Solti. In 1977, Solti made a fine – yet easily overlooked – recording in which Carlo Cossutta makes a strong entrance; and after the storm, the Vienna State Opera chorus manages a beautiful pianissimo. If Gabriel Bacquier’s Iago sounds strained here and there, Margaret Price sings exquisitely as Desdemona and Kurt Moll is a sonorous Lodovico. Cossutta curses his wife powerfully, but the high point is a well-sung ‘Dio! mi potevi scagliar’ with a really well-turned ascent to ‘quel raggio’. Solti’s 1991 recording was taken from concert performances in Chicago and New York. Luciano Pavarotti is open-throated but, to tell the truth, rather dull, as is Leo Nucci. Kiri Te Kanawa raises the tone, and Anthony Rolfe Johnson is a sensitive, almost delicate Cassio: not really enough of an incentive to buy.

The supreme Otello of our own time is Plácido Domingo. Like Vinay, he started out as a baritone, and has now of course reverted to singing baritone roles; perhaps he too – though I rather hope not – will take on the part of Iago. Domingo’s first studio version, conducted by James Levine, came out in 1978 – ‘Domingo’s Otello is a magnificent achievement,’ wrote Alan Blyth in his review for Gramophone. Domingo went on to enjoy a significant partnership with Carlos Kleiber at Covent Garden in the 1980s; it’s a great pity that no recording documenting this has been issued commercially, but there’s an ‘unofficial’ recording from La Scala (available on iTunes and elsewhere as a download), worth hearing for the slithery portamento that Kleiber gets from the strings as Piero Cappuccilli finishes his account of ‘Cassio’s dream’. For the 1985 EMI version, the La Scala orchestra was conducted by Lorin Maazel. This provided the soundtrack for the Zeffirelli film, of which more anon. As with Karajan in 1973, it’s often either too loud or too soft; but this stricture doesn’t apply to Justino Díaz, who is tellingly quiet at points in Act 2 and who is almost unique in singing a decent trill when Iago complains to Roderigo of being merely ‘his Moorship’s ancient’. Domingo gets off to a good start with a strong, accurate ‘Esultate!’, and sings with burnished tone throughout.

Even better is the live performance from Vienna in 1987. Anna Tomowa-Sintow lingers too much here and there but she is splendidly passionate: upfront, not wilting, she is memorable in the usually interminable Willow Song. Renato Bruson delivers a powerful Credo and is equally forceful when ordering Emilia to say nothing about the handkerchief. Domingo is again in fine voice, and Zubin Mehta presides over excellent work from chorus and orchestra. The sound, too, is excellent.

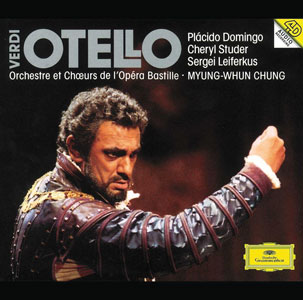

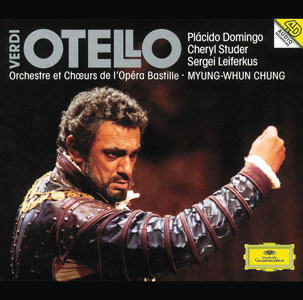

There’s no such drawback to the studio recording from Paris, made in 1993. Sergei Leiferkus, so bluff in the drinking song (with a precise, in-tune, downward chromatic scale), is vicious when he doffs the mask for his Credo. Cheryl Studer sings the Willow Song with pure tone, following it with an Ave Maria of great delicacy. Myung-Whun Chung favours fast speeds, but there’s still plenty of weight to ‘Sì, pel ciel’ at the end of Act 2. Above all, there’s Domingo again: urgent and ecstatic in the love duet, urgent and desperate with Iago – his thrilling crescendo at ‘Othello’s occupation’s gone’ matched by the conductor – and noble at the end.

There are some good things about Gustav Kuhn’s live 1991 recording from Tokyo (Koch Schwann, 6/92), especially Bruson’s Iago and Maria Guleghina’s Desdemona, but Corneliu Murgu’s stentorian, graceless Otello rules it out. That leaves, after another long gap on CD, Colin Davis’s live account from the Barbican Hall in London. At his entrance, Simon O’Neill breathes in the middle of the word ‘l’armi’; his tone, while not unpleasing, is rather thin. There’s some dodgy intonation in the Act 2 quartet, and a half-bar has gone missing near the very end. But this is worth considering as a bargain choice – and it includes libretto and translation.

Otello in translation

There’s a surprising number of recordings in the vernacular. Two come from Preiser. Singing in German, Torsten Ralf is trumpet-toned for Karl Böhm (Vienna, 1944), and Set Svanholm leads a fine Swedish-language performance for Sixten Ehrling (Stockholm, 1953/54). Two German recordings from Walhall also sound well. Under Herbert Kegel (Leipzig, 1954), Alexander Miltschinoff and Hans Löbel are both stately and gripping at ‘Sì, pel ciel’, as indeed are Hans Hopf and Josef Metternich for Solti (Cologne, 1958).

The particular appeal of the 1983 performance from ENO lies in Mark Elder’s adoption of Verdi’s revision for Paris of the Act 3 concertato. The standard version tends to hang fire – hence the cuts made by many conductors – and Iago’s plotting is usually inaudible in the theatre. Verdi tightened up the ensemble and thinned it out: an improvement, but one that hasn’t caught on. Charles Craig and Neil Howlett are first-rate – the latter’s trill is as good as Díaz’s, and his ‘Cassio’s dream’ is vivid – and, one or two problems of balance apart, the performance has a thrilling immediacy.

Otello on DVD

The first thing to say about the Zeffirelli film (EMI) is that it is Zeffirelli’s Otello, not Verdi’s. In a word, the score has been butchered. And the second thing is that the recording has been transferred more than a semitone too low. (It’s conducted by Maazel, and the CD version mentioned above is complete and at the correct pitch.) It is cheesily enjoyable, but there should be a printed warning. The Karajan (1972/73) is also a lip-synched film, directed by the conductor himself. This is full of telling detail: Otello’s dangerous smile in his fraught scene with Desdemona, his shadow on the wall as he enters in Act 4, the ring falling off his finger as he strangles her. As on the CD recording (seemingly not the soundtrack for the film), Vickers is excellent both as warrior and as lover; the many reaction shots point up Peter Glossop’s skill as an actor, and Mirella Freni is touching as Desdemona.

Iago does his laugh after the Credo, the audience applauds – and the music stops. We can only be at the Arena in Verona. The 1982 production by Gianfranco de Bosio, conducted by Zoltán Peskó, is actually not bad. Vladimir Atlantov was always more loud than anything else and he fully meets one’s expectations here, but he manages a restrained, moving ‘Niun mi tema’. Apart from the ‘unofficial’ Kleiber CD, this is the only example of the Iago of Cappuccilli, a really fine Verdi baritone. Te Kanawa rises magnificently to Desdemona’s outburst at ‘E son io l’innocente cagion’.

The other open-air production is from the Doge’s Palace in Venice. This is imaginatively staged by Francesco Micheli, with a clever use of video projections by Sergio Metalli. Surrounding Iago with devils during his Credo gives him an inappropriately Mephistophelian character, though; and some might jib at the ending, where the dead Desdemona and Otello both rise before walking off hand in hand. Myung-Whun Chung is well in command, and Gregory Kunde’s well-acted Otello is more tenorish than many of his colleagues in the part.

The remaining three recordings all feature Domingo. The last one, from La Scala in 2001, marked his farewell to the role. In his sixties by then, he unsurprisingly has trouble with the top notes. Nucci, also a veteran, transposes the second part of ‘Cassio’s dream’ down an octave. Graham Vick cleverly has Barbara Frittoli’s Desdemona playing blind man’s buff with the fateful handkerchief in the children’s scene. Like Elder, Riccardo Muti opts for the Paris version of the Act 3 concertato.

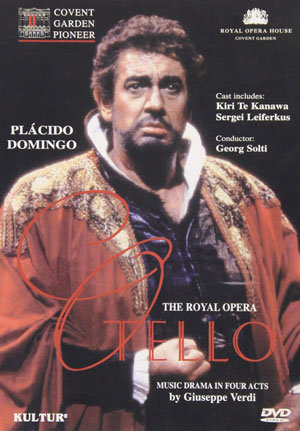

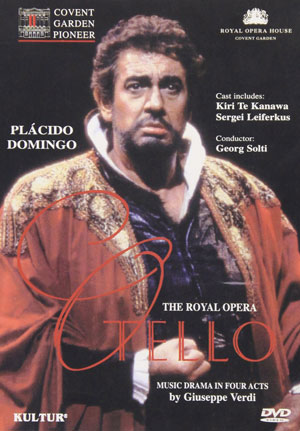

If this were the only visual record of Domingo’s Otello it would be treasurable; but we are fortunate to have two more that are even better. Both are directed by Elijah Moshinsky, with Brian Large as the video director. They’re different productions, both with costumes – again, different – by Peter J Hall. Not surprisingly, though, there are points of similarity. Iago is very much the secretary, with papers for Otello to sign; during ‘Era la notte’, the camera shows Otello’s misery. And both sets for Act 3 have an enormous painting at the back – hard to make out, but possibly a Deposition from the Cross in the manner of Titian or Tintoretto. Georg Solti and James Levine give superlative accounts of the score, and Domingo is utterly magnificent. When it comes to performances of this quality, comparisons become meaningless. For Solti, Leiferkus is hail-fellow-well-met, with that characteristic, highly individual edge to his voice; for Levine, James Morris, smoother of tone, has a nice line in ironic smiling. Neither Te Kanawa nor Renée Fleming can be faulted, the latter especially memorable in her perfectly floated ‘Salce!’ in the Willow Song. How lucky we are that Verdi lived on – and there was still Falstaff to come!

The Top Choice

Opéra Bastille / Chung

Domingo and Leiferkus again on top form, with a tender, vulnerable Desdemona from Cheryl Studer and impeccably responsive conducting from Myun-Whung Chung. Almost as good are Domingo and Bruson in the live performance from Vienna under Zubin Mehta.

Stereo Choice

Rome Opera / Serafin

What a pity that Tito Gobbi’s Iago was never captured on film. But this recording is treasurable all the same, with Gobbi partnered by the young Jon Vickers. Leonie Rysanek is in fine voice as Desdemona, and Tullio Serafin conducts superbly.

Historic Choice

New York Met Opera / Busch

The historic choice has to be one of the performances starring Ramón Vinay, the outstanding Otello after Martinelli and before Domingo. By a small margin, this one from the New York Met under Fritz Busch is the one to go for. Otherwise, the famous Toscanini set is still magnificent.

DVD Choice

Royal Opera / Solti

This misses being top choice only because it’s so hard to choose between Solti and Levine in productions by Elijah Moshinsky. Domingo is unbearably moving in both; perhaps Sergei Leiferkus just has the edge over James Morris, but it’s a near thing.

Selected Discography

Date / Artists / Record company

1931/32 Fusati, Carbone, Granforte; La Scala, Milan / Sabajno / Preiser

1938 Martinelli, Rethberg, Tibbett; NY Met Op / Panizza / Naxos

1947 Vinay, Nelli, Valdengo; NBC SO / Toscanini / RCA; Naxos; Opus Kura

1948 Vinay, Albanese, Warren; NY Met Op / Busch / Preiser

1951 Vinay, Martinis, Schöffler; VPO / Furtwängler / Archipel

1960 Vickers, Rysanek, Gobbi; Rome Op / Serafin / RCA

1961 Del Monaco, Tebaldi, Protti; VPO / Karajan / Decca

1968 McCracken, Jones, Fischer-Dieskau; New Philh / Barbirolli / EMI (Warner)

1972/73 Vickers, Freni, Glossop; BPO / Karajan / DG

1973 Vickers, Freni, Glossop; BPO / Karajan / EMI (Warner)

1977 Cossutta, Price, Bacquier; VPO / Solti / Decca

1978 Domingo, Scotto, Milnes; Nat PO / Levine / RCA

1982 Atlantov, Te Kanawa, Cappuccilli; Verona Arena / Peskó / NVC Arts/Warner Vision

1983 Craig, Plowright, Howlett; ENO / Elder (sung in English) / Chandos

1985 Domingo, Ricciarelli, Díaz; La Scala, Milan / Maazel / EMI (Warner)

1987 Domingo, Tomowa-Sintow, Bruson; Vienna St Op / Mehta / Orfeo

1991 Pavarotti, Te Kanawa, Nucci; Chicago SO / Solti / Decca

1992 Domingo, Te Kanawa, Leiferkus; Royal Op / Solti / Opus Arte

1993 Domingo, Studer, Leiferkus; Op Bastille, Paris / Chung / DG

1995 Domingo, Fleming, Morris; NY Met Op / Levine / DG

2001 Domingo, Frittoli, Nucci; La Scala, Milan / Muti / TDK; ArtHaus

2009 O’Neill, Schwanewilms, Finley; LSO / C Davis / LSO Live

2013 Kunde, Remigio, Gallo; La Fenice, Venice / Chung / C Major

This article originally appeared in the April 2016 issue of Gramophone. To explore our latest subscription offers, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe