Beethoven Piano Concertos

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 3/1989

Media Format: Vinyl

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 421 718-1DH3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, 'Emperor' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Cleveland Orchestra Chorus Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 3/1989

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 199

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 421 718-2DH3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, 'Emperor' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Cleveland Orchestra Chorus Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 3/1989

Media Format: Cassette

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 421 718-4DH3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, 'Emperor' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

| Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Cleveland Orchestra Cleveland Orchestra Chorus Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano |

Author: Richard Osborne

It has been done before, of course; a good deal with the early concertos, rather less often with the Fourth and Fifth Concertos. On record, Daniel Barenboim recently played and directed all five with the Berlin Philharmonic for EMI. I thought the performances sensible, often eloquent, and always interestingly discursive, though perhaps at times too much a solo discourse in front of an agreeable orchestral backdrop. Perhaps because Barenboim's youthful earlier EMI set with Klemperer and the New Philharmonia Orchestra had made so much of the creative cut-and-thrust of the musical debate in these concertos, I found the conductorless cycle comparatively bland, and not just in the later concertos. Without Klemperer, every inch the wild and wicked old man, to goad and cajole him, Barenboim was often a good deal less waggish in some of the spirited earlier works.

Ashkenazy has never recorded the concertos with a man of Klemperer's idiosycratic genius; but the Solti cycle was orchestrally first rate and continues to sound so on Decca's mid-price CD reissues of the Second and Fifth Concertos ((CD) 417 703-2DM) and the Third and Fourth Concertos ((CD) 417 740-2DM, 5/88). The later Mehta cycle with the VPO, currently available on four rather poorly filled full-price Decca LPs and CDs was less of a success, largely because of the conducting which was all too arbitrary: unassuming one moment, highly inflected the next, and likely to be plain slovenly a few bars further on.

The fact is, Ashkenazy is probably as good a Beethoven conductor now as Solti was in 1973 or Mehta in 1984. It is interesting to compare, for example, Ashkenazy's direction of the Third Concerto's somewhat infamous ritornello with Mehta's, or even Solti's. As Trevor Harvey noted in 1973, Solti is up to tempo more or less at once; crotchet=132 accelerating only slightly at bar 24 to crotchet=136. Mehta, by contrast, tries the old trick of starting at a sluggish 120 and then surging forward at bar 24 to a racey 138 (almost Czerny's recommended tempo!). Goodness knows what Ashkenazy made of that as he sat pondering his first entry. Of the three conductors, he is the only one to hold the same tempo throughout at what is for him an obviously comfortable but by no means comatose or undramatic crotchet=128.

But other things, too, come together to give the new set a quite special quality. Ashkenazy began with the advantage of an excellent working relationship with the players of the Cleveland Orchestra. With his long experience of directing Mozart piano concertos from the keyboard, he has been able to weld what sounds like a hard-picked extended chamber orchestra into an accompanying ensemble worthy to set beside the ECO at their best or even the Cleveland Orchestra who once upon a time, under Szell's direction, provided some wonderfully astute accompaniments for the second of Emil Gilels's EMI cycles. The distinction of the playing—the eloquence of the solo wind and string contributions, the robust yet thoroughbred tone, the accuracy and pliancy of the rhythms—is a joy. And Decca's engineers have surpassed even their own earlier efforts by providing sound of warmth and intimacy, with plenty of 'bottom' (always difficult with Beethoven's often idiosyncratic scoring) and with plenty of space into which the Fifth Concerto can issue its commanding summonses. By the set's own high standards, I sometimes thought the piano, the instrument itself, a shade off-colour in the Third Concerto (where the opening of the slow movement might have been re-taken to advantage) but the actual sound of the piano is, as so often with Ashkenazy, a thing of power and beauty most of the time.

In the past I have, I confess, not always thought Ashkenazy the most rigorous of Beethovenians; in the sonatas especially, recorded, it's true, over many years, salient detail can often pass by in what are always very beautiful sounding performances. But he has always been an effective interpreter of the concertos and now he seems, partly perhaps under the influence of his new dual responsibility, to be playing with a new rigour and insight. It is as though after two or more decades he is coming to know the works, completely, for the first time. The mix—experience and the thrill of seemingly new discovery—is always likely to generate memorable music-making.

Trevor Harvey found himself jotting down the word 'magical' time and again in 1973 and the raptness and beauty of the playing is still a source of wonder, only perhaps even more so. All the slow movements are fine but there seems to be a special quality in the strings' listening in the long diminuendo of the Fourth Concerto's slow movement. The slow movement of the Fifth is exceptionally lovely and the transitions to both finales is a totally absorbing affair. The start of the Fourth Concerto is also consummately done by soloist and strings alike.

Ensemble playing is throughout of a high quality, particularly in the difficult first movement codas, and rarely does Ashkenazy show any sign of being burdened by his dual responsibility. At first, I thought the piano's re-entry in the first movement of the Fifth Concerto a shade tentative. But the tempo is now broader, more magisterial and Ashkenazy, rather than announcing as some pianists seem to do, ''I'm back folks, listen to this!'', is in an evidently enquiring mood as the burden of the discourse is handed back to the keyboard. Once or twice he seems a shade dogmatic, all-powerful and producing an all-round regularity of accent; in the finale of the Second Concerto the piano really does need a foil. Solti was more gamesome here, a better devil's advocate for the sobriety the orchestra initially proposes. Sometimes Ashkenazy drives the sforzandos rather hard, but for much of the time—the whole of the First Concerto, the finale of the Fifth—the playing is physically exhilarating and mentally inspiring. The start of the Choral Fantasy, a splendid addition to the three-CD set, is riveting, and the orchestral playing is full of wit and earthy humour. Is the choir perhaps a shade cabined and confined acoustically? That, and the inevitable too loud entry of the piano in the cadenza of the first movement of the Third Concerto, are my only sound queries.

Cadenzas. Ashkenazy continues to use the long first Beethoven cadenza in the Fourth Concerto, here played with great eloquence and improvisatory charm, a great pianist in the heyday of his art. But, with typical consideration, Ashkenazy has now shifted to the shorter, wittier second Beethoven cadenza in the First Concerto, better scaled to his new manner; and in the Second Concerto he has revived his own cadenza, used with Solti. It is a nicely crafted piece that, like Lipatti's Mozart cadenzas, shows real musicianship whilst only occasionally straying forward a few years in harmonic manner.

Recently I suggested that Murray Perahia's CBS cycle with Haitink was the best general buy; and since it has stood the test of time and the critical scrutiny of such experienced judges as SP and RL, I think the recommendation stands. But the definitive cycle is as elusive as the philosopher's stone and in his latest cycle Ashkenazy and his Cleveland musicians give us some wonderful, absorbingly articulate music-making, expertly and lovingly recorded. To own this set is to be a privileged person; as I'm sure the late Edwin Fischer might have been the first to agree.'

Explore the world’s largest classical music catalogue on Apple Music Classical.

Included with an Apple Music subscription. Download now.

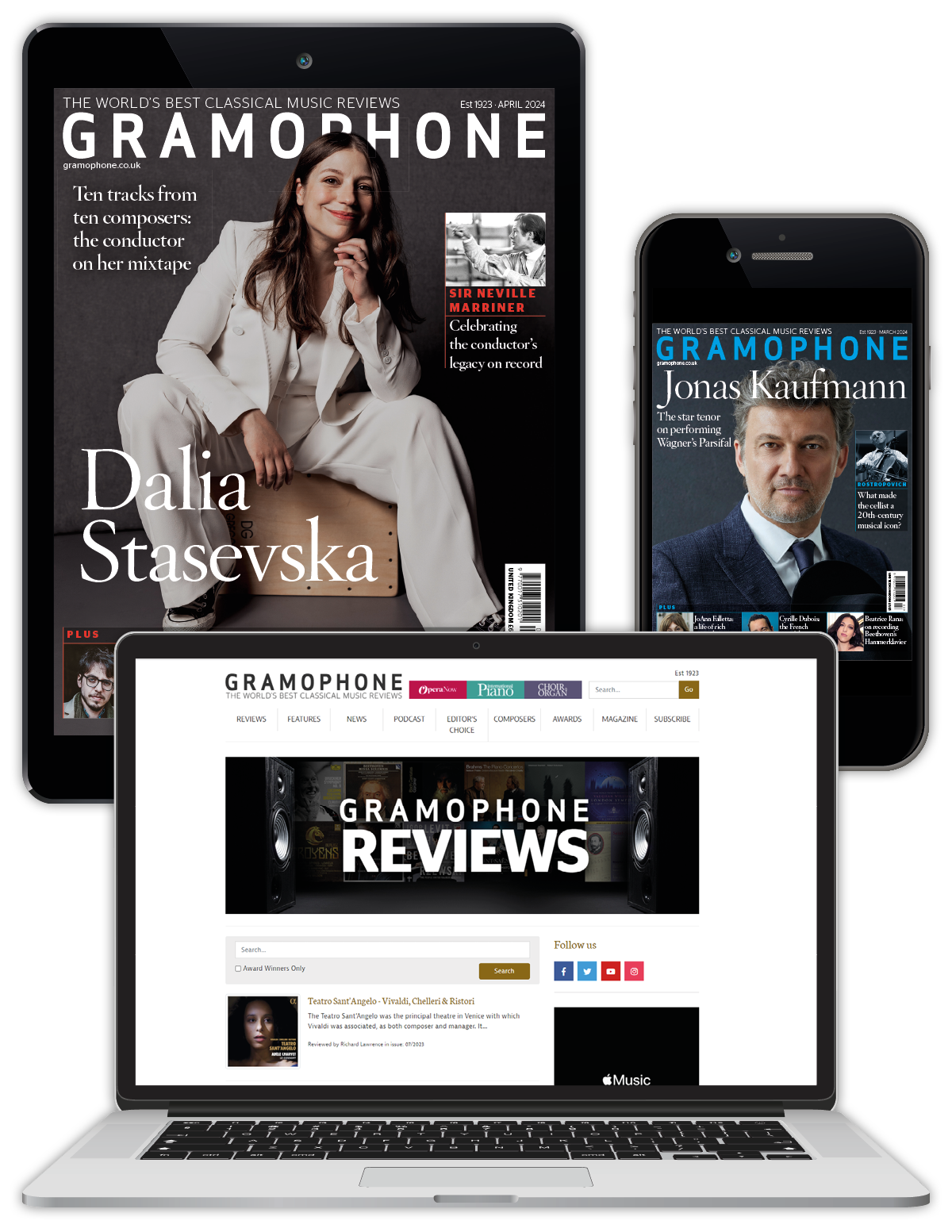

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.