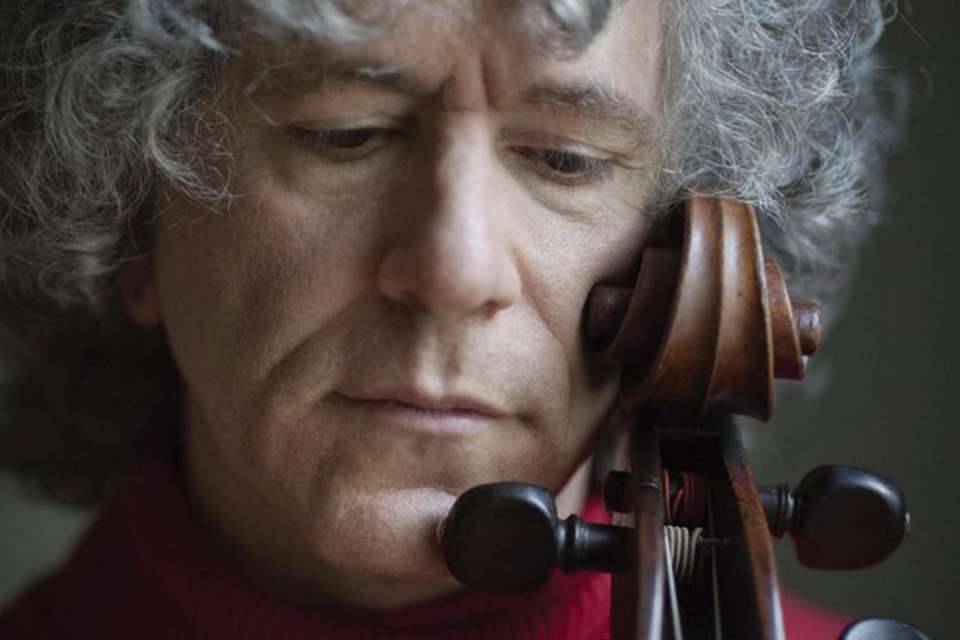

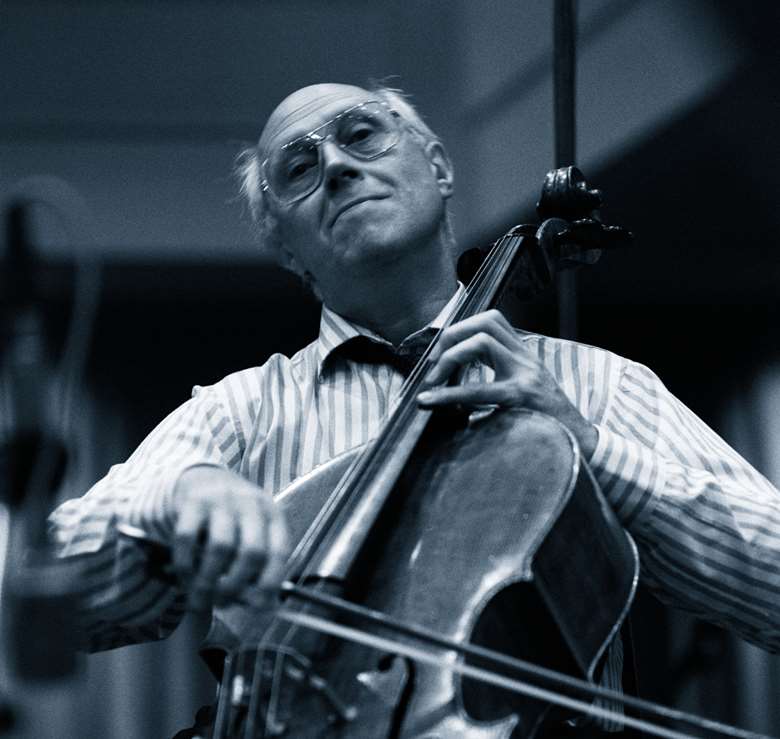

Rostropovich: what made the cellist a 20th-century musical icon?

Julian Lloyd Webber

Thursday, April 25, 2024

Julian Lloyd Webber celebrates the artistry of a legendary fellow cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich, a Russian musician who was an outspoken advocate of human rights and an inspiration for many composers

Countless musicians give me enormous pleasure and many others continue to inspire me, but only one has changed the course of my life – Mstislav Rostropovich. When I was around 11, my cello teacher Rhuna Martin nurtured my nascent love of the instrument by taking me to hear great cellists in concert. By the age of 13, I had witnessed quite a few of these remarkable performers, yet nothing had prepared me for the impact of Rostropovich. On a cold December evening in 1963, I found myself at London’s Royal Festival Hall witnessing cello playing that jolted me into believing that I had to become a cellist myself. Within months, Rostropovich was back at the RFH for a series of nine concerts playing 30 different concertos in just four weeks and I made sure that I was in the front row for every one.

In his introduction to the series, Rostropovich wrote: ‘The cello has become, in our times, a tribune, an orator, a dramatic hero,’ a phrase that immediately struck a chord with me. It also served as an apt description of his own playing: he was the great dramatic orator, sometimes almost overpowering his audience with the force of his declamations while at other times bewitching it with the sweetest of whispered pianissimos. I had never heard (nor seen) cello playing like it. Technically, he was a marvel, sometimes accomplishing feats with his left hand that were almost impossible to understand. (Years later, I asked him about this and he replied, ‘Sometimes I couldn’t understand that either.’)

As he left the stage with tears streaming down his face, there was not one person in the audience left in any doubt where his sympathies lay. It was the most vivid example I have ever witnessed of the power of music over words.

In cello terms, Rostropovich was a colossus. Quite apart from his superlative playing, he looked to the future and inspired an unprecedented number of new works for his instrument. Bliss, Britten, Dutilleux, Khachaturian, Lutosławski, Penderecki, Piazzolla, Prokofiev, Schnittke, Shostakovich, Walton, James MacMillan and Arvo Pärt are among a multitude of composers who wrote for him. Surely it is impossible to name any other musician who has come near to matching his achievement in creating an entirely new repertoire for their instrument? But what convinced composers who, in some cases, had ignored previous pleas for a work for the cello?

In a similar spirit to Pablo Casals half a century earlier, Rostropovich altered perceptions of the cello. Although Britten had refused offers to compose for the instrument before, after hearing Rostropovich play Shostakovich’s new cello concerto (No 1), he immediately began work on a sonata. Completed and premiered less than a year later at the 1961 Aldeburgh Festival in Suffolk, it was the first of five major works Britten wrote for the cellist. And although it was Rostropovich who initially was badgering composers to write for his instrument, soon composers were forming a lengthy queue for his attentions. His effect on other cellists was galvanising too: from a purely technical perspective, they were forced to raise their game. (In the two recordings I have by another renowned cellist of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations, the first of which was made pre-Rostropovich, it is noticeable how much faster the final variation is in the later, post‑Rostropovich, version!)

Born on March 27, 1927, in Baku, Azerbaijan, Rostropovich was a comparative latecomer to the cello, only beginning lessons with his cellist father at around the age of nine. He came to prominence as a cellist in 1945 when he won the All-Union competition for young musicians in Moscow; he went on to win important competitions in Budapest and Prague. By 1950 he had premiered sonatas dedicated to him by Myaskovsky and Prokofiev, and by the mid-1950s he was one of a select group of Soviet instrumentalists who were regularly touring the West, including his musical partners the pianists Emil Gilels and Sviatoslav Richter and violinist David Oistrakh.

Perhaps the most extraordinary concert Rostropovich ever gave occurred on the night of August 21, 1968, at the Royal Albert Hall as part of the BBC Proms. It was the day after Soviet tanks had rolled into Prague to crush the lenient rule of Alexander Dubček, and, ironically, Rostropovich was scheduled to play the most famous Czech concerto of them all, the Dvořák, with the USSR State SO under chief conductor Evgeny Svetlanov. It was an extraordinary combination of circumstances, intensified for Rostropovich by his personal attachment to the city where he had won one of his earliest international prizes and met his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya.

Many people felt that the concert should have been cancelled, but it went ahead regardless, with protesters both inside and outside the hall. The tension was unbearable and no one who was in the audience that evening (myself included) will ever forget his extraordinary performance of the Dvořák. At the end, he snatched the score off Svetlanov’s stand and held it high above his head, demonstrating his love for both Dvořák’s music and for Czechoslovakia itself. As he left the stage with tears streaming down his face, there was not one person in the audience left in any doubt where his sympathies lay. It was the most vivid example I have ever witnessed of the power of music over words.

Two years later, Rostropovich’s dissent with the Soviet regime erupted with an ‘open letter’ to Pravda in defence of his friend the writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. It spelt the end of Rostropovich’s freedom to travel and the beginning of a torrid time when his dwindling number of Russian concerts were regularly cancelled, often on the same day. But musicians, statesmen and royalty all loved ‘Slava’, and when US Senator Edward Kennedy heard of his troubles he personally asked the Communist Party Secretary Leonid Brezhnev to intervene. Astoundingly, in 1974, Rostropovich was granted a two-year visa to ‘travel for artistic purposes’.

Arriving in London with little more than a suitcase, his cello and his dog, Pooks, Rostropovich quickly set about rebuilding his career with an ever greater emphasis on conducting. Within three years he was Music Director of Washington’s National SO and his whirlwind schedule of performances and recordings continued until shortly before his death in 2007.

It is often said that the cello is the nearest instrument to the human voice, and Slava made the cello ‘speak’ like no other. The secret lay not only in his phrasing but also in his tone. Rostropovich cajoled his audience through his cello, and its sound was filled with the breath of God.

Rostropovich: defining moments

•1927 – Born to musical family in Azerbaijan

Piano lessons with mother from age four; begins cello with father (a former Casals student) around age nine. 1930s: family moves to Moscow. 1940: first public performance, Saint-Saëns’s Concerto No 1

•1943 – Meets Shostakovich

Attends his orchestration class at Moscow Conservatory, aged 16

•1945 – A winning streak begins

Wins Moscow All-Union competition. Further victories: World Festival of Youth and Students, Budapest, 1949; Prague Spring International Music Competition, 1950 (Dvořák Cello Concerto)

•1949 – First of a lifetime of premieres

Performs Myaskovsky’s Cello Sonata No 2; heard by Prokofiev, who writes a cello sonata for him (premiered 1950)

•1955 – Meets and marries soprano Galina Vishnevskaya

They found Rostropovich Vishnevskaya Foundation in 1991

•1959 – Classic recording

Shostakovich Cello Concerto No 1, which he has recently premiered

•1968 – Unforgettable London concert

Plays Dvořák at the Proms, day after Soviet invasion of Prague

•1970 – Another act of bravery

Open letter in support of Alexander Solzhenitsyn causes authorities to withdraw freedom to perform and travel, until 1974

•1989 – Berlin Wall, November 11

Impromptu performance of Bach suites following fall of the wall

•1990 – Restoration of Soviet citizenship

Retains residences in several countries; dies Moscow, April 27, 2007

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today