The Art of Operetta

Richard Bratby

Friday, January 15, 2021

Richard Bratby discovers that operetta – traditionally considered the poor relation of operatic works – is deceptively difficult to pull off, requiring musicians to dig beneath its polished surface in order to express hidden emotional depths

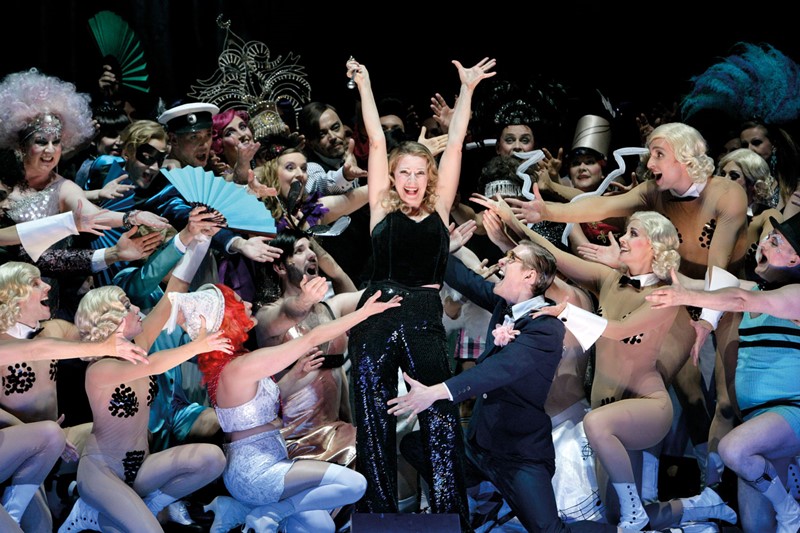

Photo: Dagmar Manzel dazzles in Barrie Kosky’s production of Abraham’s Ball im Savoy at the Komische Oper Berlin in 2013 (Iko Freese/Drama-Berlin.de)

The story of modern musical theatre hangs on a single phone call. Victor Léon and Leo Stein were quite clear about the best man to set their new operetta libretto for the Theater an der Wien: Richard Heuberger, composer of Der Opernball (1898). Their enthusiasm lasted until the day in spring 1905 when Heuberger played through his uninspired ideas for Act 1. Lehár – an infantry bandmaster turned aspiring operetta composer – was not the pair’s first choice of a replacement. Persuaded to give him a whirl, they sent him a copy of the libretto. That same night, Lehár phoned Léon, and down the line he played the Act 2 duet ‘Dummer, dummer Reitersmann’ – the first completed number of what would become Die lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow).

You probably already know what followed: the scepticism about Lehár’s score (‘That’s not music!’ declared the theatre’s director Wilhelm Karczag; he offered Lehár 5000 crowns to withdraw it) and the mixed reviews (Karl Kraus pronounced it ‘distasteful’) after it opened on December 30, 1905. And then the snowballing word-of-mouth success, and the opening of productions in Berlin, London and New York that transformed Léon and Stein’s phoned-in gamble into the most successful (and lucrative) property in the history of operetta. A Lehár-mad public could buy Merry Widow cigars, salads, corsets and perfumes. Richard Strauss was jealous; Mahler was a fan. ‘We danced together when we got home, and played Lehár’s waltz from memory,’ remembered Alma Mahler (the couple were ‘too highbrow’ to purchase the sheet music).

‘Escapism’ is the usual accusation – as if art has no business providing a joyous, if temporary, respite from an unhappy reality

And that’s just the start. Arguably (and in the story of operetta, fantasy can be as meaningful as fact), there’d have been no modern musical theatre without Lehár’s galvanising effect on Broadway and the West End; no MGM musicals without Mitteleuropean refugees who’d grown up dancing to the waltzes of Lehár and Kálmán; no global music industry without this dazzling proof that the right show could make you very rich indeed. Only the genre’s founder, Offenbach, and (in the English-speaking world, though certainly not confined to it) Gilbert and Sullivan come close to Lehár’s success. And in his own lifetime, none surpassed Lehár. The historian Richard Traubner, writing in 1983, estimated that The Merry Widow had received 250,000 performances worldwide in its first seven decades. In Lehár’s 150th anniversary year, it must be inching towards a cool half-million.

But can that really be right? In the UK, barring a couple of Widows, little was planned for the Lehár anniversary. These are lean days for operetta – driven from the stage by its descendant, the musical; from the airwaves by pop; and from the collective memory by a whole tangle of prejudices and (often false) assumptions about the form’s innate triviality. ‘Escapism’ is the usual accusation – as if art has no business providing a joyous, if temporary, respite from an unhappy reality. If 2020 has achieved anything positive in the arts, it might have gone some way to correcting that notion. When London’s Opera Holland Park managed to salvage something from the wreckage of its season, it began with a socially distanced operetta gala titled Heart’s Delight. Glyndebourne’s sole new production in 2020 was an exuberant, speedily assembled staging of Offenbach’s deliriously silly Mesdames de la Halle – the first Offenbach ever seen at the Sussex festival.

And it’s not as easy as they made it sound. The conductor John Wilson has said that The Merry Widow is the single most difficult thing he’s ever conducted. John Andrews, who conducted that Holland Park gala, has an operetta CV that runs from Offenbach’s Robinson Crusoé to what would have been a new staging of The Merry Widow this summer; he’s also recorded Cellier’s The Mountebanks and Sullivan’s Haddon Hall for Dutton. He agrees: ‘One of the big difficulties of operetta is trying to keep the bigger structure alive,’ he says. ‘At the most extreme end, in The Merry Widow, there’s more dialogue than music, so you’ve somehow got to keep the dialogue at a level of heightened drama out of which the music can come. It’s very, very difficult to go from a naturalistic delivery of the dialogue into a score as perfumed as The Merry Widow. And then you have this issue that it has to sound completely effortless. There’s as much rubato as Puccini, but no one’s supposed to notice. It’s fine for 19th-century grand opera to sound visceral; whereas with operetta, you have to expend all that effort on making sure that no one knows you’re working – and delivering it as if it’s the easiest thing in the world.’

That’s before you even get to the meaning behind it all. ‘In operetta, the depth of feeling is always underneath a veneer of sophistication and polish,’ says Andrews. ‘People don’t collapse on the floor or jump off buildings. So all that emotion is somehow expressed without politeness being sacrificed. It’s actually got a lot in common with Handel – that Baroque idea, where surface gentility is, in itself, expressing massive emotional depth.’

‘Comedy is a nightmare to direct, and it takes twice as long as an opera by Wagner or Mozart: it’s all timing’ – Barrie Kosky

And then, of course, someone actually has to sing it – and speak it, and act it. ‘Operetta calls for the same kind of singer as in opera,’ write Anastasia Belina and Derek B Scott, editors of The Cambridge Companion to Operetta (2020), before cheekily adding that, ‘The only difference is that the singer is also expected to act and dance skilfully.’ None of which comes as news to the soprano Soraya Mafi, who sang Teresa on Andrews’s recording of The Mountebanks. She’s currently preparing the title-role in Reynaldo Hahn’s delicious Ciboulette, but with a repertoire that embraces both Mabel in The Pirates of Penzance and Musetta (in ENO’s drive-in La bohème at Alexandra Palace, London, in September 2020), it’s clear that she – like many younger singers – sees operetta and opera as complementary skill sets. ‘It’s with the spoken dialogue that the difference really shows up,’ she says. ‘The thing is, when you’re doing spoken dialogue, you take control of the timing – the music doesn’t dictate it. Comic timing in operetta is so important.’

The physical act of delivering dialogue is a challenge in its own right, ‘especially when you’re doing it in a bigger theatre’, says Mafi. ‘I did Ida in Die Fledermaus as an undergraduate, and I found that I was struggling. As a soprano, you’re singing in a range that isn’t your spoken range. So I worked with a speech therapist, because if you’ve got a lot of dialogue and you’re supporting it to the level at which you support your singing, you’re going to be exhausted after doing a matinee and an evening show.’

Photo: a chorus scene from Cal McCrystal’s new production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe staged at English National Opera in London in 2018 (Clive Barda / ArenaPal / ENO)

But all this commitment is worth it: because despite operetta’s reduced status in the wider musical world, the central masterpieces of the repertoire are in surprisingly good health. It’s often a question of local perspective. In their central European heartlands, the Viennese standards still get good box-office results: Operabase has recorded that in the 2018-19 season Puccini and Bernstein were the only 20th-century operatic composers whose works received more performances worldwide than The Merry Widow. Die Fledermaus received more productions than Aida or Il trovatore, and Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin outperformed anything by Janáček, Berg or Britten.

In the Gallic tradition, Offenbach’s bicentenary in 2019 reaffirmed the indestructible freshness of ‘the Mozart of the Champs-Élysées’ (I write from experience – it’s not often one reviews a 30-disc set of a single composer and comes out thirsty for more). As for Gilbert and Sullivan, a generation has grown up without memories of the old D’Oyly Carte company, and perhaps with fewer prejudices about what these works can be. Playful, inventive new productions of Patience, Ruddigore and many more are now the norm. I took an opera novice to Cal McCrystal’s dazzling 2018 staging of Iolanthe at English National Opera and he left convinced that Gilbert’s libretto had been updated (it hadn’t), so unerringly did the combination of music, words and drama hit the satirical bullseye.

Photo: Dagmar Manzel in Die Perlen der Cleopatra, 2016 (Iko Freese/Drama-Berlin.de)

One director who has embraced a very particular operetta tradition is Barrie Kosky. G&S was (and is) a vital presence in his native Australia; but his Hungarian grandmother instilled an early love of the central European classics too: ‘I saw Richard Bonynge conduct Kálmán’s Countess Maritza, and a dreadful production of The Merry Widow with Joan Sutherland in Melbourne. Appalling! Operetta was not Dame Joan’s fach – we can say that very confidently. But in my childhood, from recordings and anecdotes, I knew there was this thing called operetta, and that it wasn’t like Wagner or Mozart or Verdi or Puccini or Janáček. And I loved it.’

Since 2012, as Intendant of the Komische Oper Berlin, Kosky has been rediscovering the jazz operettas of inter-war Germany. Presented with show-stopping theatrical flair, works like Paul Abraham’s Ball im Savoy and Oscar Straus’s Die Perlen der Cleopatra have played to capacity houses – as Kosky and his company renew a lost repertoire along with the techniques required to make it work. ‘I was inventing a style as I was directing,’ he says. ‘I mean, I didn’t come to Ball im Savoy or La belle Hélène saying, “This is the style.” What you see here in Berlin is a style that has emerged organically out of the people that are doing it. Comedy is a nightmare to direct, and it takes twice as long as a Wagner or a Mozart opera: it’s all timing. And it’s also casting – you’ve got to find people who have that really wonderful mixture of intelligence, irony and the erotic. This goes for Lehár, it goes for Kálmán, it goes for Oscar Straus, and it goes for Offenbach. We know that, a lot of the time, the great operetta singers in the ’20s and ’30s didn’t sing the vocal line. They spoke the text, they shouted the text, they half-sung the text, they interjected.

‘It’s very easy to do it in Berlin, because there’s a huge context here. I’m doing it in the theatre where Lehár conducted and premiered The Land of Smiles (in 1929). Offenbach conducted his own operettas at the Deutsches Theater. The city has a huge operetta history, and we’ve tried to find a modern way of doing them, but not by rewriting, because that’s cheating. What we do is exactly like reconstructing a Baroque opera. We may use 70 per cent of the original text, and then improvise and make up 30 per cent, but the stories and the characters and the dialogue are mostly from the original – because most of the masterpieces are fabulous. And as you know, it’s been a spectacular success. You can’t get a seat.’

It’s also increasingly clear that the standard history of operetta – beginning with the sparkling, satirical ‘golden age’ of Offenbach, Sullivan and Johann Strauss II, followed by a post-Merry Widow ‘silver age’ that’s essentially a long decline into Ruritanian escapism (that word again) – won’t wash any more: if it ever did. What about Lehár’s later scores for the Austrian tenor Richard Tauber – shows like Paganini (1925), The Land of Smiles (Das Land des Lächelns) and Giuditta (1934), in which he adopts the exotic settings of inter-war cinema to tell stories of disillusion and loss? No champagne finales here. Abraham’s Viktoria und ihr Husar (1930), a drama of lives torn apart by the First World War and its aftermath, still finds space for chorus lines and red-hot saxes. In Die Herzogin von Chicago, Prince Sandor tries to outlaw the Charleston, but Kálmán’s sweeping score – complete with jazz band, gypsy ensemble, children’s chorus and full orchestra – gives Broadway a run for its money.

Photo: Three little maids (from left): Kitty Whately (Peep-Bo), Soraya Ma i (Yum-Yum) and Sioned Gwen Davies (Pitti-Sing) – 2019 revival of the 1987 Mikado by Jonathan Miller (Genevieve Gerling)

If you can’t get to Berlin, or to the Operettszínház in Budapest, or to the festivals in Mörbisch and Bad Ischl in Austria and in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, where rarities are revived and national traditions are celebrated each summer – well, it’s never been a better time to collect recordings. Dutton’s Haddon Hall has come coupled, brilliantly, with two contemporary 30-minute one-acters, recreating the experience of a whole night out at the Savoy Theatre in the early 1890s. The French independent label Bru Zane has given deluxe scholarly treatment to rarities by Offenbach as well as (even more encouraging) Messager’s Les p’tites Michu.

Meanwhile, CPO, with its long-running Lehár project (often taken from stagings at Bad Ischl), is one of several labels plugging the gaps in the Austro-German operetta discography. For the first time, scores like Kálmán’s Ein Herbstmanöver, Heuberger’s Der Opernball, Fall’s Die Dollarprinzessin and Künneke’s Herz über Bord are available, effectively complete, in serviceable modern recordings – though the performance style divides opinions, especially in the growing academic field of operetta studies. Interpretations can be over-earnest, and recordings routinely cut or omit librettos – unconsciously echoing the way the Third Reich erased the work of so many Jewish operetta creators. For Kosky, the deluxe, grand opera approach to operetta has malign roots. ‘The Nazis Aryanised it – they took the jazz out, they took the sex out, they took all the danger out, they took all the wit out, they reorchestrated it. Then, after the war, opera singers decided that it was nice to have a holiday and make some money by doing an operetta album, and they put the last nail in the coffin. What operetta needs is the same revolution that happened in Baroque music a few decades ago. I mean, listen to the way Tauber sings operetta – so spectacularly good; but listen to Jonas Kaufmann trying to do the same music and it’s a disaster. I love Nicolai Gedda singing French and Italian opera, but his recordings of operetta are catastrophic, like Elisabeth Schwarzkopf’s. I mean, it’s like getting Emma Kirkby to sing Wagner.’

Ouch. True, I didn’t buy Kaufmann as a latter-day Tauber, but I came to Lehár through Schwarzkopf and I can’t be alone in having a guilty soft spot for all those overblown post-war German recordings – after all, for many years they were the only game in town. And operetta, like jazz, has always adapted, taking on the colouring of its cultural surroundings. For every aficionado who winces at an overproduced 1970s studio recording (I’ve got a Der Graf von Luxemburg that’s been reorchestrated with accordion and rhythm guitar), there’s someone for whom that recording has been a cherished pathway into a happier world. Operetta revivals can be a necessary act of cultural restitution, but they succeed, in the end, because these are fascinating, moving, and infinitely renewable works of art that continue to speak to audiences on all sorts of levels.

Not the least of these levels is pure entertainment. ‘People are happy to come and have three hours of emotion and spectacle and sex and fun, but with enormous virtuosity,’ says Kosky. ‘That’s one of the words that’s important to the success of operettas, from Offenbach onwards: virtuosity. It’s 10 times harder to direct a good Orpheus in the Underworld than it is to direct a good La traviata.’

For Mafi, operetta’s significance is intensely personal. ‘My dad passed away on New Year’s Eve, just before I was due to sing some Viennese concerts with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. I turned to the orchestra and said, “Guys, I just lost my dad, and this music brought him so much joy in his toughest times. To me, this is just as important as singing Mozart or Richard Strauss.” It’s really cathartic for me, this kind of music. It speaks to people.’

Or as another operetta fan, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, once put it: ‘Profundity must be hidden. Where? On the surface.’ Like no other musical form, operetta is a dazzlingly executed high-wire act thriving on the tension between words and music, artificiality and sincerity, sophistication and pure, uninhibited fun. For Andrews, that’s both the challenge and the reward: ‘In life, sentimentality and deep emotion sit right next to each other – because at our moments of emotional crisis we cling to familiar forms. And so it’s not false to resort to cliché, it’s actually very true – that when we’re at our weakest and our most vulnerable, Lehár says, “I’m not going to talk to you about all that. I’m going to sing you a folk song about two young lovers.” That’s “Vilja” (from The Merry Widow), and it’s everything that you need. And you can also have the dancers, and that great tune, and the audience within the play, and the real audience – and everyone still understands exactly what’s being said.’

Now, in Lehár’s 150th-birthday year, the techniques of operetta, its traditions and the whole culture that created it have changed beyond recognition. But its appeal is as potent – and as tuneful – as ever.

Recommended Recordings

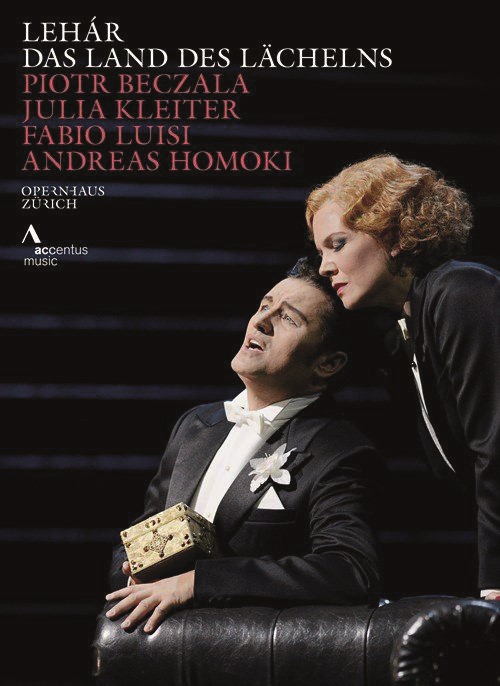

Lehár Das Land des Lächelns

Piotr Beczaa ten Zurich Opera / Fabio Luisi et al

Accentus

From the new school of operetta production, Andreas Homoki’s atmospheric art deco staging brings out the tragic side of Lehár’s cross-cultural love story.

☆

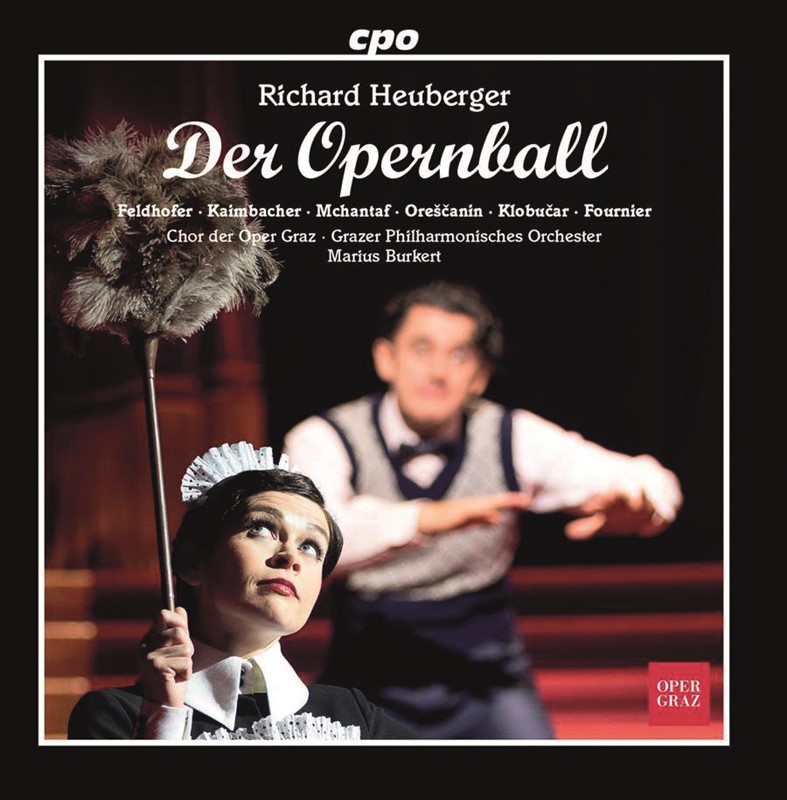

Heuberger Der Opernball

Gerhard Ernst bar Graz Opera / Marius Burkert et al

CPO

This gem from CPO’s ongoing operetta series is the first modern recording of Heuberger’s champagne-fuelled Viennese romcom. Zemlinsky helped with the orchestration.

☆

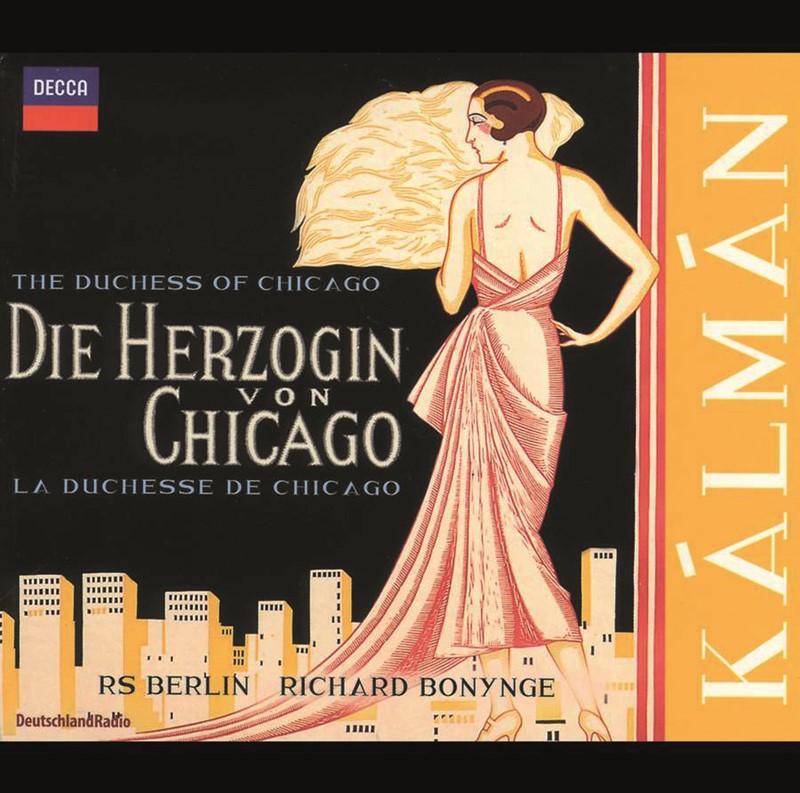

Kálmán Die Herzogin von Chicago

Endrik Wottrich ten Berlin Rad Chor & SO / Richard Bonynge et al

Decca

The Viennese tradition declares war on jazz in this sumptuous recording of Kálmán’s 1928 blockbuster – a landmark of historically informed operetta on disc.

☆

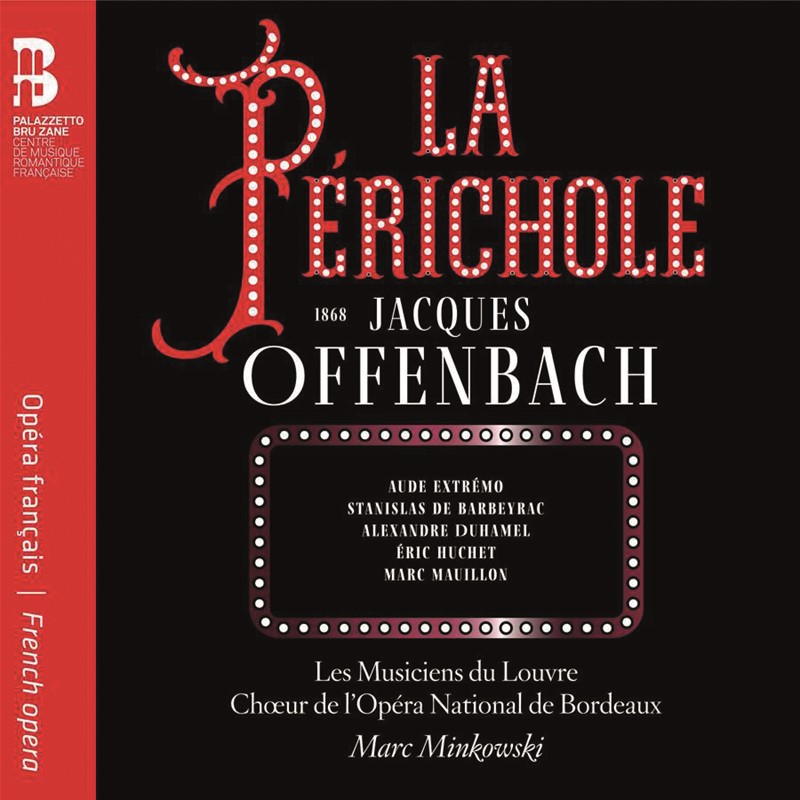

Offenbach La Périchole

Aude Extrémo mez Bordeaux Nat Op / Marc Minkowski et al

Bru Zane

Irreverence, sparkle and the unmistakable tang of Gallic wit are all there in Minkowski’s pioneering (and stylish) period-instrument account, taken from live performances.

☆

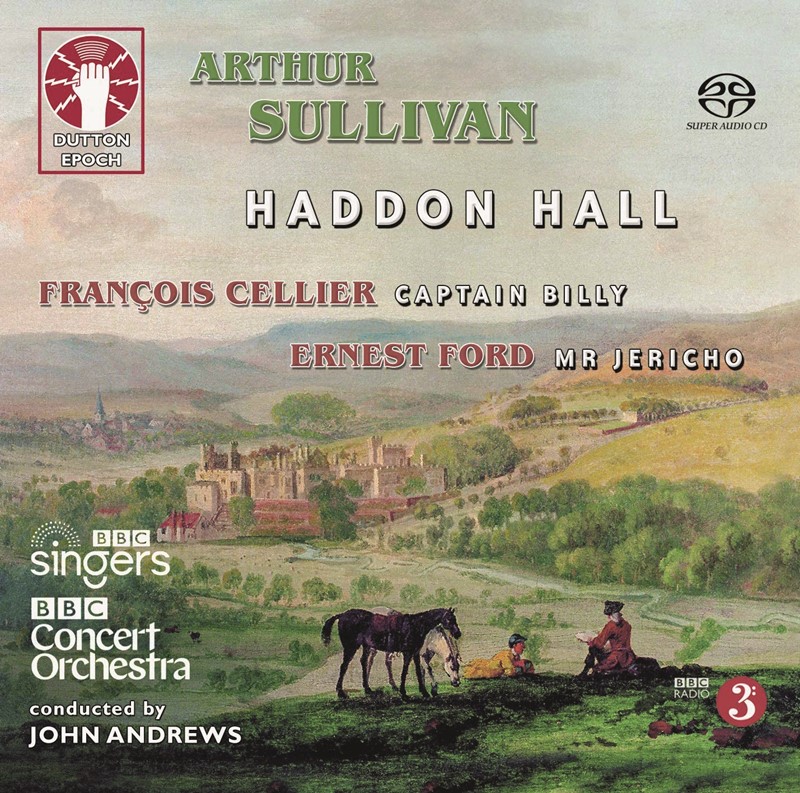

Sullivan Haddon Hall. Cellier Captain Billy. Ford Mr Jericho

Ed Lyon ten Ben McAteer bar Henry Waddington bass-bar BBC Singers & Concert Orch / John Andrews et al

Dutton

Sullivan without Gilbert is a warm-hearted delight, but the real discovery here is a pair of irresistibly hummable one-acters – a forgotten side of the Savoy tradition.

☆

This article originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe today!