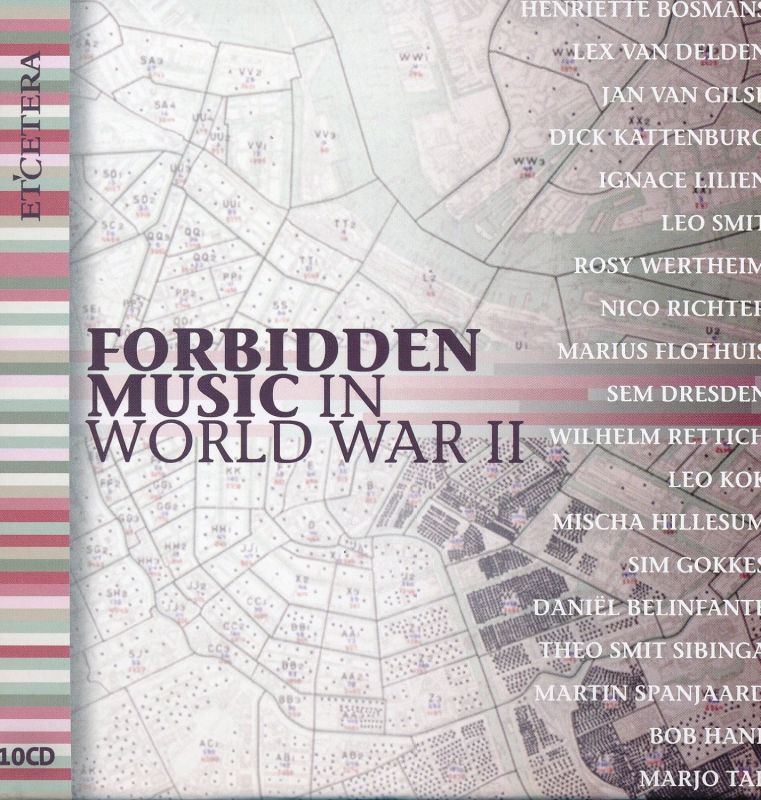

Forbidden Music in World War II

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Etcetera

Magazine Review Date: AW2015

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: KTC1530

Author: Tim Ashley

The facts are often horrific. Three out of every four Dutch Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, among them Leo Smit, the leading composer of the younger pre-war generation; Sim Gokkes, music director of Amsterdam’s Portuguese Synagogue; and Dick Kattenburg, aged 25, whose music remained unpublished in his lifetime. Jan van Gilse succumbed to pneumonia after his two sons, like himself resistance members, were executed. Nico Richter died of illness and injury sustained in Dachau, shortly after the camp’s liberation.

Throughout, the set testifies to the courage of those for whom music became an existential assertion of identity in the face of atrocity. Composer-pianist Henriëtte Bosmans and Rosy Wertheim – whose pre-war Paris salon was graced by Honegger, Milhaud and Messiaen – gave clandestine concerts in hiding when public performance of their work was forbidden. Resistance hero Lex van Delden, born Alexander Zwaap, became a leading post-war figure under the name he took as his wartime alias. Not all the composers were Dutch by birth: Ignace Lilien, who survived using false identity papers, was a Polish-Ukrainian refugee from the First World War.

Many of the works included pre-date or post-date the war, affording us major insights into musical life in the Netherlands between 1900 and the 1960s. Early-20th-century Dutch music is often described as conservatively anti-modernist, which proves untrue. The country’s neutrality in the First World War resulted, in fact, in a remarkable openness of influence, though, with the exception of Nico Richter, whose music veers towards atonal, Webernian compression, the impact of the Second Viennese School was minimal.

Ariadne auf Naxos looms large over van Gilse’s 1916 Nonet, beautifully played by the Viotta Ensemble and the Ebony Quartet. Others looked to France. Smit’s ballet Schemselnihar, based on Persian legend, owes much to Daphnis et Chloé, while his Cello Concertino is very Debussian: Ed Spanjaard, who lost members of his own family in the Holocaust, conducts lucid performances from 1993 and 1999 respectively, while the young Pieter Wispelwey is his admirable soloist.

Stravinskian neo-classicism and the jazz-inflected modernism of Les Six impacted elsewhere. Lilien, whose day job as a chemical engineer frequently took him to South America, outdoes Le Boeuf sur le toit with his fabulous Modern Times Sonata for violin and piano, engrossingly performed by Marijke van Kooten and Frans van Ruth. Van Delden’s sinewy orchestral textures have a strong Stravinskian tang, his post-war status reflected in a clutch of Concertgebouw broadcasts from the 1950s and ’60s conducted by Jochum, Szell and Haitink.

One striking aspect is the equality accorded women composers in pre-war Netherlands, unique in Europe at the time, one suspects. Wertheim’s music, its fluctuating tonal centres curiously reminiscent of Delius, is an acquired taste, though Bosmans, openly bisexual and often uninhibited in expression, is utterly remarkable. Her Cello Sonata, written in 1919 for her cellist lover Frieda Belinfante, is a tremendous work, superbly played here by Doris Hochscheid, with Frans van Ruth again at the piano.

The set includes a great deal of chamber music. Many wartime works, written and sometimes performed in almost unspeakable circumstances, were, of necessity, both small-scale and short. Many were also rediscovered by the set’s curator, the flautist Eleonore Pameijer, Artistic Director of the Leo Smit Foundation, set up in 1996 to research the work of all the composers included here. It is to Pameijer that we owe our awareness, above all, of Kattenburg’s sad brilliance after his manuscripts were given into her keeping by his surviving family, and of the flautist Ima van Esso, for whom much of his work was written: van Esso was interned with him in Auschwitz, and survived. The sincerity of Pameijer’s playing impresses and moves throughout.

There are occasional omissions, most notably Lilien’s 1943 De Ballade van Westerbork, bravely bearing witness to the concentration camp in the north east Netherlands, where many, Smit and Kattenburg among them, were held before transportation to the death camps in the east. I should also have liked to hear some of Bosmans’s late songs, written for the last of her partners, the French soprano Noémi Pérugia. The booklet-notes are overly brief and you need to look up the composers’ biographies on the Leo Smit Foundation website. But this is a major issue nonetheless. It breaks your heart, and opens minds and ears to much we haven’t encountered before. Outstanding.

Explore the world’s largest classical music catalogue on Apple Music Classical.

Included with an Apple Music subscription. Download now.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.