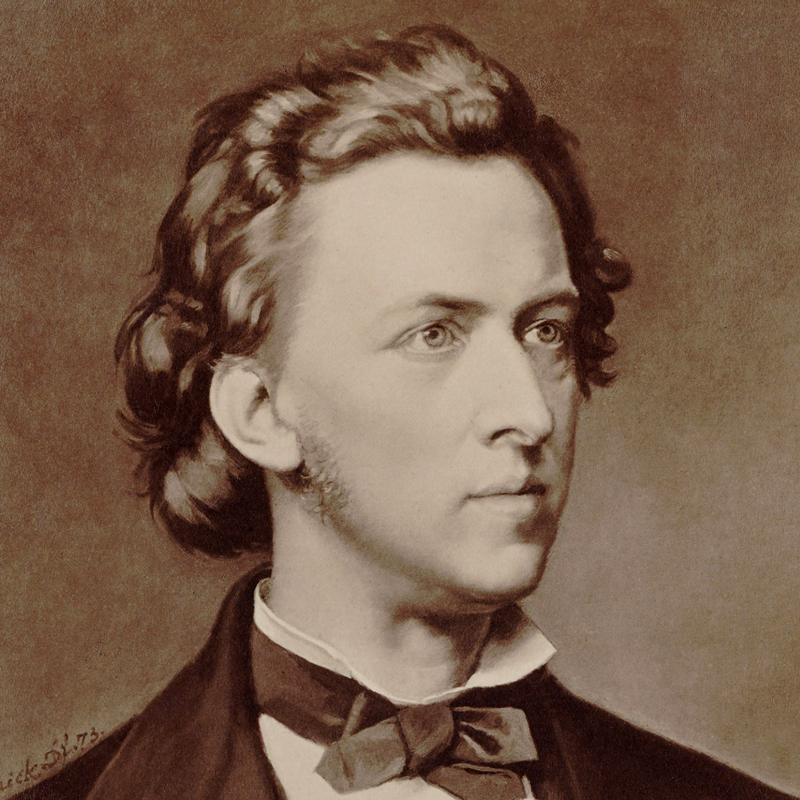

Chopin

Born: 1810

Died: 1849

Fryderyk Chopin

Few composers command such universal love as Chopin; even fewer still have such a high proportion of their entire output remaining in the active repertoire.

He’s the only great composer whose every work involves the piano – no symphonies, operas or choral works and only a handful of compositions that involve other instruments. He wrote just under 200 works; 169 of these are for solo piano.

See also: 50 of the greatest classical pianists on record

Explore Chopin's life and music...

The 10 greatest Chopin pianists

Stephen Plaistow recalls the illustrious recorded history of Chopin's oeuvre and offers a personal view of great Chopin interpreters... Read more

Arthur Rubinstein – the greatest Chopin pianist on record?

Bryce Morrison recalls the flawless combination of Slavic passion and Gallic precision in this charismatic ‘singer’ pianist, who conducted a lifelong love affair with his audiences... Read more

The 50 greatest Chopin recordings

Complete with the original Gramophone reviews of 50 of the finest Chopin recordings available... Read more

Podcast: Jan Lisiecki on Chopin's Nocturnes

The Canadian pianist talks about his Polish heritage and his relationship with Chopin's 21 miniatures...

Fryderyk Chopin: A Biography

The greatest of all Polish composers had a French father, Nicholas, who had gone to Poland as a young man and become a tutor to the family of Countess Skarbek at Żelazowa Wola.

His mother was the Countess’s lady-in-waiting, herself from Polish nobility.

This duel nationality is reflected in Chopin’s music – the epic struggle of the Poles and the refined elegance of the French.

Shortly after Fryderyk’s birth, the family moved to Warsaw where his father had a teaching post.

First piano lessons

Chopin had his first piano lessons from Adalbert Żywny in 1816, a local all-round musician, and made his public debut at nine.

He then became a piano student of Joseph Elsner, director of the Warsaw Conservatory.

It’s largely thanks to Elsner and Żywny that Chopin developed into the original creative force he became: they let him develop in his own way.

First public performances

A friend of Chopin’s father invited him to Berlin and in 1829 he gave two concerts in Vienna, including his Variations on Mozart’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’, after which Schumann made his famous judgement: ‘Hats off, gentlemen! A genius.’

The fading attractions of Warsaw, further diminished by his unrequited love of a young singer, persuaded him to leave Poland.

Before he left, his old teacher Elsner presented him with a silver urn of Polish earth with the admonishment ‘May you never forget your native land wherever you go, nor cease to love it with a warm and faithful heart’.

The urn was buried with Chopin when he died.

Chopin in Paris

Despite a Polish revolt against Russian rule soon afterwards, Chopin headed for Vienna (probably he would have been too physically frail to serve in the army in any case).

After some time in Stuttgart, intending to travel to London, he stopped off in Paris in 1831.

It remained his home for the rest of his life.

His Paris debut in January 1832 was not a success.

The Parisians did not take to his playing or music immediately and Chopin thought for a time of leaving for America.

His destiny was changed by Prince Radziwiłł who introduced him to the salon of Baron Jacques de Rothschild.

Finding the right audience

Here Chopin triumphed and from then on his career as a composer (and highly paid teacher) was a story of unbroken success.

Chopin was a sensitive, fastidious man who never enjoyed exactly robust health.

The rich, privileged world of the aristocratic and wealthy salons not only appealed to his snobbish instincts (he liked to mingle with money and beautiful women) but provided the perfect ambience for his music and his particular style of playing. Audiences admired his cantabile (singing) touch.

Chopin vs Liszt

Where Liszt was the thunderous, virtuoso showman, Chopin was the refined, undemonstrative poet, noted for his rubato, the effect whereby notes are not played in strict tempo but subtly lengthened and shortened ‘like a trees’ leaves in the breeze’, as Liszt described it.

George Sand

His first great love in Paris was the flirtatious daughter of Count Wodzińska. The family put a stop to the affair.

His next was perhaps the most unlikely woman of his circle: Aurore Dupin (Mme Dudevant), the radical, free-thinking novelist who called herself George Sand.

By no means good-looking (photographs bear witness), she smoked cigars and wore men’s clothing.

‘What a repellent woman she is,’ was Chopin’s reaction when he first set eyes on her. ‘Is she really a woman? I’m ready to doubt it.’

Nevertheless she exercised a fascination for Chopin and a relationship developed which lasted for 10 years, a mother figure who became the love of his life.

One of her personal letters implies that the physical side of their life was embraced less than enthusiastically by the composer.

Disaster in Majorca

In 1838 George Sand travelled to Majorca with her son and daughter, and Chopin joined her there.

Instead of the paradise they hoped for, it turned into a disaster with inhospitable and antagonistic locals, damp, wet weather and the breakdown of Chopin’s health.

He began having haemorrhages and hallucinations, and it was only a prompt departure for the mainland that saved his life (he had another haemorrhage in Barcelona).

The height of his powers

For the next few years, Chopin was at the height of his creative powers, respected and internationally famous.

His health deteriorated and he became more consumptive year by year.

The increasingly tense relationship with George Sand came to an end in 1848.

Sand seemed comparatively unaffected; ‘Chopin,’ said Liszt, ‘felt and often repeated that in breaking this long affection, this powerful bond, he had broken his life.’

A Scottish pupil of Chopin, Jane Stirling, persuaded him to make a trip to England and Scotland with her but this and a few fundraising concerts undermined his health further and when he returned to Paris he became a virtual recluse, too weak to compose or teach.

He gave strict instructions that all his unpublished manuscripts be destroyed.

Chopin had a good idea of his worth and was determined that only his best work should survive.

He died on October 17, 1849, from consumption and was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery next to his friend Bellini.

Chopin's legacy

More than any other, Chopin is responsible for the development of modern piano technique and style.

His influence on succeeding generations of writers of piano music was profound and inescapable.

He dreamt up a whole range of new colours, harmonies and means of expression in which he exploited every facet of the new developments in piano construction.

The larger keyboard (seven octaves) and improved mechanism opened up new possibilities of musical expression.

He possessed an altogether richer and deeper poetic insight than the myriad pianist-composers who flourished during his lifetime.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.