Andrew Parrott on The Taverner Consort at 50: ‘It’s not that I believe in perfection. I think that could be very boring’

Rebecca Tavener

Thursday, May 25, 2023

The Taverner Consort, Choir & Players were among the first pioneers in the modern age to perform early music. Its founder Andrew Parrott is still driven by an urge to push boundaries

What was it in the air of the 1970s that gave birth to some of the great early music organisations, now celebrating major anniversaries? 2023 finds The Taverner Consort, Choir & Players reaching their half-century, something that crept up on the group’s founder Andrew Parrott: ‘I only realised very recently. We did the calculation just a few months ago, and thought we’d want to do something special.’ ‘Something special’ is an understatement when one looks at the book The Pursuit of Musick (see review, p.64), and there’s more – read on.

Going back to the beginning, Taverner was founded in 1973 in May, in preparation for the Bath International Music Festival. Since then, it has toured extensively in the UK, Europe and further afield (including the USA and Japan). The ensemble is best-known for its pioneering recordings, including John Taverner’s Western Wind Mass (2016) which won a Gramophone award; it also attracted a Diapason d’Or in 2017. In the liner notes, the ensemble describes itself as ‘a chameleon-like performing body’ – a perfect way to view so flexible a set-up, with the Choir, Consort & Players constantly forming and re-forming with different forces. Many stellar names in the field of early music have been associated with Taverner, including singers Emma Kirkby, Emily Van Evera, Evelyn Tubb, and Rogers Covey-Crump.

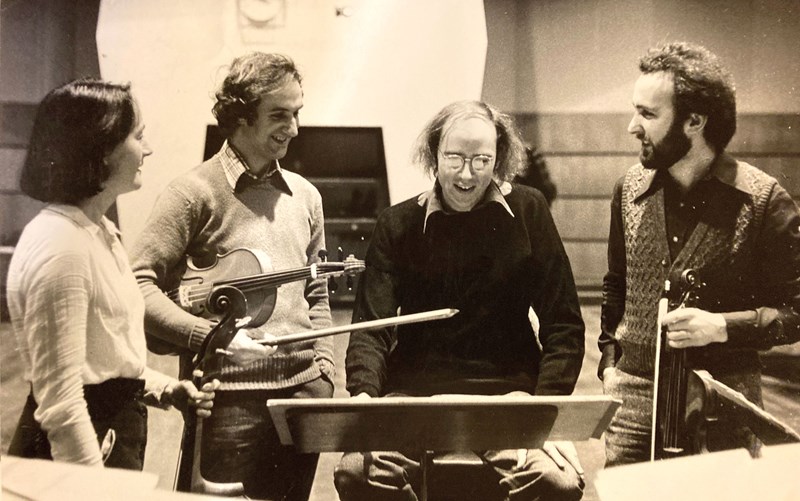

Jennifer Ward Clarke, Trevor Jones, Andrew Parrott and John Holloway in 1979 (courtesy Taverner)

In his introduction to The Pursuit of Musick Parrott writes of the joy of childhood musical discovery through an early gift from his parents, The Oxford Companion to Music (Percy A. Scholes). But what inspired him to become an early music specialist? Parrott unhesitatingly goes back to his studies in Oxford: ‘One of my tutors stood out – Frank L.L. Harrison, who was the first medieval specialist to transcribe the Eton Choir Book, and wrote the book, still a standard, Music in Medieval Britain.’

First and foremost a musicologist, there’s nothing of the diva about Parrott, an affable maestro continually searching for fresh approaches and greater insights into historically informed performance. Past discoveries, however satisfying, are trumped by the drive to explore and push the boundaries still further.

The febrile, pioneering spirit of the 1970s which saw a revolution in early music activity begat a massive outpouring of interest from amateur singers and players, following that pied piper, David Munrow – people who then become the consumers of professional events and recordings, an audience for ensembles like Taverner. As Parrott says: ‘What David Munrow was doing in terms of popularising was important, but equally important was Musica Reservata’. (This latter ensemble was founded in the 1950s by Michael Morrow who, among other startling ideas, used iconography as a guide for vocal production in his search for ‘authenticity’.) The calm and reasonable term ‘historically informed performance’ has replaced that oft-misunderstood and maligned ‘A-word’. Parrott thinks, ‘There was a silly authenticity debate, which presumed that we had said, “There is a performance that we can reconstruct,” and that was nonsense. People were using this language rather simplistically, but it’s really a principle which I would stand by for any music if we’re going to be bothered with it. We should take it as seriously as possible. Not in an overly solemn way, but to try to realise what it was about before we make any necessary compromises.’

There are over 60 Taverner recordings to date and while Parrott is always looking forward, he agrees that Monteverdi’s Vespers (1983) and J.S. Bach’s Mass in B minor (1984) were ground-breaking successes, in both cases making a massive impact in performance practice terms. Associate director of Taverner for 20 years, the musicologist and producer Malcolm Bruno says, ‘Taverner was distinct among its revivals for the musicological research alongside each performance and recording. Andrew became well-known and controversial with his research, particularly on Monteverdi and Bach. My 20 years at the helm in Taverner were certainly a heyday, leaving an indelible mark on my musical life and career!’ He is keen to enumerate their recorded achievements, from Machaut to Bach via Tallis and Gabrieli, and also lauds the self-sacrificial way in which Parrott ensured that really important projects such as the Florentine Intermedi of 1589 were recorded (1987, under the title Una Stravaganza dei Medici).

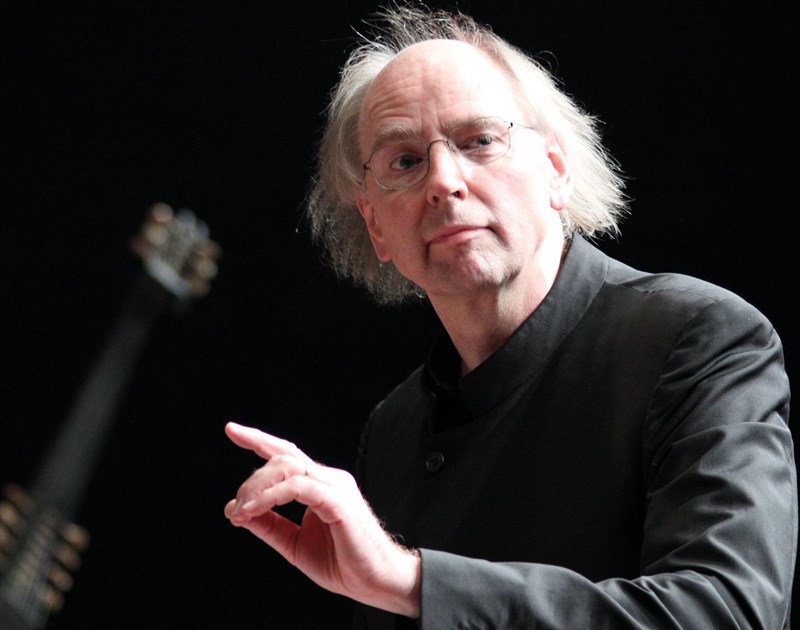

Andrew Parrott

Recordings are only snapshots in time, however, and Parrott is striving always for ‘better’: ‘It’s not that I believe in perfection. I think that could be very boring. I mean the principle of trying to get things right. So ambitious things like the Florentine Intermedi were, necessarily, experimental. I’m pleased with having done it; I would probably come back to many of the things that I’ve done and think, “Well, it was not bad for the times, but I could do much better now or differently.”’ Each Taverner recording has a zesty freshness about it, evocative of embarkation for new musicological shores: ‘It was necessarily experimental and fresh when we recorded the B minor Mass, because we were exploring that piece with period instruments, really for the first time, and with a vocal force including the boys of the Tölzer Knabenchor.’

Parrott doesn’t listen to Taverner recordings, ‘partly because I may be performing the same pieces again, and I don’t want to repeat myself. I like forgetting and starting with the, perhaps, better knowledge of certain things, and [having had] more experiences, and with a fresh team of people, because there are new people coming up all the time. Putting them together in different combinations means that they are more reactive.’

One of the great benefits of being an established star is that you don’t have to worry about what people think of you anymore (if one ever did): ‘I just sit here, or whatever, and do my thing, and hope that some people appreciate it.’

A question, perhaps unanswerable, is: has early music emerged from the ghetto? Parrott is ambivalent: ‘It’s great that it isn’t ghettoised, but that brings with it the fact that it’s commercially an entity just like everything else’. He wonders whether the classical canon of ‘great’ composers may work to the exclusion of little-known musical masters of the past. The experience of receiving a Gramophone award might be seen as symbolic: the pecking order in the ceremony has early music near the start, after emerging artists, and builds to the big names in ‘standard’ chamber, symphonic, operatic repertoire, etc.

Parrott will make two special recordings to mark the 50th anniversary: ‘I’ve chosen two pieces which evolved from the root musicological research that I like. They wouldn’t fit into concert programmes, and they’re too expensive individually to tour around. That’s where I can do something distinctive. I feel very disappointed often about the gulf that lies between musicology and performance. So if I’m going to continue for as long as I can, and enjoying it, then what I can do distinctively is to bring these two things as closely as possible together; so the book, I hope, will appeal to non-specialists, amateurs, and – particularly part three, I think – to performers.’

These two recordings will be released online at the end of May. Details of the first can be found in The Pursuit of Musick with a 1618 account from Praetorius on hearing Wert’s Egressus Jesus with an unusually lavish instrumentation: ‘I once heard the heartfelt and utterly beautiful motet Egressus Jesus (a7) by the excellent composer Giaches de Wert performed by 2 theorbos, 3 lutes, 2 citterns, 4 harpsichords and spinets, 7 viols, 2 flutes, 2 boys, an alto and a big viol without organ or regal. This produces an excellently sumptuous and glorious sound, such that almost everything in the church crackled with the sound of the many strings.’

The second track is one of Bach’s plangent pieces of Trauermusik. Scored for brass, singers and organ, O Jesu Christ, meins Lebens Licht, BWV 118, will be recorded with different instruments for the ‘litui’ (a mysterious instrument occasionally specified by Bach about which there has been much speculation) than those hitherto employed. Parrott believes his choice – after considerable research into the subject – to be an accurate instrumentation which hasn’t been recorded before. Both of these recordings promise delicious sonorities and intense musical experiences.

Reflecting on what has been and still keenly seeking new horizons, Parrott feels fortunate and speaks with characteristic modesty: ‘I certainly never planned a career in music and didn’t know what a career in music meant; I’ve been very lucky, I must admit, being able to make it work somehow.’

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of Choir & Organ. Never miss an issue – subscribe today