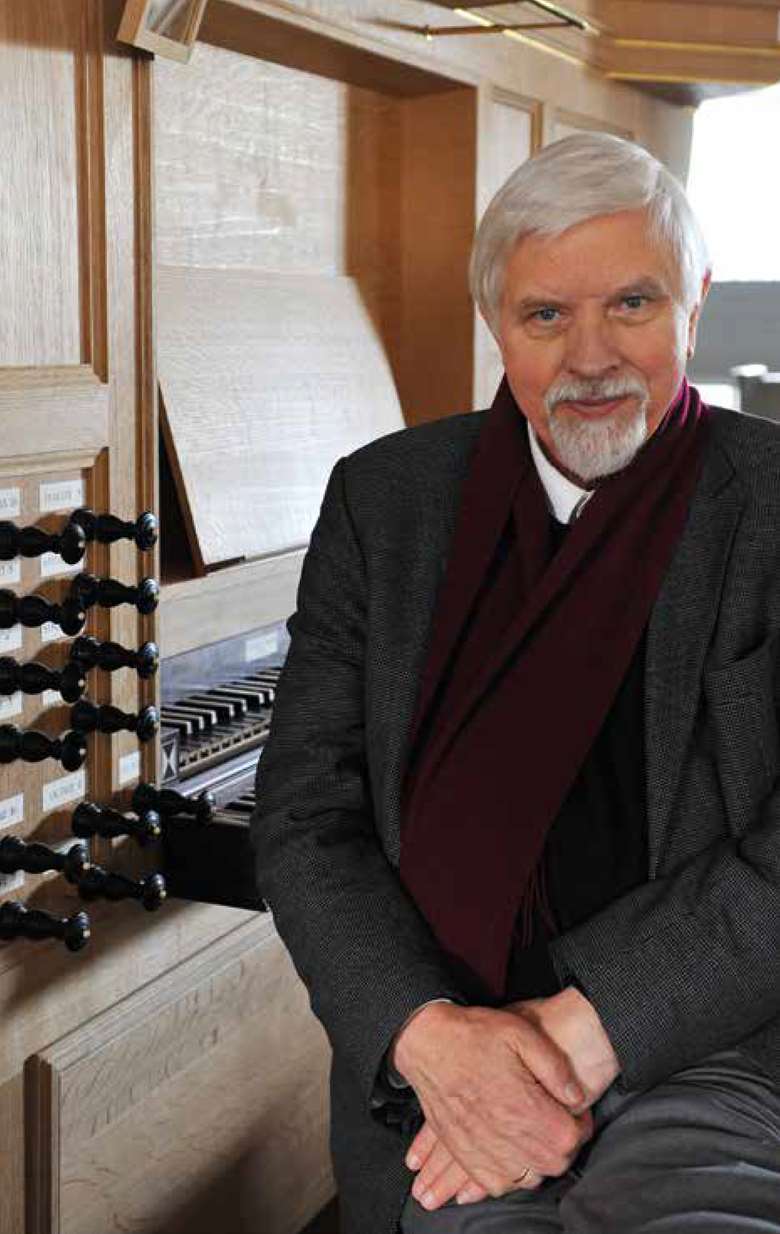

Harald Vogel: the scholarly pioneer

Matthew Provost

Sunday, April 2, 2023

Renowned organist and musicologist Harald Vogel shares his continuing research into the historic organs and music of north Germany with Matthew Provost

COURTESY HARALD VOGEL

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Choir & Organ. Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the choir and organ worlds. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Newly-commissioned sheet music to download from our New Music series

- Unlimited access to Choir & Organ's news pages

- Monthly newsletter