Bird's eye view | Interview with Marc Scora

Andrew Farach-Colton

Thursday, April 24, 2025

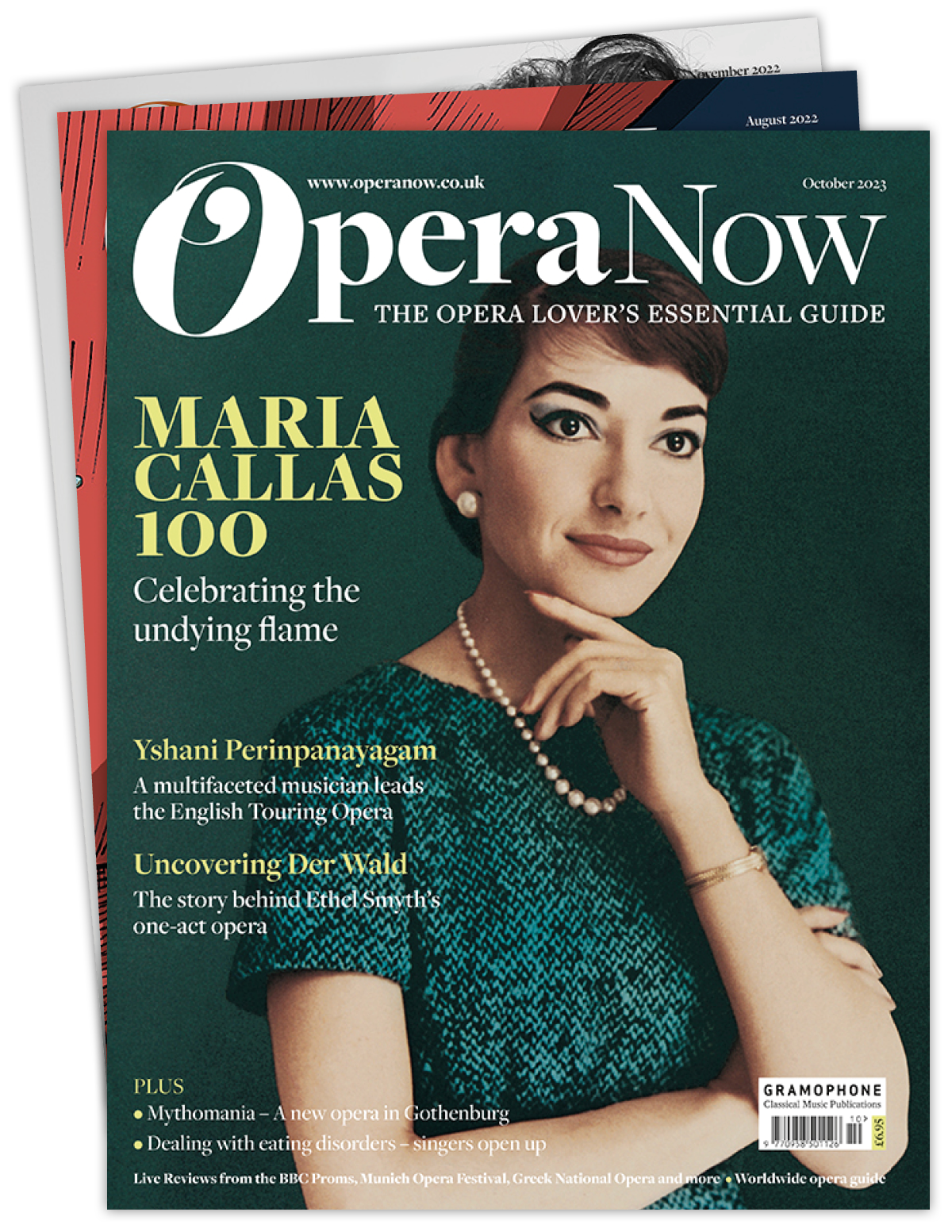

After 35 years at the helm of Opera America, Marc A Scorca is stepping down. From the rise of new American opera to championing diverse voices, he reflects on the past, present, and future of the art form and why creative renewal is essential to opera’s survival

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter