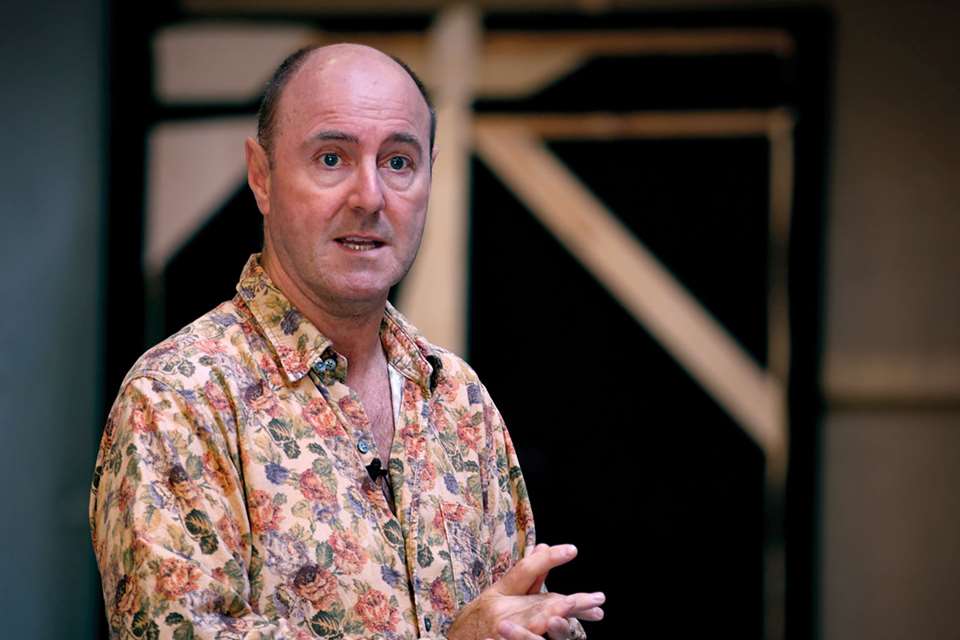

English Touring Opera's Robin Norton-Hale: ‘If you don’t get any letters, that means people thought, “That was all right” – I’d rather they felt something’

Thursday, April 4, 2024

General director of English Touring Opera, Robin Norton-Hale discusses her sanguine drive to present ambitious performances in the current opera climate

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter