John Adams and the creation of Antony and Cleopatra

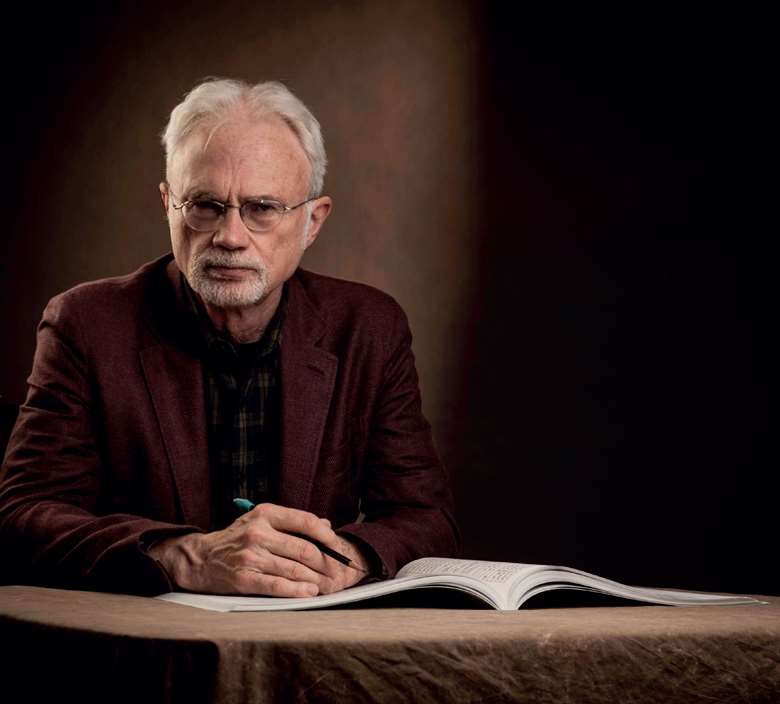

Thomas May

Friday, September 2, 2022

Five years and a pandemic after his last work for the stage, John Adams returns to opera with the Shakespeare-inspired Antony and Cleopatra, commissioned by San Francisco Opera and receiving its world premiere there this month

VERN EVANS

Register now to continue reading

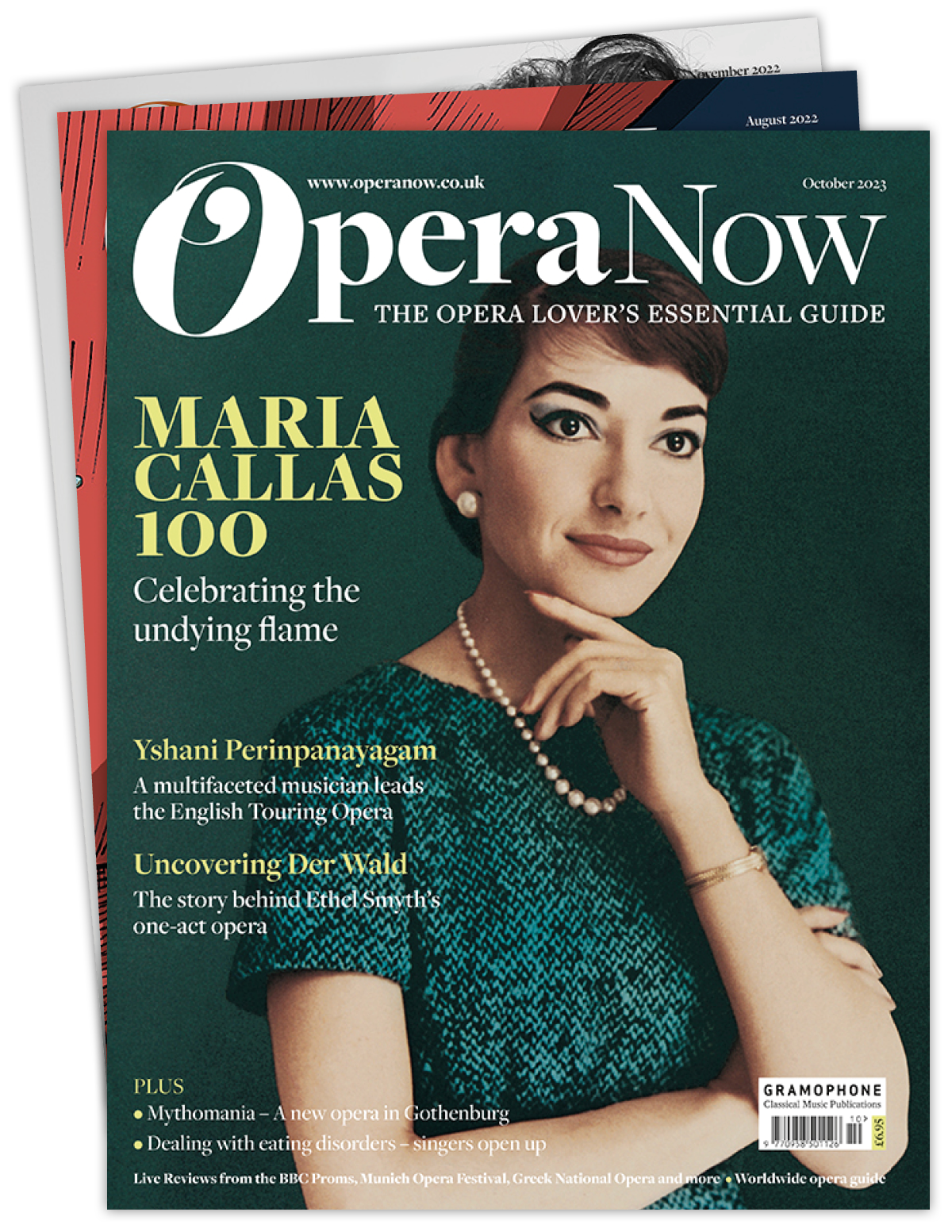

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter