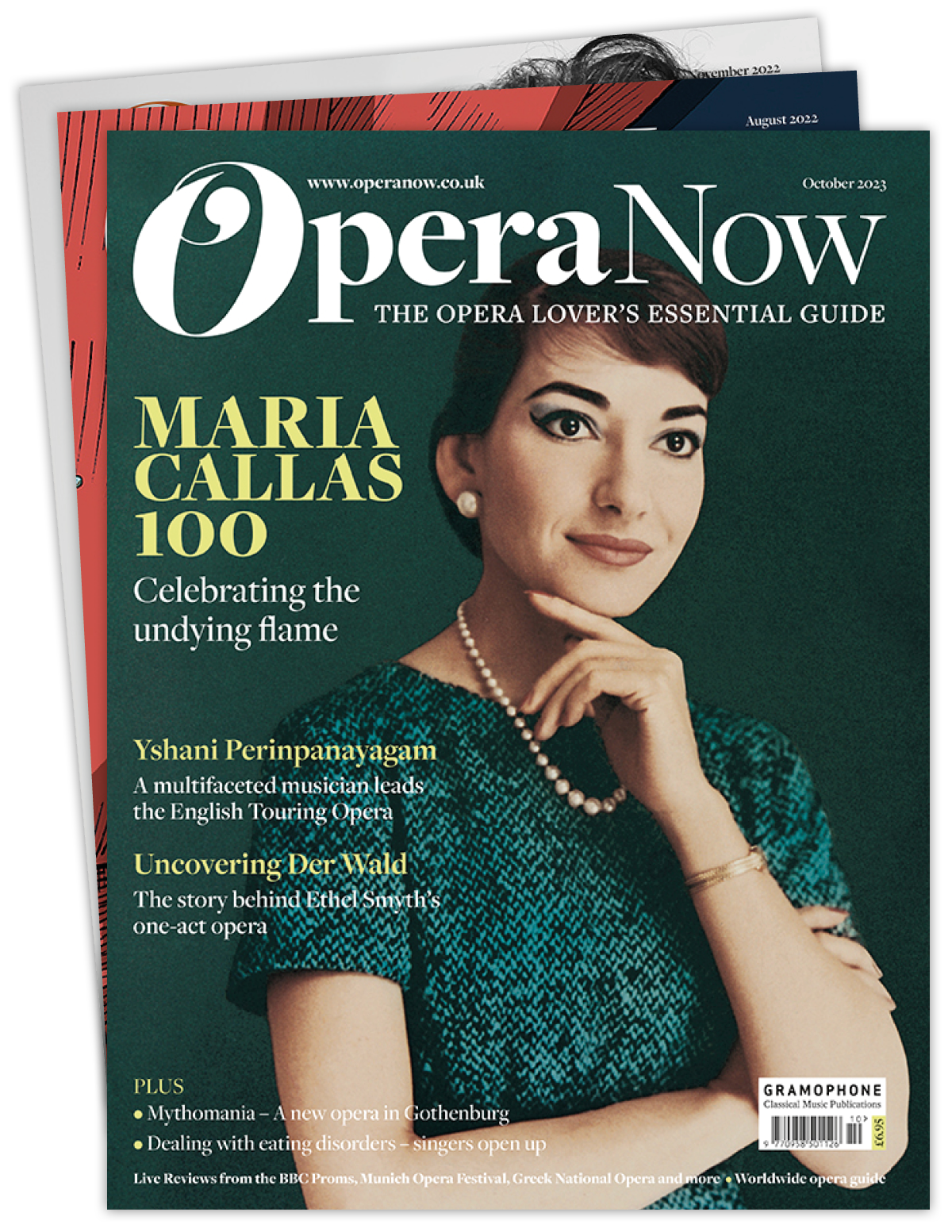

'In Europe, the industry treats "contemporary opera" as a problem' | Bill Bankes-Jones

Bill Bankes-Jones

Tuesday, August 29, 2023

Contemporary opera company Tête à Tête's Artistic Director on the future of new opera

Hugo Glendinning

Donkey’s years ago I joined ENO on the crest of its wave as a staff director. I came from the spoken theatre, already experienced in developing new writing. I was lucky to work on a series of great new works, though at the same time surprised that this new writing was not developed, so much as handed in and put on unquestioningly. There was no process. Composers, often with little experience of stage work, were left to their own devices and even tiny cuts were unthinkable.

There were comparatively few opera companies then. Unlike the pyramidal structure of theatre, where the National, RSC and West End stand on the shoulders of the Royal Court, Almeida, nationwide network of excellent rep theatres, all in turn fed by pub theatre. ubiquitous student theatre and true fringe, our mighty opera companies had no such robust support from their own sector.

Major drivers for me in building Tête à Tête, therefore, were to work towards a really strong, foundational fringe for opera, and to support composers by bringing them in to theatres from an early stage in their careers. I also had wonderful experiences working with director Declan Donnellan, who even in the 90s was making really inclusive companies to stage work, and felt very strongly we needed a parallel inclusivity in opera, in casting, creative, core team and audiences to keep this inspirational art form alive by connecting with anyone.

I’m very happy and proud to say all these things have happened, that there is now a thriving fringe for opera and also several hundred composers who’ve created stage works early on in their careers, and that we’ve worked with a wonderfully diverse range of artists and audiences through TàT’s 25 years.

The surprises are that, while we are feeding the great houses with skills – for example recent artistic directors of both the Royal Opera and ENO made shows in our festival, while Scottish Opera’s Music Director was previously TàT’s Music Director – this intake is not mirrored among composers or real commitment to inclusivity. The latter has led to a crisis in our bigger, subsidised opera companies.

Attending various opera events in Europe and the USA, I’ve learned that the bifurcation of the sector is a worldwide phenomenon, not just unique to the UK. Everywhere, the larger companies are committing to ever grander, glitzier productions now reaching wider and wider audiences via cinema relays and recordings. Costs sky-rocket and risk is ever more shunned. Meanwhile, artists are at the same time looking to smaller theatres to explore what they really care about, hone their skills and forge a deeper connection with their audiences on the fringe.

If opera as we know it is to survive, it urgently needs to learn to speak to everyone

While the core repertoire, mostly stories of women abused by men and often with a distasteful exoticism or archaic social background, mitigates against a genuine inclusivity, it’s nevertheless the commercial lifeblood of high-end opera. This is a choice made over decades, as European companies have consistently avoided refreshing the repertoire by nurturing audiences for new work.

The USA has a lot to teach us. From the mid-80s, Opera America has driven a determined movement to create a truly American canon. This has been embraced by audiences and opera houses alike, reflecting their young nation in all its colours and dominating the world. So we have Nixon in China, hugely popular works by Philip Glass, operas about Martin Luther King and Steve Jobs, pieces that ticket-buyers can understand and then enjoy. This has been so successful that, at a guess, nine out of ten new operas staged by English National Opera over the last two decades has, ironically, been American.

Here in Europe, the industry, treats ‘contemporary opera’ as a problem, lowers ticket prices as if to say that you’re in for a grim but improving evening. I recently went to see the play A Little Life in a packed theatre, most of the audience paying a fortune for tickets. No one called it ‘contemporary theatre’. It was thriving, urgent work, refreshing the audience and the repertoire, part of a large, steady and very normal stream of popular new works.

Happily, with TàT we’ve staged new, sometimes very challenging opera in every context possible; on streets, shopping centres, pubs, office atriums as well as theatres, with thousands of passers-by delighted to engage partly because no one has told them what they’re seeing is difficult, and nor are these works engulfed by alienating ritual.

If opera as we know it is to survive, it urgently needs to learn to speak to everyone. Like legitimate theatre, we need to splice the stories of yesteryear with popular new work that keeps refreshing the repertoire with stories of our time. And we need to work together as one if we are to redirect this vast vessel towards a bright future. Here’s hoping we do.

Tête à Tête: The Opera Festival runs at The Cockpit, Woolwich Works and online from 29 August – 16 September 2023 | www.tete-a-tete.org.uk

The Tête à Tête team

The Tête à Tête team