Adams: Antony and Cleopatra at Metropolitan Opera | Live Review

Thomas May

Thursday, May 15, 2025

Adams demands close attention and rewards it not with obvious operatic tropes, but with a cumulative and subtle psychological impact

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

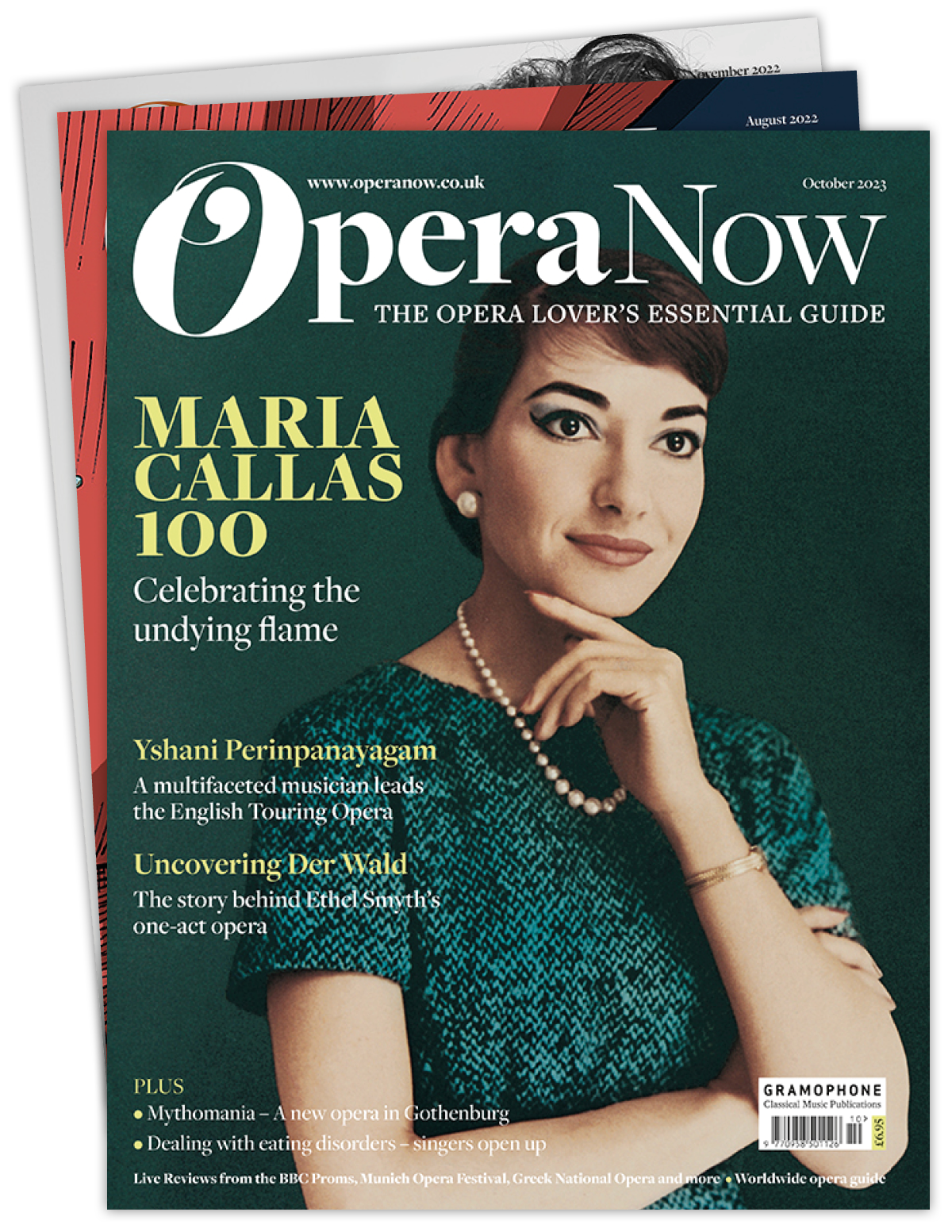

Gerald Finley as Antony and Julia Bullock as Cleopatra in John Adams's 'Antony and Cleopatra' (Photo: Karen Almond)

With its arrival on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera, Antony and Cleopatra reaches its most convincing form to date. John Adams’s newest opera has already had productions by co-commissioners San Francisco Opera (2022) and Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu (2023). As is customary with Adams, each outing has brought revisions — most conspicuously in trimming the score, a process he has continued for the Met version. The design team has remained consistent since the opera’s premiere, but this latest iteration, which the composer himself conducts, introduces further refinements to the staging, along with newly added choreography.

Antony and Cleopatra marks a striking departure from Adams’s earlier operas. For the first time, he crafted the libretto himself, distilling Shakespeare’s expansive late tragedy while incorporating material from other ancient Roman sources, including a prophetic passage from Virgil. Most significantly, the musical dramaturgy diverges from patterns familiar to long-time Adams followers: gone are the grand choral tableaux and lyrical set-pieces, replaced by a more propulsive dramatic arc – dense with text and, in the lengthy first act, driven by restless narrative momentum.

Despite Adams’s status as the most frequently performed living composer at the Met – this is the fifth of his stage works to enter the company’s repertoire – there is nothing populist about Antony and Cleopatra. He has created a work of uneasy truths and flickering beauty, a tragedy in which emotion and image, passion and ruin, are tightly intertwined. Adams demands close attention and rewards it not with obvious operatic tropes, but with a cumulative and subtle psychological impact.

The opera condenses one of Shakespeare’s most sophisticated and psychologically intricate tragedies into a two-act structure that pivots around a triangular dynamic: the titular lovers, Antony and Cleopatra, consumed by their desire and the limits the world sets on it, and Caesar (as the future Emperor Augustus is called throughout), consumed by an unrelenting lust for power. As the opera’s central couple, Julia Bullock and Gerald Finley channel a fierce, thrilling chemistry that not only electrifies their scenes together but also informs the unfolding of their characters when they are apart.

While their story echoes the star-crossed lovers in its tragic miscommunications — including the false report of Cleopatra’s death and their mutual suicides – this is no Romeo and Juliet. Their relationship has a feral edge: not merely passionate but volatile, shot through with suspicion, jealousy and an impulse for destruction — of one another, of themselves and of the imperial worlds they are expected to uphold.

Julia Bullock as Cleopatra and Gerald Finley as Antony in John Adams's 'Antony and Cleopatra' (Photo: Karen Almond)

A sense of uncontrollable rage courses through the opera. Cleopatra torments the attendant who brings news of Antony’s marriage to Caesar’s sister, Octavia (sung by Elizabeth DeShong with muted fragility), while a humiliated Antony brutalises Caesar’s representative Agrippa (the vocally imposing Jarrett Ott) for trying to persuade Cleopatra to abandon him. Each manipulates and wounds the other. Adams withholds the consolation of a love duet, offering only the hint of one on the threshold of war: intimacy, when it surfaces, flickers through tense exchanges rather than lyrical communion.

Bullock’s piercing intelligence and expressive nuance made Cleopatra much more interesting than the clichéd seductress: a mercurial strategist who moves fluidly between artifice and raw feeling – improvisational by instinct, always recalibrating. Grounded by a dark-hued, expressive lower register, her voice similarly negotiated the sudden turns and wide leaps of Adams’s writing with emotional bite, meeting Antony’s death with a blood-curdling scream that momentarily exposes the grief beneath her calculated control. Her death scene — tautened for this version and one of the opera’s highlights – became a multifaceted Liebestod blending resistance with resignation.

Vocal stamina and psychological acumen are equally essential to depicting Antony, and Finley brought both in abundance. His voice remained commanding even as the character’s certainty fractured, and he captured Antony’s unravelling not through grand gestures but an erosion of bravado — nowhere more memorably than in his haunted monologue in the second act about the cloud shapes as a metaphor for the loss of a sense of self (‘Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish…’). Finley sang with clarity and burnished strength, charting Antony’s collapse to devastating effect.

Paul Appleby brought a cool, ruthless edge to Caesar, his usually mellifluous tenor hardened, even barbed to signal the ruler’s puritanical disgust for the lovers’ passion — and his political opportunism. His speech declaring Rome’s destiny to rule the world – more noticeably miked than the otherwise subtle amplification – harangued with icy command, magnified by the forceful presence of the chorus.

Bass-baritone Alfred Walker was a standout, lending weight and gravitas to Antony’s lieutenant Enobarbus, who supplies much of the context for Cleopatra’s allure. Taylor Raven was a canny and loyal Charmian, navigating the shifting tides of court life with finesse.

Director Elkhanah Pulitzer’s smart, time-collapsing production overlays ancient imagery with the visual codes of golden age Hollywood and 1930s mass media documenting the emergence of the fascist propaganda machine with grainy projections designed by Bill Morrison and Constance Hoffman’s period-sliding costumes. Mimi Lien’s streamlined, mobile, set makes the stage a shape-shifting zone of power, illusion and decay. New to the Met’s production is Annie-B Parson’s stylised choreography, which reinforce the sense of historical patterns in eternal repetition.

From the pit, Adams drew a performance of urgent clarity from the Met Orchestra, shaping the score’s nervous polyrhythms and tracing its sinuous, slithering gestures with precision. The musicians adapted to his language with fluency, from darting winds and shimmering cimbalom to dusky, fractured brass fanfares, creating a sound world of coiled tension. In Cleopatra’s death scene, it finally comes to rest not in resolution, but in the gradual slowing of the pulse of desire itself.

Until 7 June metopera.org