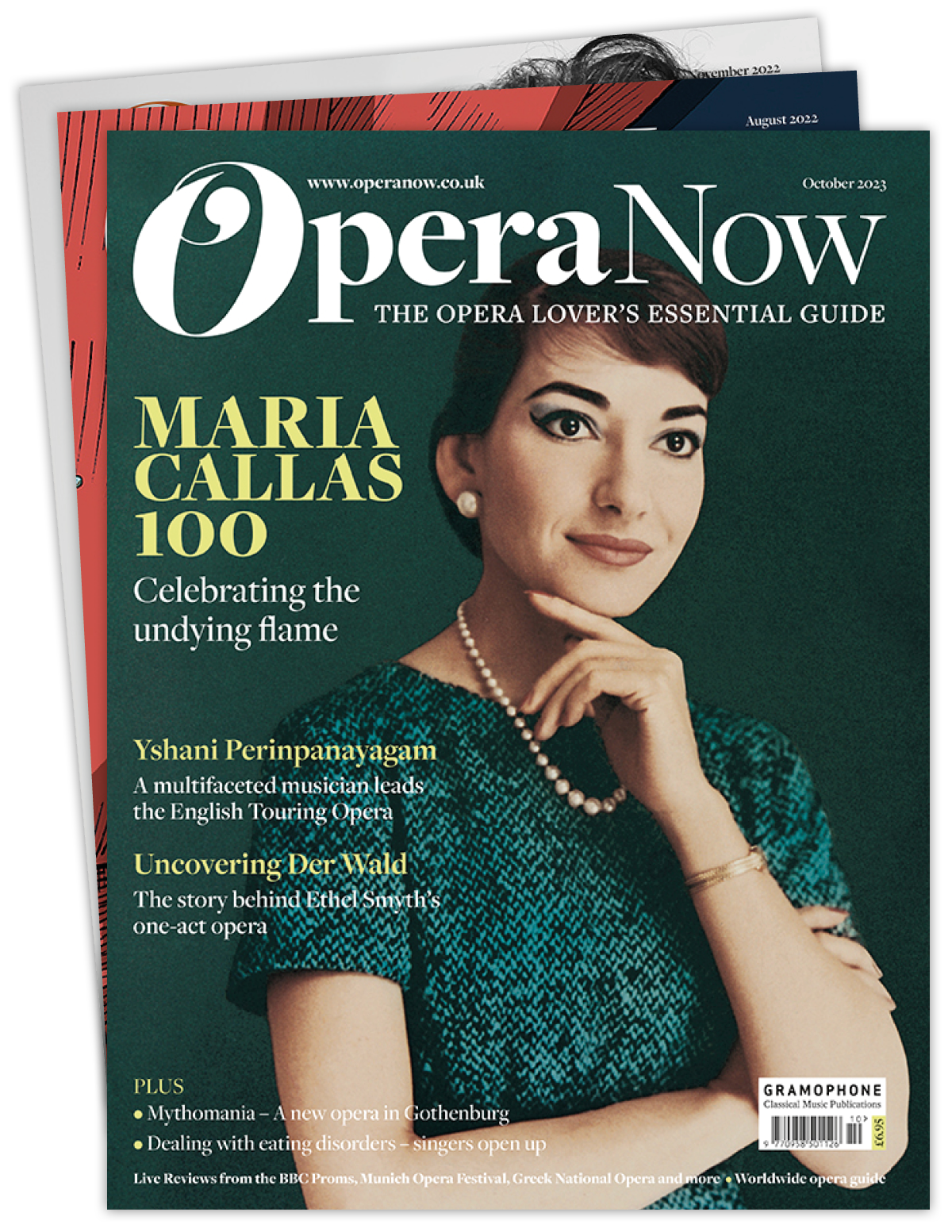

Avner Dorman: Wahnfried at Longborough Festival Opera | Live Review

Jonathan Whiting

Monday, June 2, 2025

'The mischievous Wagner-dæmon offers biting commentary, effectively amplifying the opera’s critique of fanaticism'

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter