Wagner: Parsifal at Glyndebourne | Live Review

Gavin Dixon

Monday, May 19, 2025

Everything about this production is clearly inspired by the venue, its traditions and especially its size

⭐⭐⭐

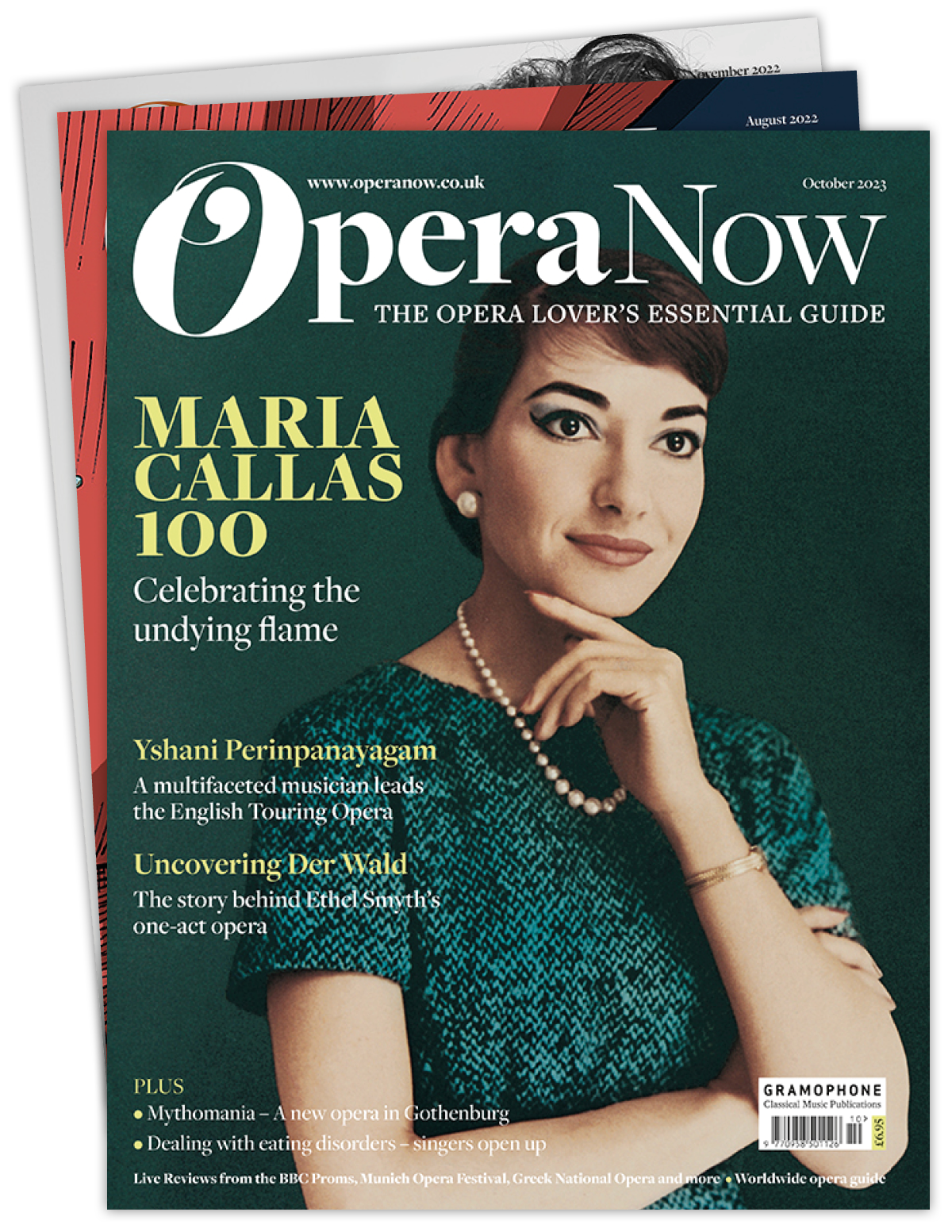

Parsifal at Glyndebourne (Photo: Richard Hubert Smith)

Glyndebourne further consolidates its status as a Wagner house with this, its first production of Parsifal, a work the company has aspired to for almost its entire history. But there is little sense of valediction in the staging from director Jetske Mijnssen, herself new to the work, and indeed to Wagner. Mijnssen presents us with multiple doppelgangers of Kundry, Amfortas and Klingsor, has Titurel roaming the stage throughout the first act, and allows Klingsor to survive the second act and to appear throughout the third, finally making peace with Amfortas as he lies on his deathbed.

All of which is to say that this is very high-concept staging. Fortunately though, and in deference to the venue and its traditions, the aesthetic is resolutely old-fashioned. Mijnssen takes Chekov as her model, and the setting (sets by Ben Baur) is a decaying mansion, with tall, columned walls and low-angled lighting (Fabrice Kebour) defused through a shuttered window stage left. The Chekovian theme inspires a reading in which Wagner’s themes of salvation and self-sacrifice take place on a personal and social scale, so many of Mijnssen’s narrative interventions are designed to play down the work’s mystical and ritualistic dimensions. Gurnemanz (John Ralyea) appears in clerical garb, but his narrations are given an earthly dimension through being acted out in mime as he sings. Two curtains, placed mid-way down the stage, open to reveal small sets for each of these flashbacks.

More disconcertingly, Titurel is present and observes throughout. John Tomlinson takes the role, and it is easy to feel sorry for Ralyea, having to perform Gurnemanz in the presence of one of the finest living exponents. Tomlinson himself is enjoying an Indian summer of minor cameos. This appearance follows an excellent comic turn as the grandfather in Turnage’s Festen at Covent Garden, and he will also be playing Dikoj in Kátá Kabanová later on in the Glyndebourne season. To emphasise the psychological dimension of the Grail Ritual, Mijnssen has it play out with just the four leads onstage, and the choir singing from the wings. That diminishes the musical experience, but the sheer claustrophobia that it induces, as Parsifal (Daniel Johansson) is repeatedly urged to participate, is compelling.

Despite the small scenery brought on for the flashback scenes, this is a single-set production, and we are back in the same setting for act 2, without any sort of castle for Klingsor. The Flower Maidens are all dressed to resemble Kundry (Kristina Stanek). Their performance is more intimidating than erotic, with some impressive blocking as they move as one to surround and overwhelm Parsifal. This acts as a prelude to Kundry’s own seduction scene, which is powerfully erotic, but in a disturbing and subversive way. Like the Grail Ritual in act one, the reinterpretation here confuses the (already tenuous) narrative but delivers an impressive dramatic climax.

Parsifal at Glyndebourne (Photo: Richard Hubert Smith)

In order for Klingsor (Ryan Speedo Green) to survive for the third act, he must only be captured, or perhaps won over, by Parsifal and the end and of the second. The result is a frustrating anti-climax, and conductor Robin Ticciati is wise to play down the musical depiction of the crumbling castle. The third act takes place around Amforas’s deathbed, and an impressive cinematic effect is employed, with the final image of the opera appearing in premonition at several points in the earlier acts. Less effective is the mute drama of the various doppelgangers, and of Klingsor, whose presence and actions rarely correlate with the words or the ritualistic drama.

Everything about this production is clearly inspired by the venue, its traditions and especially its size. So this is unapologetically small-scale Wagner, and Mijnssen uses the scale of the venue effectively to create focus and intimacy. The mostly young cast sing at a similar scale and have been well chosen for the nature of the staging. John Relyea brings an imposing tone to Gurnemanz, with the appropriate sense of authority, and only lacking the keen tonal focus that made Tomlinson the master of this role. Tomlinson himself still has the power for his small role, although much of his former tonal lustre is gone. He also has the best German of the cast. Daniel Johansson seems a very young Parsifal. His voice has an attractive burr but lacks projection. Ryan Speedo Green is suitably menacing as Klingsor, but also has the acting ability to transform the role in the last act. Kristina Stanek is cold-toned as Kundry, again perfectly fitting how the role is reimagined. She also has a powerful but colourless parlando that she brings to the seduction scene, a brilliantly effective device.

Ticciati isn’t a conductor to draw long, lyrical lines from Wagner, but he has a good feeling for dramatic build-ups, and for details of orchestration, something that the London Philharmonic, as reduced to fit the Glyndebourne pit, provides well for him. The precision and spontaneity of the LPO’s string sound compensates well for the reduced numbers, and the players clearly know how to exploit the fine acoustic to create the necessary weight.

A mixed success then, Glyndebourne’s first foray into Parsifal. Everything about the stage conception and the musical performance is geared to the venue, which clearly obliges all concerned to reimagine this large-scale work in more modest terms. The idea of presenting the piece as a psychological and social drama is effective, although as much is lost from the reimaging as is gained, and the various narrative indulgences are likely to test the patience of all but the most open-minded of Wagnerians.