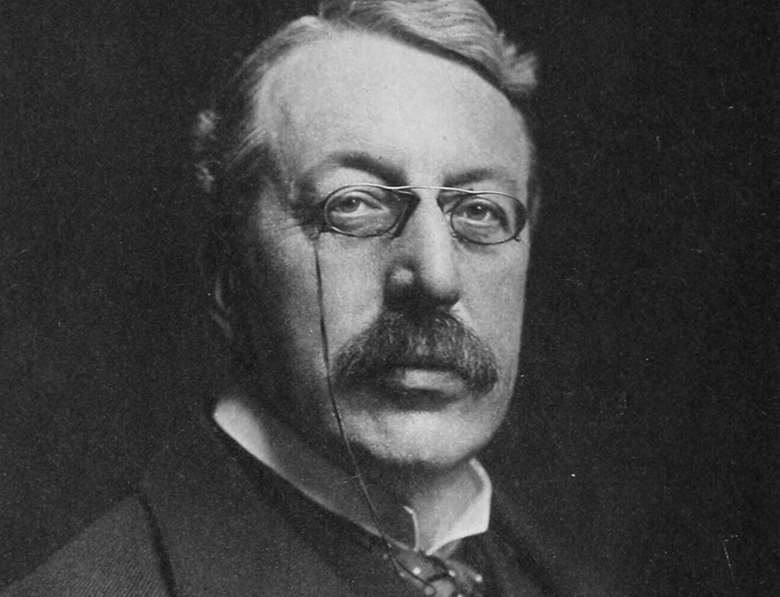

The choral music of Charles Villiers Stanford

Jeremy Dibble

Friday, February 23, 2024

As we mark the centenary of Charles Villiers Stanford’s death, Jeremy Dibble explores the choral music and the lesser-known works which have seen recent revival and recording

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Choir & Organ. Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the choir and organ worlds. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Newly-commissioned sheet music to download from our New Music series

- Unlimited access to Choir & Organ's news pages

- Monthly newsletter