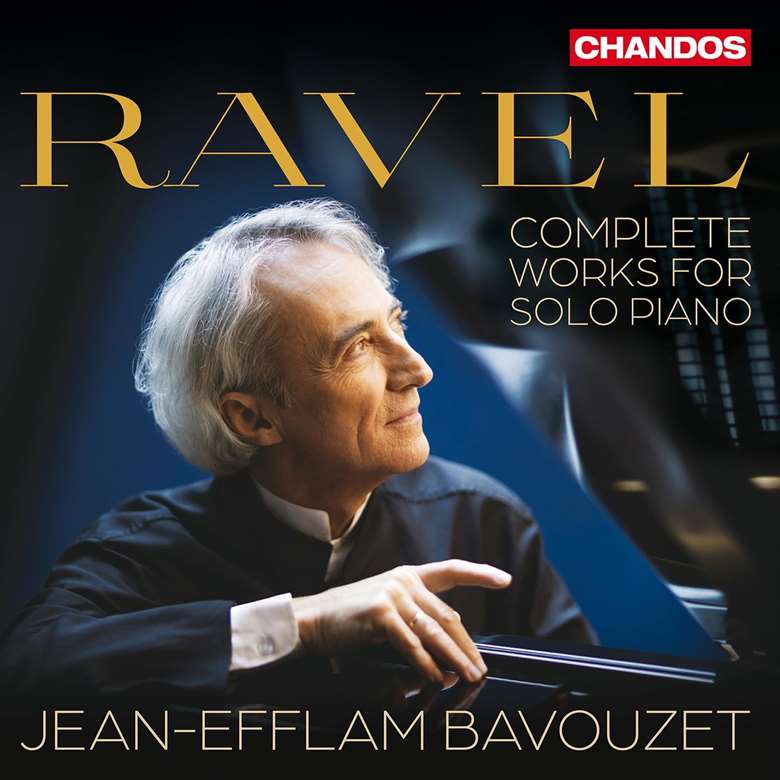

Ravel ‘Complete Works for Solo Piano’

Ateş Orga

Friday, May 23, 2025

'He tints sound like a painter might harmonise pigment'

Showcasing a 1901 Steinway D, Bavouzet’s original Ravel set appeared in 2003 (MDG). Putting the music first, benefiting from high production and engineering values, this Chandos remake (Potton Hall, Yamaha CFX concert grand, 16 of the 35 tracks marginally quicker, eight slower) is delectable and indispensable. What impacts is the ripened interpretative mastery, the disarming directness and purity of pianism. Authority and insight are lightly worn. The booklet notes include a distinguished essay from Hugh Macdonald as well as assorted Bavouzet wisdoms, with many rewards.

Anticipating facets of ‘Une barque sur l’océan’ from Miroirs, Jeux d’eau unfolds with refined pellucidness and diction, never breathless at 5’36”, Ravel’s quaver=144 rarely far away (in time-constrained acoustic/electric 78rpm days Casadesus, Cortot and Moiseiwitsch needed to be more than a minute quicker). In the various minuet cameos (five of them) and quasi-Schubertian allusions of the Valses nobles et sentimentales Bavouzet senses the dance pulse delicately, not afraid to artfully stress down-beats in the interests of rhythm and shaping, subtly blending poetry with physicality. Generating momentum, encouraging the music to flow naturally, is one of his strengths. In the half-lights of ‘Oiseaux tristes’ and ‘La vallée des cloches’ (Miroirs) he tints sound like a painter might harmonise pigment. Majestically commanding the challenges of the Gaspard de la nuit triptych, the fluidity, precision and tempo choices of ‘Ondine’ are inspiring, however obligatory Michelangeli’s quicker, icier 1959 BBC Maida Vale account. Stroked notes portées, tenutos, accents: the distant tolling B flats of ‘Le gibet’ are a masterclass in delivery and narrative. ‘Scarbo’ – faster than formerly, differently explosive – is a malignant, dwarfish apparition, here one moment, gone the next, growing ever more twisted and monstrous before vanishing in a curling wisp of vibration, a presence the more terrifying for resisting exaggeration.

There’s much to savour in Le tombeau de Couperin. The Toccata glitters, sparse pedalling lightly ‘ringing’ the texture. Elegantly placed and unfussed, Forlane dances gently, dynamics and understated distinctions of articulation catching the attention, the grace notes crushed baroque-like on the beat rather than before (respecting Ravel’s 1918 first edition instruction). La valse, omitted from the earlier intégrale, follows ‘the version for orchestra which, apart from the addition of supplementary voices, departs a little from the version for piano, notably at the very end, in the number of swirling, intensifying bars before the fatal quadruplet’. It’s a reading more nuanced than aggressed, distinctively contrasting the bacchanalian crudity and gratuitous ecstasy that’s become the vogue. The instrument as piano not orchestra, the pianist as voice of the composer.