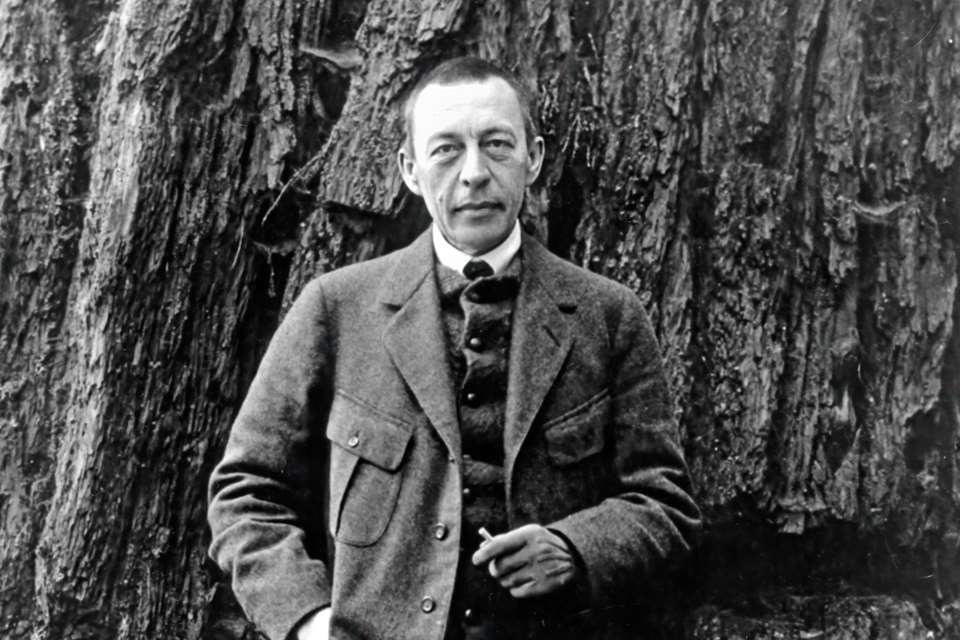

Recording the original version of Rachmaninov’s First Piano Sonata

Sunday, December 10, 2023

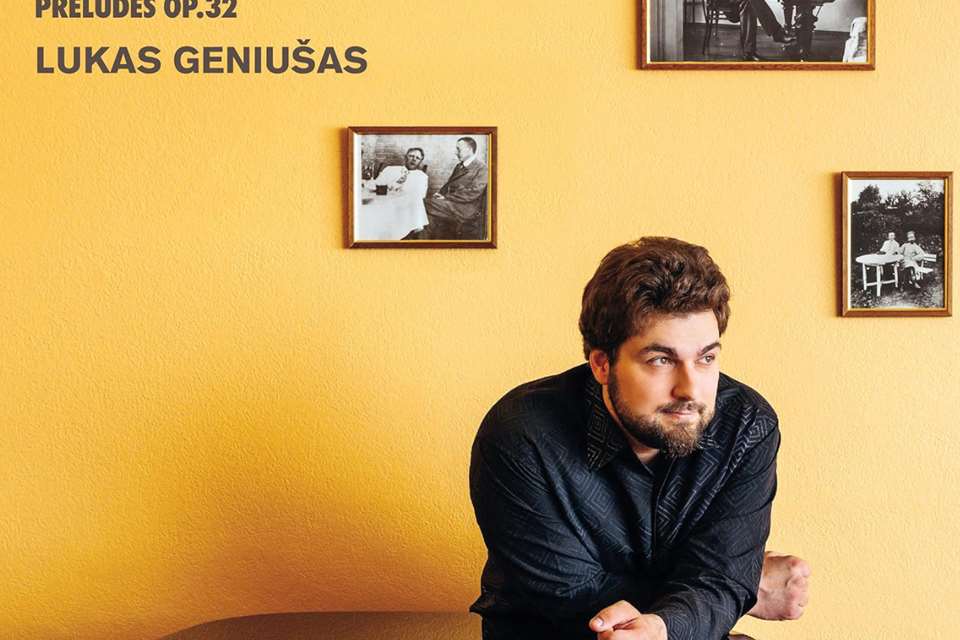

Lukas Geniušas has made the first recording of the unpublished original version of Rachmaninov’s Piano Sonata No 1. He talks to Jeremy Nicholas about exploring this absorbing work

Register now to continue reading

This article is from International Piano. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the piano world, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to International Piano's news pages

- Monthly newsletter