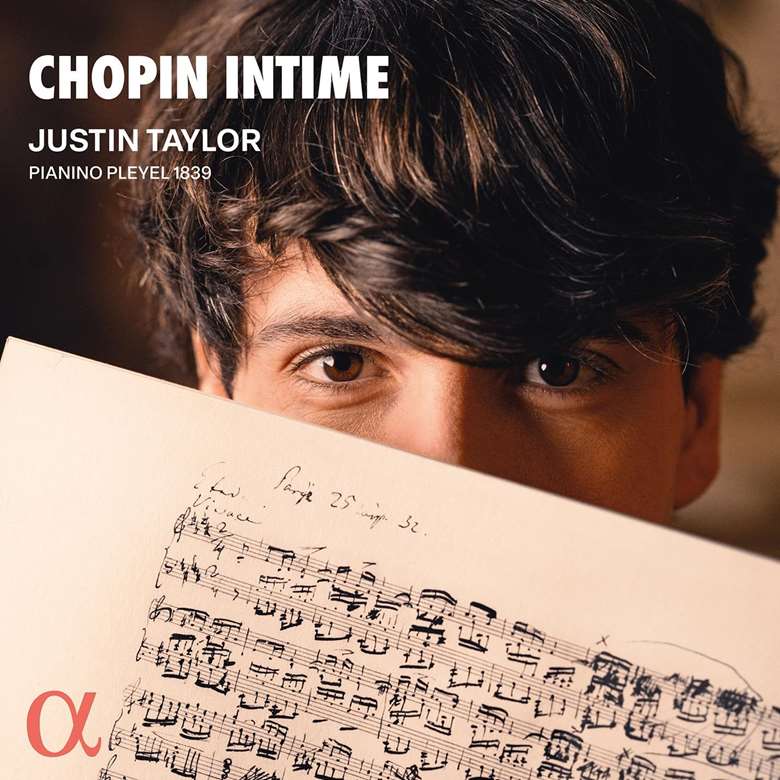

Chopin intime

Michelle Assay

Friday, May 23, 2025

'Taylor’s approach is appropriately improvisatory and spontaneous, striking a perfect balance between insight and freedom'

To clarify: this is not literally the Pleyel pianino that was delivered to Chopin in Majorca for his inauspicious stay with George Sand in 1838. It is the slightly ‘younger brother’, as the French early-keyboard rising star Justin Taylor puts it, with the same characteristics as the upright six-and-a-half-octave piano on which Chopin composed some of his Op 28 Preludes.

Taylor’s starting point for his recorded programme was naturally those Preludes (and a handful of others), in an attempt to capture an intimate ‘dialogue’ between the work and the instrument. And it is indeed a revelation to hear these works as they might have taken shape under the composer’s fingers. Taylor’s approach is appropriately improvisatory and spontaneous, striking a perfect balance between insight and freedom.

To the Preludes he has added a selection of works suitable to the instrument’s sonic universe, from Nocturnes and Études to Mazurkas and even a transcription of ‘Casta diva’ from Bellini’s Norma. This last is based on the manuscript of Chopin’s own arrangement of the orchestral part (presumably to accompany Pauline Viardot), into which Taylor has reintegrated the vocal line. The result offers a suitable halfway point for the programme and a showcase for the instrument’s colours and cantabile qualities.

Mazurkas are ideally suited to the nostalgic hues of the pianino, as is the arrangement of the second of the Polish Songs, ‘Wiosna’ (‘Spring’), a musette-like miniature in which the piano emulates a hurdy-gurdy. For a particularly sublime example of the veiled, silvery tones of the instrument, hear the harp-like passagework of the Prelude No 23, while the ‘Raindrop’ Prelude raises an important question about Chopin’s pedal indications – given the natural resonance of the instrument, the outcome is an impressionistic cloud of sound, pointing towards Debussy’s Préludes: convincing to my ears, but maybe not to everyone’s.

Taylor is not the first to attempt a recreation of Chopin’s sound world (even if the use of the upright piano makes him stand out). Alain Planès’s project ‘Chez Pleyel’ (Harmonia Mundi, 2009) on an 1836 instrument, for example, was a supposed approximate reconstruction of Chopin’s 1842 recital. But Taylor’s natural freedom and self-effacing intimacy make his a far more persuasive endeavour. This is certainly the case for the textual variants he introduces, such as the elaborate flourishes in the E flat major Nocturne, Op 9 No 2, where Taylor’s tongue-in-cheek approach comes across as far less laboured and self-conscious than Planès’s – even if both, to modern ears, give the impression of embellishing on perfection. Taylor’s left-before-right misalignments, as in the opening C sharp minor Nocturne, are subtly respectful of the formal structure, while in the middle section of the B flat minor Nocturne, Op 9 No 1, he evokes a startlingly distant oasis, showcasing the instrument’s one-string soft pedal.

The booklet includes a charming interview with Taylor and a photograph of the instrument with a rather short description. All in all, this is an important and delightful album that offers unfamiliar but convincing perspectives on familiar works.

This review originally appeared in the SUMMER 2025 issue of International Piano – Subscribe Today