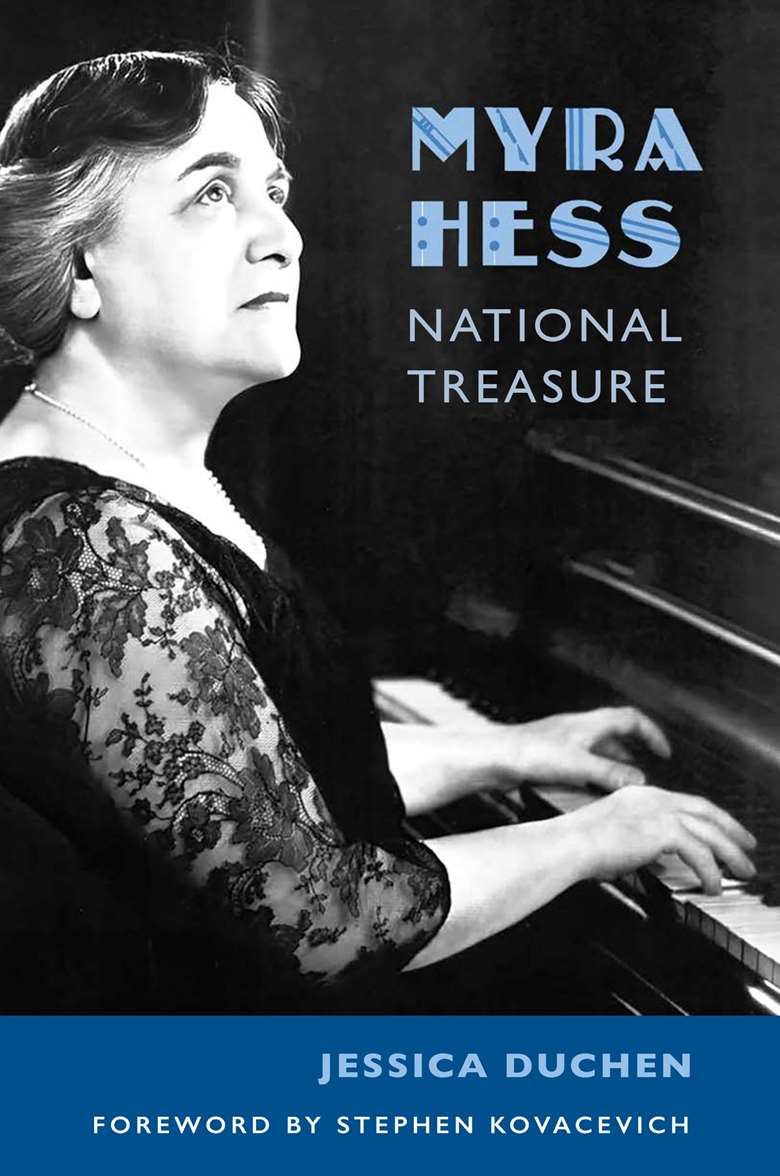

Myra Hess – National Treasure | Jessica Duchen

Jed Distler

Friday, May 23, 2025

'One can safely say that Duchen’s new volume is the definitive biography, in most respects'

Few 20th-century pianists earned both wide public recognition and critical acclaim to the extant of Myra Hess. Yet her posthumous reputation has largely been that of a figurehead and an unlikely wartime hero. And although Hess’s transcription of Bach’s Jesu, joy of man’s desiring has a secure place in the piano repertoire, knowledge of her pianistic legacy tends to be limited to scholars and specialist collectors. Just why is all this so?

One reason is that Hess was never the musical provocateur; her eminently sane, musically tasteful and vibrantly communicative performances were diametrically opposed to those of the more iconoclastic and polarising figures of her day. Another factor is that Hess recorded relatively little for a pianist of her stature, certainly when measured alongside the prolific studio outputs of slightly younger contemporaries such as Walter Gieseking and Wilhelm Kempff.

Fortunately, a number of labels have revived Hess’s commercial output, supplementing it with extant broadcast material that preserves Hess’s playing of repertoire that she did not otherwise record. And now Jessica Duchen has produced the first biography of Myra Hess since the late Marian McKenna’s Myra Hess: A Portrait (Hamilton: 1976).

One can safely say that Duchen’s new volume is the definitive biography, in most respects. Taking into account much newly uncovered documentation, Duchen offers a frank, superbly detailed, meticulously researched and thoroughly sourced portrait of Hess that is sympathetic without being gushing. As a historian, Duchen leaves nearly no stone unturned when discussing the trajectory of Hess’s life and career in the context of Britain’s classical music scene in the early to mid-20th century. Her clear, fluid and informative prose vividly draws one into Hess’s milieu, outlining her crucial studies with Tobias Matthay (essentially a substitute father) and exploring the pianist’s professional collaborations and rivalries. Naturally the morale-inspiring concerts Hess organised at the National Gallery during the Blitz form an important part of Duchen’s narrative.

It’s evident just how highly Hess was respected by her musician friends and colleagues

Perhaps the common thread that binds each of Hess’s decades before the public is that of persistence and determination in face of concert nerves, bouts of depression and the occupational hazards of touring, not to mention an unnecessary double mastectomy she underwent in 1934. Certainly Hess’s well-documented sense of humour carried her through many dark days.

It’s clearly evident from this book just how highly Hess was estimated and respected by her musician friends and colleagues. She usually reciprocated, although her letters and diaries occasionally betray cutting remarks. The few students that Hess accepted after her enforced retirement in 1962 recall her being both supportive and demanding at the same time. Beauty of tone was paramount, and rarely in her recorded performances do we hear anything ugly or forced. Whether or not one agrees with Duchen’s opinions about Hess’s recordings, the author’s immense knowledge of the piano, pianists and the piano literature is never in doubt.

The only topic Duchen broaches with kid gloves is Hess’s sexuality. It’s not clear if any man formed an intimate relationship with her, nor if she and Arnold Bax had ever acted upon their apparent mutual attraction. Anita Gunn, who looked after Hess’s quotidian needs from 1931 until her death, is consistently referred to as a ‘companion’, but nothing more. And when deflecting questions about suitors or marriage, Hess conveniently referred to the piano as her spouse. Was the piano male or female? Duchen’s ‘Selected Discography’ is reasonably comprehensive. I catch only one possible discrepancy: the 1961 BBC Schubert B flat major Sonata was issued on LP in 1980 (Recital Records RR524), although it never appeared on CD. In short, piano mavens, music lovers and history buffs alike will find Duchen’s biography most compelling. Once you start reading this book, it’ll be hard to put down.

This review originally appeared in the SUMMER 2025 issue of International Piano – Subscribe Today